In 1884, Grover Cleveland was elected president. He was the first Democrat since 1856 to win a presidential election, and part of his platform was honesty and integrity in government, indeed his slogan was “A Public Office Is a Public Trust” (Williams). His ethical stands indeed motivated a number of Republicans known colloquially as “mugwumps”, to vote for him or at least refuse to back Republican nominee James G. Blaine. As part of his administration, Cleveland brought some former Confederates to the cabinet, and one of them was his attorney general, former Senator Augustus H. Garland of Arkansas. He was not aware that by picking him, he opened the door to his administration possibly being caught up in a scandal; in 1883, Garland had accepted $500,000 of nearly worthless shares in the Pan-Electric Company. This was a Tennessee-based company that formed regional telephone companies and used technology developed by J. Harris Rogers, chief electrician of the Washington Capitol Building. This company was a competitor to Bell Telephone, which filed suit against the company claiming patent infringement given the many, many similarities of Rogers’ designs to Bell products. Senator Isham G. Harris of Tennesse was a friend of Rogers’ father, and he had helped them form the Pan-Electric Company in exchange for having authority to add partners to the venture (Hudspeth). A number of Tennessee politicians got in on this company along with Harris, including Congressmen J.D.C. Atkins and Casey Young. The company was nominally headed by Joseph E. Johnston, a former Confederate general and one-time Congressman from Virginia, with an initial estimated value of $5 million based on what the directors thought Rogers’ patents were worth (Hudspeth). Johnston himself would get a position in the Cleveland Administration as U.S. railroad commissioner.

Given that the Cleveland Administration on its face was seen as friendly to their interests, Pan-Electric got U.S. District Attorney for Tennessee Henry W. McCorry in 1885 to request that Garland file suit to invalidate the Bell Telephone Company patent, claiming that Interior Department employees were unduly favorable to Alexander Graham Bell. Indeed, for the Pan-Electric Company stock to have had any significant value the Bell patent would have had to be invalidated (Williams). Had the invalidation suit been successful, Garland would have made millions. He refused to do so and went on a hunting trip, which his critics saw as convenient given what would happen next: acting Solicitor General John Goode, another Southern politician formerly of the Confederacy, filed the suit in the meantime. Critics leapt on this and discovered that Garland owned a tenth of the shares distributed by the company (Williams). Indeed, Garland himself had been on the original board of directors for the company and had been an attorney for them. Once President Cleveland got word, he reprimanded Goode for not going through the proper channel, which was Interior Secretary Lucius Q.C. Lamar. Goode’s decision was revoked and submitted for review by Lamar. He had no ties to the company but when he approved the lawsuit, the press went after Garland for his shares and a Congressional investigation was launched.

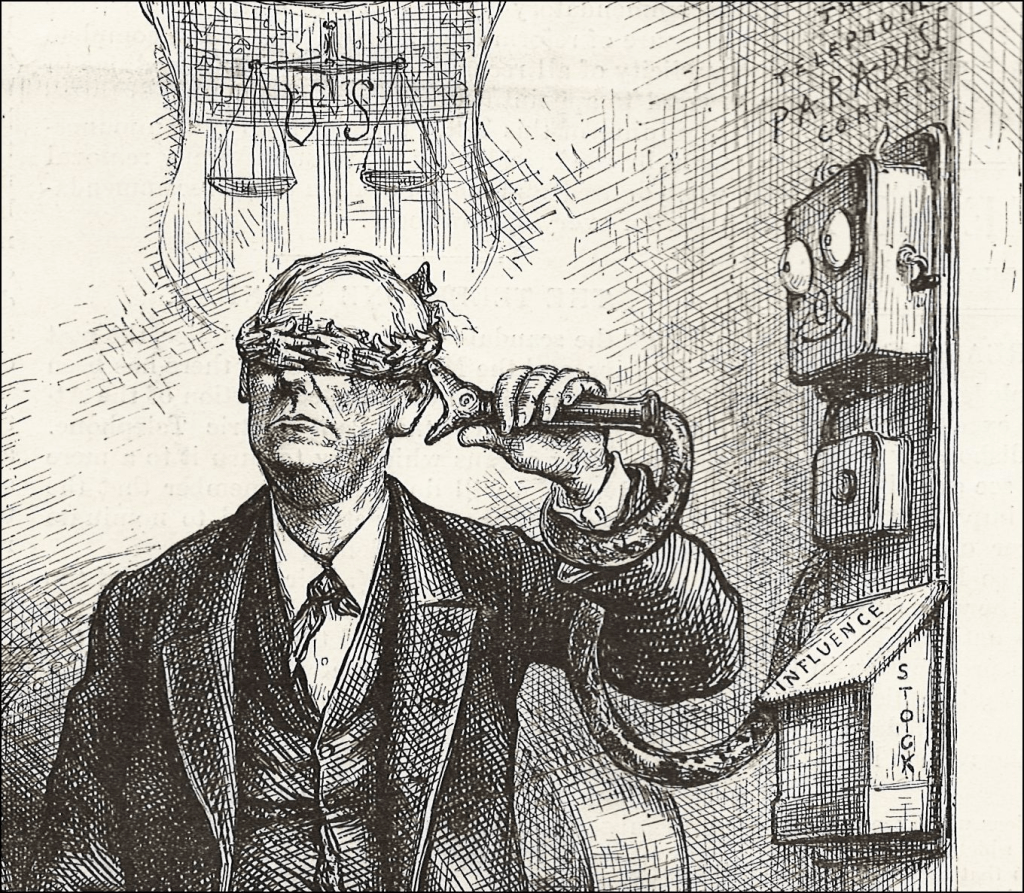

Cartoon Lampooning Augustus Garland

The Evidence to Invalidate?

The grounds that Pan-Electric and its friends used to try and invalidate the Bell patent were that it was overly generic and had been obtained fraudulently (Hudspeth, 40). There was also the allegation that people in the Interior Department of the previous administration had been biased to Bell. On February 14, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell had filed for a patent while another inventor, Elisha Gray, had filed a caveat that he would file a patent for the same invention within three months, thus suspending Bell’s patent, but Bell was awarded the patent. Legal proceedings followed and included in the evidence against Bell was an April 8, 1886 affidavit from Zenas F. Wilber, a patent examiner in the U.S. Patent Office. He attested to being an alcoholic who owed money to Bell’s patent attorney Marcellus Bailey, a fellow Union veteran. Wilber also held that he had too hastily ended the suspension of Bell’s patent based on him having paid a fee first, thus denying Gray an opportunity to challenge Bell’s patent. He also alleged that he was afterwards paid $100 to show Bell Gray’s caveat (The Washington Post). Thus, the allegation was that Bell stole Gray’s invention. These details were not in previous affidavits filed by him, and he claimed that a previous affidavit that he signed that contradicted this one was done at the behest of the Bell Company. Wilber held that he was duped into signing it while drunk and depressed before Bell attorney Thomas W. Swan (Evenson, 168). However, the April 8, 1886 affidavit was at the behest of the Pan-Electric Company. Additionally, Swan served as a witness (Evenson, 171). Wilber’s affidavits thus fell apart under scrutiny.

Result

Puck Cartoon showing Senator Harris, Attorney General Garland, and Johnston all caught up in the scandal.

Garland testified before Congress on April 19, 1886, denying that he had used his influence to benefit the Pan-Electric Company. The House, which was majority Democratic at the time, issued a majority report that exonerated Garland, Lamar, and others involved in the affair while the Republican minority report charged that Garland and Goode had deliberately engaged in a scheme to enrich themselves (Williams). Goode had been an appointment as acting Solicitor General, however, and the Republican Senate rejected his nomination. In November 1886, Judge Howell Edmunds Jackson, a recent Cleveland nominee, dismissed the suit against Bell, ending the scandal. Garland retained President Cleveland’s trust and he kept him on as Attorney General until the end of his term, and Jackson would be confirmed to the Supreme Court in 1893.

References

Augustus Hill Garland (1832-1899). Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Retrieved from

Garland, Augustus Hill

Evenson, A.E. (2000). The telephone patent conspiracy of 1876: the Elisha Gray – Alexander Bell controversy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Hudspeth, H.G. (2020, January 10). “One Percent Inspiration and 99 Percent Tracing Paper”: The Pan-Electric Scandal and the Making of a Circuit Court Judge, April-November 1886. Mississippi Valley State University, 39-54.

Retrieved from

https://www.ebhsoc.org/journal/index.php/ebhs/article/download/154/135/

Mr. Wilber “Confesses”. (1886, May 22). The Washington Post, p. 1

Retrieved from

Williams, R.H. (2021, February/March). Cleveland’s Attorney General Tries to Get Rich Quick. American Heritage, 66 (2).

Retrieved from

https://www.americanheritage.com/clevelands-attorney-general-hopes-get-rich