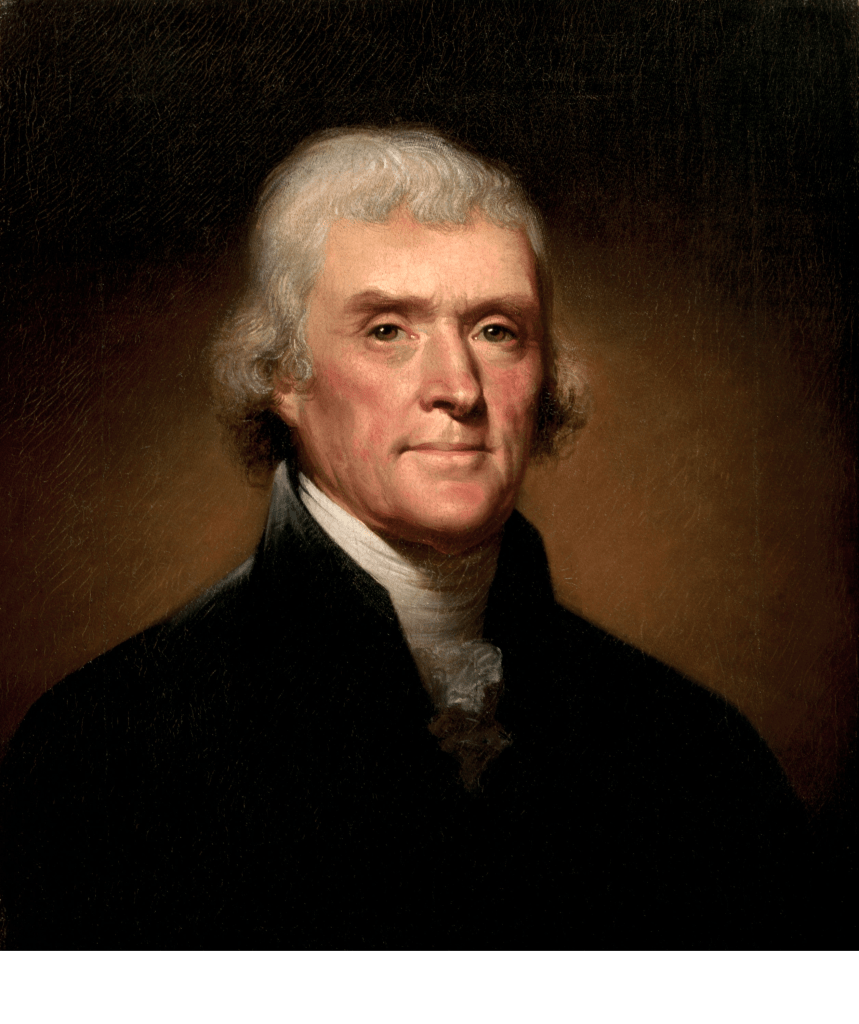

The 1800 election marked some firsts in American history. For one thing, it was the first time a president lost reelection and the smooth transfer of power in this case was an important precedent in American as well as world history. However, there was a significant complication that could have derailed the public’s will in electing Thomas Jefferson.

Background

When the Constitution was adopted in 1788, the Founding Fathers were largely of the belief that political parties were to be avoided. President George Washington, who never identified with a party, certainly thought so. However, factionalism developed from the beginning with groups we retroactively call the Pro and Anti-Administration factions. The Pro faction of course sided with George Washington and was also supportive of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and Vice President John Adams, believing in the use of federal power to grow the nation through the funding of internal improvements to grow commerce and imposing tariffs to finance such developments. The Anti faction sided with Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who idealized an agrarian society of the people and disliked the Hamiltonian system of government of protective tariffs to fund internal improvements. However, because the Constitution had it that the winner would be president and the runner-up would be vice president, it created a situation in which the president would have a political foe in the vice presidency, as happened with John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. By the 1796 election, America’s first two parties had developed in the Federalist and Republican parties. For the purposes of avoiding confusion, however, historians and others call the latter the Democratic-Republican Party, as today’s Republican Party traces its lineage to the Whigs, which traced their lineage to the Federalists. Despite the wishes of many Founders, the seeds for political parties had been planted from the very beginning. Although both Adams and Jefferson had their picks for vice president, the tickets were not official and the results made it so that under the Constitution Adams was president and Jefferson was vice president, creating a rather awkward situation in the White House. Imagine this applied to recent politics in addition to the greater role of the vice president, and you can imagine how well this would go over. Electors cast two votes each, but there was no distinction as to president and vice president in these votes.

The 1800 Election

In the 1800 election, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties officially selected president and vice president. Jefferson’s running mate was New York’s Aaron Burr and Adams’s running mate was South Carolina’s Charles C. Pinckney. In that election, the tides decisively turned against John Adams, with the Administration being unpopular due to numerous factors, including their support of greater relations with Britain, their tariffs, and the Alien and Sedition Acts, now widely regarded as an unconstitutional overreaction to fears about the influence of revolutionary France. Thomas Jefferson won with 60.6% of the vote as opposed to Adams’ 39.4%. The problem was that in the casting of electoral votes, the electors gave Jefferson and Burr 73 electoral votes, and because the electoral votes didn’t distinguish between president and vice president a Burr presidency was now possible! The Adams electors had been careful about this; his VP nominee Charles C. Pinckney received one less electoral vote than Adams, but this didn’t matter as the ticket hadn’t won. The conundrum had to be resolved by Congress, and the Federalists initially sought to make life difficult for Jefferson by voting for Burr and producing a stalemate, resulting in 35 ballots without a winner. Because state delegations were what mattered in the voting for president, this had the result of giving Delaware’s single representative, the staunchly Federalist James A. Bayard, the same power as the considerably more populous Democratic-Republican state of Virginia in determining the president. Burr, ever ambitious and far from the most ethical politician the US has ever had, was during this time accused of campaigning for himself being president as he did not rule himself out as a candidate for president. As a consequence, Burr would be completely frozen out of the Jefferson Administration’s inner circle. However, Alexander Hamilton realized that Jefferson was the preferable president. He didn’t like the idea of Burr being an instrument of the Federalists throughout his career. In 1804, Hamilton’s opinion on Burr reflected his views on him in 1801, asking, “Is he to be used by the Federalists, or is he a two-edged sword, that must not be drawn?” (Thomas Jefferson Monticello) He managed to convince some Federalists to switch their votes to Jefferson, and on the 36th ballot, Delaware’s Bayard cast his vote for Jefferson, thus producing the intended outcome of the people. An election being decided in the House of Representatives is, to say the least, not ideal as Americans would find out in 1824 (the election of the alleged “corrupt bargain”) and 1876, the only time in which a presidential candidate lost who got the majority, as opposed to the plurality, of the popular vote. Thus, Jefferson and his party proposed the 12th Amendment to the Constitution regarding the elections of the president and vice president. This amendment distinguished electoral votes for president and vice president, held whoever should have the greatest number of votes for vice president would be the vice president, and prohibited electors from a state for voting for more than one candidate from their state. The latter has had some relevance in decisions surrounding presidents; in 2000, Dick Cheney had to legally change his residence from Texas to Wyoming to still be Bush’s running mate, and this issue certainly factored in Trump declining to pick Senator Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) as his running mate this year. In a close election year, it is best not to risk loss because Florida’s electors can’t vote for the ticket if there are two Florida residents. The Federalist Party strongly opposed this proposal, as they saw it as a way to benefit Jefferson and his party and to further reduce their influence in politics. Senator Samuel White of Delaware argued that “we have not given it a fair experiment,” that “we should be cautious how we touch it”, and cautioned that the measure had potential to increase corruption, holding that the result would be to “more than double the inducement to those candidates, and their friends, to tamper with the Electors, to exercise intrigue, bribery, and corruption…” (Alder).

However, the Federalist Party was quite weak in representation and the Senate voted for the amendment on December 2, 1803, by a vote of 21-10, with all Federalists opposing and one Democratic-Republican joining them. On December 8, 1803, the House voted to ratify the amendment 84-42, or with 2/3’s of the vote. All Federalists and five Democratic-Republicans voted against, but the Jeffersonian majority was strong enough to ratify. Among the opponents was future President John Quincy Adams.

The 12th Amendment, it is true, did serve Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party, but it also adjusted to the reality of the existence of political parties, which with 20/20 hindsight just seems inevitable. That being said, Federalists were understandably self-interested in their opposition to the 12th Amendment, trying to stave off their long-term decline. The 1804 election turned out to be a cakewalk for the popular Jefferson, who had a new running mate in New York’s George Clinton and won in a massive landslide against South Carolina’s Charles C. Pinckney, who only won Connecticut and the staunchly Federalist outpost of Delaware. The Federalist Party would gradually die out, but it would ironically technically outlast the Democratic-Republican Party. The Federalist Party was finally dissolved around 1828 while the Democratic-Republican Party fell victim to its own success as the party’s tent had become far too big and it was split over the candidacy of the populistic General Andrew Jackson, dissolving around 1825. That partisan politics didn’t end with the “Era of Good Feelings” that characterized James Monroe’s administration should be demonstrative that the “end of history” will not come without the end of humanity itself.

References

Alder, C. (2016, March 3). A Far Superior Method – the Original Electoral College. In Search of the American Constitutional Paradigm.

Retrieved from

https://www.freedomformula.us/articles/a-far-superior-method/

Election of 1804. Thomas Jefferson Monticello.

Retrieved from

https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/election-1804/

The Twelfth Amendment. National Constitution Center.

Retrieved from

https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/amendments/amendment-xii/interpretations/171

To Adopt a Resolution, Reported by the Committee, Amending the Constitution. (P. 209-210). Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/8-1/s16

To Concur in the Senate Resolution to Submit for Approval to the Legislatures of the States, an Amendment to the Constitution Regulating the Election of the President and Vice President. (Speaker Voting in the Affirmative). Govtrack.

Retrieved from