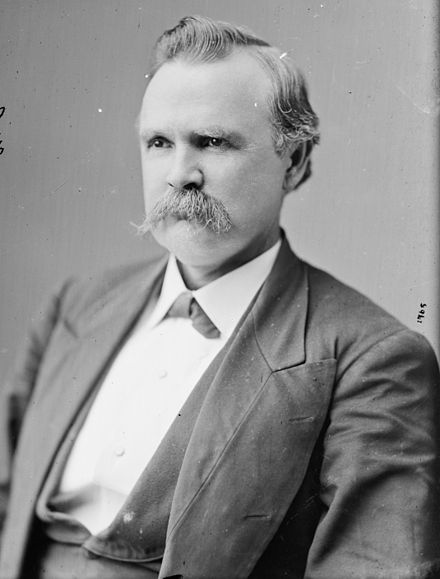

The role of Confederates in American political life after the War of the Rebellion is truly remarkable, even if their influence could never translate to being elected to the presidency or vice presidency. One of the more prominent figures in postwar America was Roger Quarles Mills (1832-1911) of Texas.

Early Political Life

As a young man, Mills was an attorney by profession in Corsicana and identified as a Whig, which is strange when you consider his stance on trade in his time in Congress. However, the dissolution of the Whig Party due to both to their devastating 1852 presidential election loss and most finally the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 had him move into the American (“Know Nothing”) Party, which was common for Southern Whigs. Mills was as a Texas politician a defender of slavery and shifted into the Democratic Party in the late 1850s as the Republican Party overtook the American Party as the core opposition to the Democrats. Even before the outcome of the 1860 election he was supporting secession over the issue of slavery. That year, he voted for Democrat John Cabell Breckinridge, but Breckinridge’s support was largely confined to the South. After this loss, Mills solidly supported secession, and this position was highly popular in Texas including Navarro County, which included Corsicana. 94% of the people who voted in Navarro County’s public referendum on secession were in support (Putman). With Texas’s departure from the Union, he left with it, serving as an officer in the Confederate Army, participating in numerous battles and rising to the rank of colonel.

During Reconstruction, Mills coordinated the activities of Texas’s KKK, but as a very loosely organized group, he may have had no direct hand in its violence. As historian Christopher Long (2021) notes, “Members of every social stratum belonged to the Klan, though the more respectable elite usually shied away from acts of violence”. In 1869, Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest ordered the disbanding of the Klan, but the Klan continued into the early 1870s.

Although the 1872-1873 elections were a triumph for Grant and the Republicans, this was not the case in Texas. In 1873, Republican Governor Edmund Davis was seeking reelection and in Corsicana a big barbeque dinner was held with a politically and racially mixed audience with black policemen part of the governor’s entourage he delivered a speech defending his policies and advocating for his reelection. Stepping up to retort was Mills. Researcher Wyvonne Putnam (1988) wrote on the impact of the speech, “Paying no attention to the Negro police he broke into one of those extemporaneous speeches so typical of him when roused. He lambasted Davis’ administration up one side and down the other. Especially did he denounce Davis’ use of the Negro police. The crowd was taken off its feet by his oratory, and when he sat down they cheered long and loud. The Negroes, who as a race always know a strong man when they see one, were not a whit behind the whites in the applause. So taken back was Davis by the demonstration that he did not stay to partake of the barbecue dinner, but got in his buggy and headed for Austin. Largely on the strength of this episode Mills was elected to Congress”.

As a member of Congress, Mills was a loud and proud Democrat, and embraced the label of “free trader”, a label that even many Democrats shied away from in the late 19th century. He supported inflationary currency through free coinage of silver as did many Texans of the time. However, this didn’t mean that Mills always was voting the way his constituents wanted him to. He was highly principled and was an unwavering opponent of Prohibition, a position gaining popularity in Texas in the 1880s. Mills regarded many of its proponents as hypocrites, and in 1887, he delivered a speech condemning such a proposal, “Prohibition was introduced as a fraud; it has been nursed as a fraud. It is wrapped in the livery of Heaven, but it comes to serve the devil. It comes to regulate by law our appetites and our daily lives. It comes to tear down liberty and build up fanaticism, hypocrisy, and intolerance. It comes to confiscate by legislative decree the property of many of our fellow citizens. It comes to send spies, detectives, and informers into our homes; to have us arrested and carried before courts and condemned to fines and imprisonments. It comes to dissipate the sunlight of happiness, peace, and prosperity in which we are now living and to fill our land with alienations, estrangements, and bitterness. It comes to bring us evil– only evil– and that continually. Let us rise in our might as one and overwhelm it with such indignation that we shall never hear of it again as long as grass grows and water runs” (Putnam). After the 1886 election, Mills would become the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, and it was there that he proposed his most famous (or infamous by Republican standards) legislation, his tariff reduction bill known as the Mills Bill, which struck at the heart of the tariff system that the Republicans so staunchly embraced. As passed by the House, this bill removed tariffs on wool, lumber, and salt and overall reduced rates by an average of 7%. Although justified as a necessary measure to reduce the surplus in the treasury (which was a problem at the time!), Republican opponents feared that this measure would constitute the first step towards the dismantling of the tariff system altogether (Ann Arbor Register). They didn’t have to fear that measure becoming law in that Congress though, as the bill was DOA in the Republican Senate. It was quite useful to Republicans, however, as a campaign issue, and they even mentioned it in the 1888 party platform, “We denounce the Mills bill as destructive to the general business, the labor and the farming interests of the country, and we heartily indorse the consistent and patriotic action of the Republican Representatives in Congress in opposing its passage.” Mills campaigned across the country for his bill, but Cleveland narrowly lost reelection and for the first time since 1872 Republicans won united government.

Mills for Speaker of the House

Democratic control of the House had had an interruption after the 1888 election but returned with a vengeance in the 1890 midterms, and Mills threw his hat into the ring to be the next House speaker. Although initially he commanded high support and even received enough pledges to vote for him sufficient for him to win, he proved overly principled in his refusal to promise individual Democrats placement in powerful positions in exchange for their votes. Another factor was that Mills had a temper and lost it often enough to give his fellow Democrats pause. On the final ballot 15 representatives defected and he lost to Charles Crisp of Georgia. Although embittered that he didn’t get to be speaker, the resignation of Senator John H. Reagan got him elected to the Senate the following year.

Senator Mills and Retirement

As a senator, Mills largely voted the Democratic line and passionately took up the cause of Cuban independence from Spain and was an opponent of the American form of imperialism, opposing the annexation of Hawaii in 1897. However, it was an act of loyalty to President Cleveland that harmed him in Texas, when he voted for the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893, contrary to his past free coinage of silver advocacy. Indeed, Cleveland’s signing this law was considered a massive betrayal by many rank-and-file Democrats, who abandoned Cleveland in 1896 in favor of free silverite William Jennings Bryan. By 1899, a coalition had formed against him with House Minority Leader Joseph Weldon Bailey (D-Tex.) and Governor James Hogg as key actors, which resulted in him not running for another term (Putnam). His DW-Nominate score, accounting for his House and Senate career, was a -0.471.

Mills retired from politics after and only became wealthy after oil was discovered on his property, which permitted him to live his last years in comfort. Four years after his wife died, Mills passed on September 2, 1911.

References

Barr, A. (2016, July 2). Mills, Roger Quarles. Texas State Historical Association.

Retrieved from

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/mills-roger-quarles

Bridges, K. (2022, July 17). Bridges: Political stances regularly derailed Mills’career. Amarillo Globe-News.

Mills, Roger Quarles. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/6531/roger-quarles-mills

Putman, W. (1988). Roger Q. Mills of Corsicana, Navarro County, Texas. The Navarro County Scroll, XXI.

Retrieved from

https://txnavarr.genealogyvillage.com/biographies/m/mills_roger_quarrls.htm

Long, C. (2021, May 28). Ku Klux Klan. Texas State Historical Association.

Retrieved from

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/ku-klux-klan

Objections to the Mills Bill. (1888, July 26). Ann Arbor Register.

Retrieved from

https://aadl.org/node/500499

Republican Party Platform of 1888. American Presidency Project.

Retrieved from

https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/republican-party-platform-1888

1. Am I understanding this correctly? Mills denounced Gov. Davis for using black police, and the blacks who were present at the meeting <i>applauded</i> Mills for that? With all due respect to Wyonne Putman, I beg leave to doubt this.

2. Gov. Davis left the meeting <i>without getting any barbecue</i>? If you ask me, anyone who’d do that deserved to lose!

This is speculation on my part, but here it goes. Blacks in the audience thought it a good idea to applaud the man most likely to be a political power as a way to aid their position in Texas’ future, despite his denouncing of Governor Davis for using black police. And yeah, not a good look for Governor Davis to not partake in barbecue, especially since he was, unlike many Republican Reconstruction politicians, born in the South!