In my last post, I noted that a more in-depth view of the politics of Albert Einstein was necessary, so here it is. In February 1933, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, and the brain drain was immediate. Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein and his wife had already left for the United States in December 1932, anticipating his rise to power. He played a key role in persuading other countries to take in German Jewish scientists, including Britain and Turkey. The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, took him in as a resident scholar. From a young age, he held a belief in pacifism and went as far as to renounce his German citizenship in 1896, which got him out of military service. He would regain his citizenship in the 1910s but with the rise of Hitler to power he for the second and final time renounced it. In 1940, he was admitted as an American citizen.

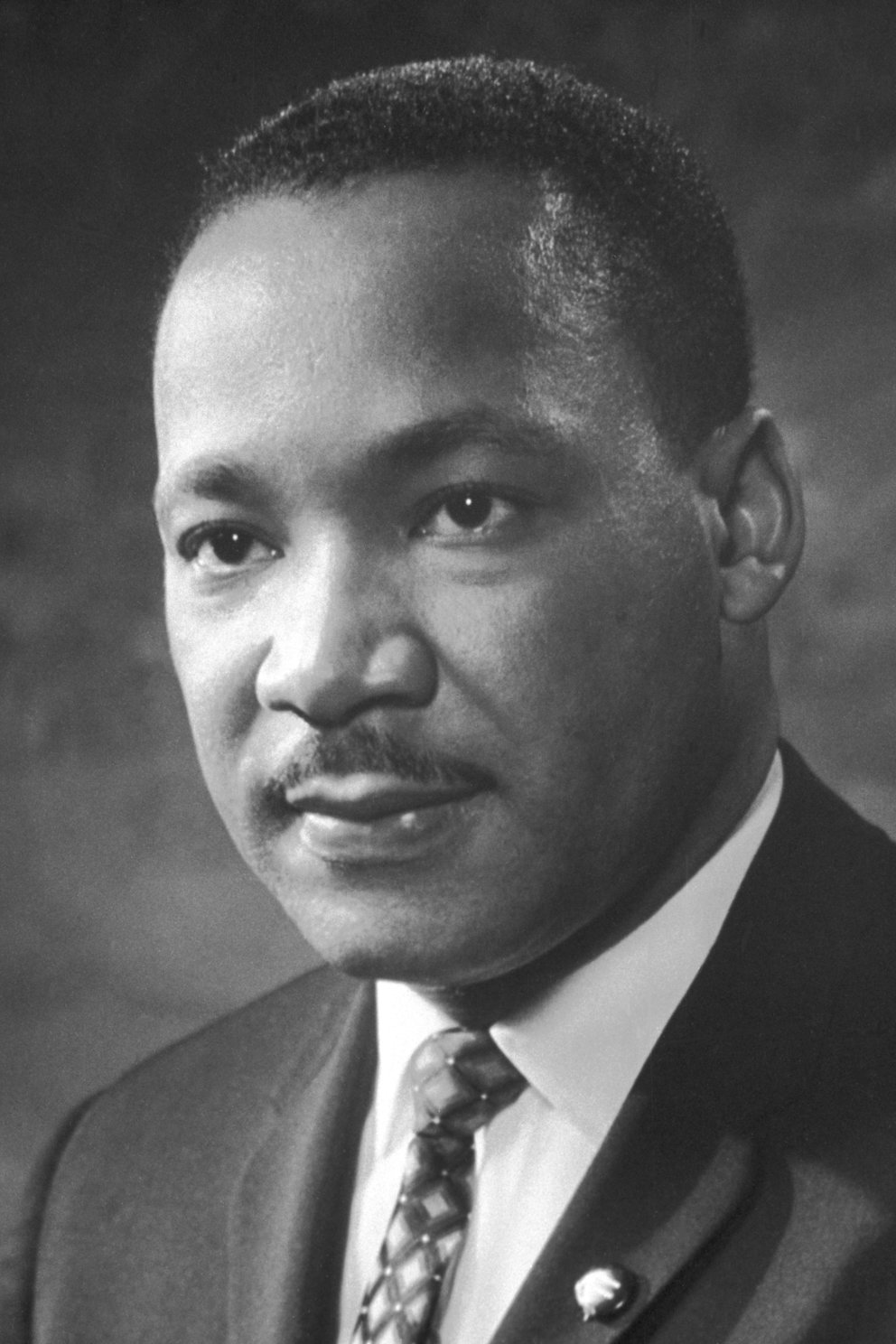

Although a new citizen, Einstein would not be quiet on his political views. He saw widespread discrimination and mistreatment of American blacks and this disturbed him profoundly. He stated on his motivations for favoring civil rights, “Being a Jew myself, perhaps I can understand and empathize with how black people feel as victims of discrimination” (Francis). Indeed, one instance in which he suffered discrimination in Germany was when Nobel Prize winner Philipp Lenard, a major anti-Semite and future Nazi, lobbied the Nobel Prize committee hard to prevent Einstein from getting the prize in physics for 1921, and so the award was delayed until the next year (Francis). He also repeatedly backed the civil rights campaigns of entertainer Paul Robeson.

Einstein and Communism

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had been highly suspicious of Albert Einstein given his politics were of the radical left, and continually looked for any indication that he was a Soviet spy. Einstein was not a spy, but his relationship with communists and communism is complicated. In 1929, he opted to criticize their methods yet praise their goals, stating, “In Lenin I honor a man, who in total sacrifice of his own person has committed his entire energy to realizing social justice. I do not find his methods advisable. One thing is certain, however: men like him are the guardians and renewers of mankind’s conscience” (Rowe & Schulmann, 412-13).

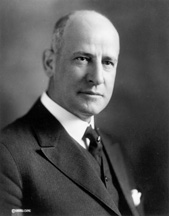

On February 13, 1950, Representative John E. Rankin (D-Miss.) delivered a speech, “Faker Einstein”, in which he lobbed numerous accusations that varied in their accuracy. I already covered his nonsense casting shade on Einstein being a scientist and his numerous prejudices, but the claims that deserve the most investigation are the ones linking him to communist front groups, especially since the CPUSA acted as an arm of the Kremlin. Such groups that he held that Einstein was involved with included the American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born, the Civil Rights Congress, National Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions, and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy. While I do not doubt that Rankin’s push against Einstein had anti-Semitic motivation, he did have connections that were cause for concern.

The American Committee for Protection of Foreign Born was an organization identified as a Communist front group by Attorney General Tom C. Clark and listed by name as subversive in the Internal Security Act of 1950. The group’s goal was to protect foreign communists from deportation and sponsors of this group included communists, socialists, and other left-wing public figures. Its chairman from 1942 to 1951 was Hugh De Lacy, a one-time member of Congress who would be revealed as a secret communist by the memoirs of CPUSA attorney John Abt.

The Civil Rights Congress was an organization headed by William L. Patterson, a prominent black communist who in 1951 presented a document before the UN with Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois titled “We Charge Genocide”, which accused the US government of complicity in genocide over failure to act against lynching and was used in Soviet propaganda against the United States. In fairness to Einstein, he also associated with non-communist civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP.

The National Council of Arts, Sciences, and Professions was a communist front group that had spawned from the pro-New Deal Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions, which Einstein sponsored along with dyed-in-the-wool communists such as Lillian Hellman, John Howard Lawson, Ring Lardner, Paul Robeson, Howard Fast, and Dalton Trumbo.

The North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy was another Communist front that provided aid through donations to the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War (Swayne, 92). Historian Peter N. Carroll (1994) regarded it as a “Popular Front organization that attracted Communists and Christians alike” (61).

That wasn’t all. As authors Karen C. Fox and Aries Keck (2004) note, “The FBI cites that Einstein was affiliated with thirty-four Communist fronts between 1937 and 1954 and was honorary chairman for three of them. While FBI agents during the Cold War probably had more expansive criteria for what constitutes a Communist front than one might today and the numbers may not have been truly that high, Einstein clearly had affiliations with organizations that in turn had affiliations with the Communist Party. However, it does not seem to have been more so than other similarly political celebrities had at the time” (61). It is also worth noting that Albert Einstein endorsed Henry Wallace of the Progressive Party, the campaign being run by the CPUSA. Given that Wallace himself was not in truth a communist (rather the USA’s #1 dupe) and that the ticket was not exclusively backed by communists, this alone cannot be considered prima facie evidence that someone is a communist. However, his connections were a cause for concern by the U.S. government and precluded any granting of a security clearance. According to an FBI report dated February 28, 1952, using information provided by U.S. Army Intelligence, “Prior to 1933, the Comintern, and other Soviet Apparats, were active in gathering intelligence information the Far East. The agents who gathered this information sent it to agents in other countries in coded telegrams. These agents then recoded the telegrams the telegrams and forwarded them to addresses in Berlin, one of which is the office of Albert Einstein….Einstein’s personal secretary turned the coded telegrams over to a special apparat man, whose duty it was to transmit them to Moscow by various means…

It was common knowledge, especially in Berlin, that Einstein sympathized with the Soviet Union to a great extent. Einstein’s Berlin staff of typists and secretaries was made up of persons who were recommended to him (at his request) by people who were close to the Klub Der Geistesarbeiter (Club of Scientists), which was a Communist cover organization. Einstein was closely associated with this club and was very friendly with several members who later became Soviet agents. Klaus Fuchs, who was associated with the club as a student in the early 1930s, was jailed in England for giving atomic bomb information to the Soviets. Einstein was also very friendly with several members of the Soviet Embassy in Berlin, some of whom were later executed in Moscow in 1935 and 1937” (Romerstein & Breindel, 279). The decision to exclude him from a security clearance in July 1940 and thus the Manhattan Project was probably correct given that his associations made him a security risk.

Einstein was also good friends with historian, sociologist, and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois (whose long history of pro-communist attitudes and actions culminated in his joining the CPUSA in 1961) and entertainer Paul Robeson. Robeson was a firm Stalinist and although he publicly denied he was a communist, chairman Gus Hall announced in 1998 that Robeson had been a secret member (Radosh). In January 1953, Einstein publicly appealed for clemency for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who had been convicted of stealing nuclear secrets for the Soviets. Naturally, he was also a critic of postwar anti-communism, especially the sort practiced by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Einstein cannot be said to be a spy or even a communist, but his connections with front groups and figures are highly suggestive of fellow travelling. This being said, he was not afraid to take positions that didn’t fit with Soviet dogma and was critical of the USSR’s increasingly anti-Semitic post-war policies. His friend Robeson, by contrast, never criticized the USSR despite knowing of the evils within the regime. Former Soviet agent Louis F. Budenz perhaps got it best on Einstein when he testified that “As a matter of fact, most of the fellow travelers are Communists. There is only a very small group of the type of Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann and people of that kind who, because of their eminent positions, would certainly feel insulted to be under Communist discipline. They are fellow travelers in the sense that they sign many statements under the influence of the people around them” (U.S. Senate, 626). Although many fellow travelers were in fact communists, Einstein was not but was among many such people who influenced him. He also, consistent with his approach of free thought, criticized the USSR in a letter, writing “there seems to be complete suppression of the individual and of freedom of speech” (Isacson, 433).

Einstein additionally stood for world government in the face of atomic weapons, a stance that got pushback both in the US and the USSR. The latter initially was against the idea of siding with groups that called for non-proliferation of arms, but they later sided with such groups to influence and pressure western nations. In May 1949, Einstein’s article, “Why Socialism?” appeared in the socialist publication Monthly Review, in which he argued for a system in which “the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion” (Einstein). He believed that an economy could be feasibly scientifically planned yet expressed caution about the potential for a bureaucracy to form that would enslave the public, thus such a system would have to be one in which democracy is assured. The one regret of Einstein’s life surrounded his compromising his pacifism to halt the Nazis. As he reflected in 1954 to Linus Pauling, “I made one great mistake in my life – when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification – the danger that the Germans would make them” (Crockatt, 115). In this ironic sense, Einstein probably wished that Mississippi’s Rankin was entirely correct in that he had nothing to do with the development of the atomic bomb.

References

Carroll, P.N. (1994). The odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans in the Spanish Civil War. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Crockatt, R. (2016). Einstein and Twentieth-century politics: ‘a salutary moral influence’. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Einstein, A. (1949, May). Why Socialism? Monthly Review.

Retrieved from

Fourth Report of the Senate Fact-Finding Committee On Un-American Activities: Communist Front Organizations. (1948). California Senate.

Retrieved from

https://archive.org/details/reportofsenatefa00calirich/page/n1/mode/2up

Fox, K.C. & Keck, A. (2004). Einstein A to Z. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Francis, M. (2017, March 3). How Albert Einstein Used His Fame to Denounce American Racism. Smithsonian Magazine.

Retrieved from

Isacson, W. (2008). Einstein: His life and universe. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Matthews, R. (1992, June 5). Einstein’s ‘red’ links were genuine. New Scientist.

Retrieved from

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg13418241-800-einsteins-red-links-were-genuine/

Radosh, R. (2019, August 27). The Price of Self-Delusion. The American Interest.

Retrieved from

https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/08/27/the-price-of-self-delusion/

Review of the Scientific and Cultural Conference for World Peace. (1949, April 19). Committee on Un-American Activities, U.S. House of Representatives.

Retrieved from

Romerstein, H. & Breindel, E. (2000). The venona secrets: Exposing Soviet espionage and America’s traitors. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc.

Rowe, D.E. & Schulmann, R. (2013). Einstein on politics: His private thoughts and public stands on nationalism, zionism, war, peace, and the bomb. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

State Department Employee Loyalty Investigation: Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations, Part 1. U.S. Senate.

Retrieved from

Swayne, S. (2011, February 7). Orpheus in Manhattan: William Schuman and the shaping of America’s musical life. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Waldrop, M. (2017, April 18). Why the FBI Kept a 1,400-Page File on Einstein. National Geographic.

Retrieved from

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/pages/article/science-march-einstein-fbi-genius-science