It can be highly tempting for people to say that one state has “always been conservative” or “always been liberal” to explain away party switches. But the reality is that populations shift, political priorities shift, and one party’s policies can go so strongly against a certain state’s interests that their voters move to the other party, even if in the past they had supported much of what their old party stood for. This has been demonstrably true of some states even in modern day. I will present today five examples of states, not in the former Confederacy or New England, which have had considerable evolution in their status.

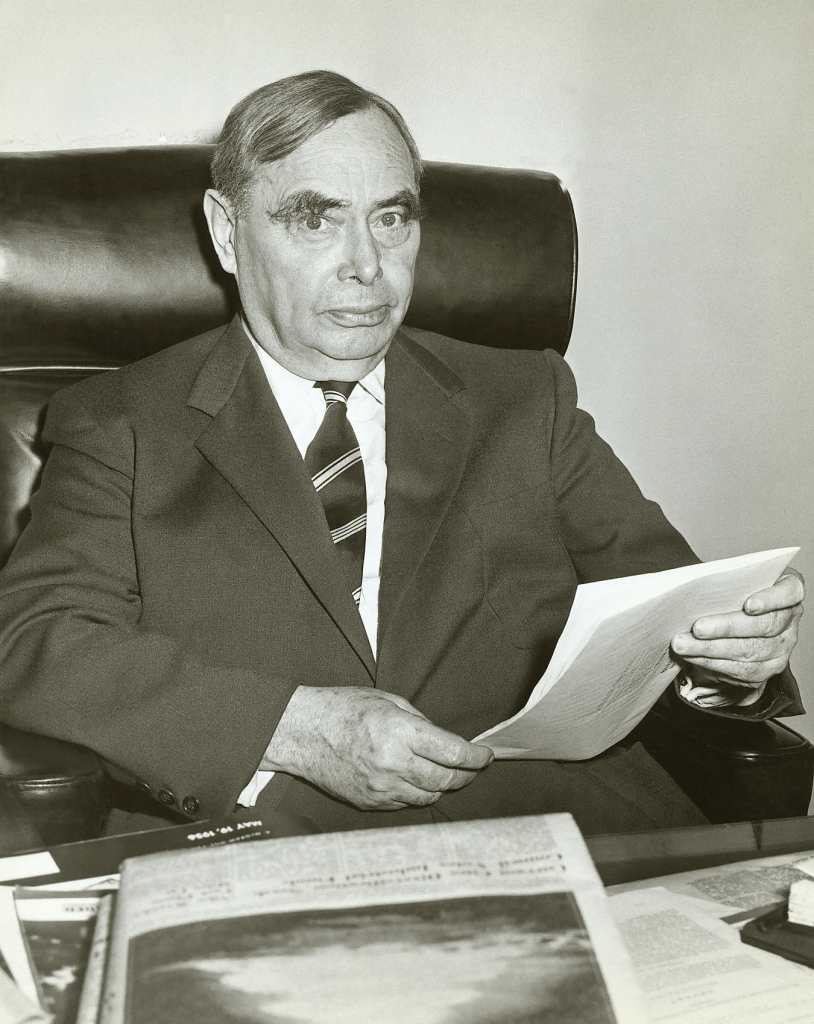

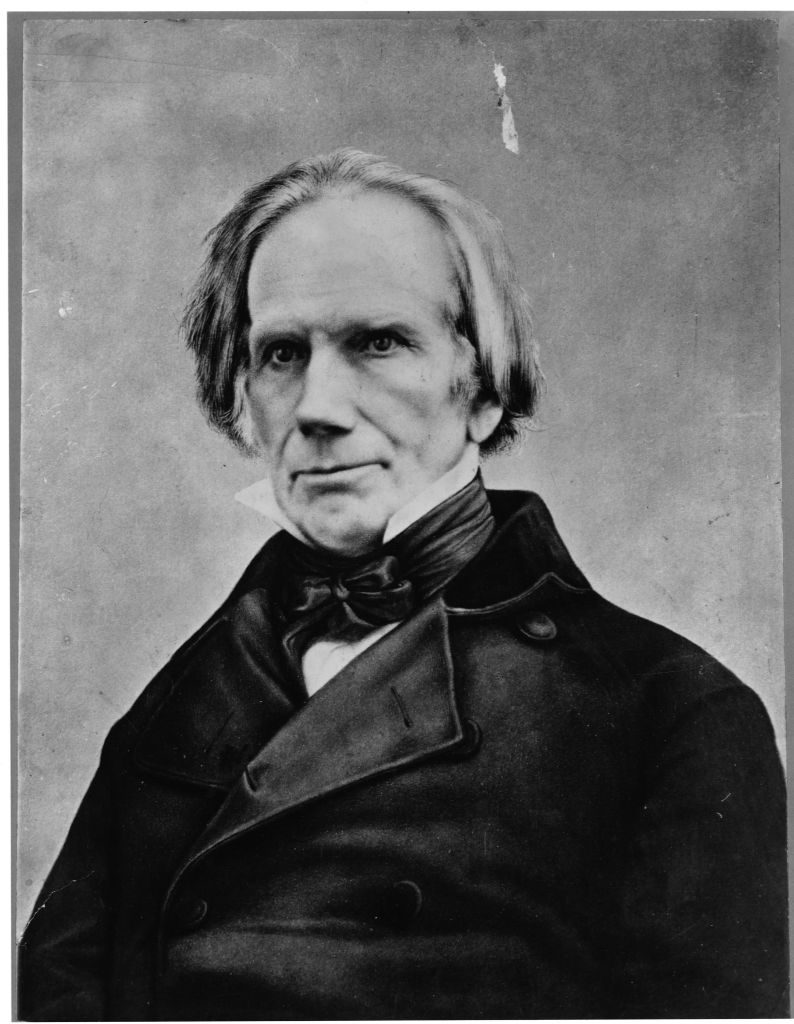

Henry Clay of Kentucky, whose state and him went from being supporters of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans to being staunchly with the Whig Party.

Delaware

Our last president was the first from America’s first state of Delaware. Since 1992, the state has voted Democratic and since 1996 it has done so by double digits save for 2004. Delaware also now has the distinction of having elected the first member of Congress to identify as trans. The state’s Democratic dominance would have been absolutely unthinkable during the time of the foundation of the Democratic Party itself.

Delaware had been one of the most loyal states to the old Federalist Party, only voting for the Democratic-Republicans in the 1820 election in which James Monroe had no substantive opposition. Delaware was also a reliable state for the Whig Party until 1852, when all but four states voted for Democrat Franklin Pierce. Normally, Delaware voters would be supportive of the economic philosophy that guided both the Federalists and the Whigs; an adherence to Alexander Hamilton’s American System. This being imposing tariffs both for protection of domestic industry and to fund internal improvements for the purpose of expanding national growth. The Whig’s successor party, the Republican Party, would embrace the same. However, Delaware was a tough state for Republicans because it was a slave state. Although slavery was not practiced by most families in the state by the start of the War of the Rebellion, many voters still defended the “peculiar institution” and the political of the power of the state lay with its defenders. During the war, its voters elected Unionist politicians to the House, but its senators were Democratic and defenders of slavery in Willard Saulsbury, James A. Bayard, and George Riddle. From 1865 to 1895 all of its governors were Democrats, and until the 1889 election all its senators Democrats. What changed in Delaware was that more blacks were becoming middle class, thus making the issue of race less salient. What’s more, a certain prominent family moved their operations to Delaware and bankrolled the state’s Republican Party in the du Ponts. Although in 1888, Delaware had voted for Democrat Grover Cleveland by nearly 12 points, an ominous signal of times ahead for the Democrats came in the next election, in which Cleveland won, but by only 1.5 points. This was an election in which incumbent Benjamin Harrison was unpopular and Cleveland scored unexpected wins in states that had consistent records of Republican voting in Illinois and Wisconsin, the former having voted Republican since 1860 and the latter having done so since its first presidential election in 1856. Delaware’s politicians, be they Democratic or Republican, had records of opposition to inflationary currency, and the economic depression as well as the Democrats shifting towards the left by picking William Jennings Bryan, a proponent of currency inflation through “free coinage of silver” (no limits on silver content in coinage), left Delaware cold. McKinley won the state by 10 points in 1896.

The 1896 election kicked off a period of Republican dominance. Until 1936, save for the 1912 three-way election, Delaware voted for the Republican candidate. Henry du Pont and his cousin Thomas were elected to the Senate during this period, and during FDR’s first term, its senators, Daniel Hastings and John Townsend, were the most consistent opponents of the New Deal in the Senate and voted against Social Security. However, FDR’s appeal even penetrated Delaware; Hastings would lose reelection in 1936 and Townsend in 1940. However, in 1948, Delaware would return to the Republican fold in voting for Thomas Dewey. The state would vary in its voting behavior through 1988, and it would go for the Democrat in the close 1960 and 1976 elections. Since 1993, Delaware has had only Democratic governors, and it has not elected a Republican to the Senate since 1994 nor to the House since 2008. A big part of the state’s shift towards the Democrats was that from 1990 to 2018, the black population of Delaware increased by 47% (Davis). Since 1964, black voter support for Republican presidential candidates has not surpassed 15%. Delaware does not look like it will turn away from the Democrats any time soon.

Iowa

Admitted to the Union in 1846, Iowa started existence as a Democratic state. In 1848, its voters preferred Michigander Lewis Cass to Whig Zachary Taylor. However, a significant minority of Iowa’s Democrats were staunchly anti-slavery and after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, these people bolted to the newly formed Republican Party. The GOP’s most prominent politician in the latter part of the 19th century and for a few years in the early 20th was Senator William B. Allison, who would be part of the Senate’s leadership during the McKinley and Roosevelt presidencies. Until 1912, Iowa would without fail vote for Republican presidential candidates and would not do so again until 1932. From 1859 until 1926, all of its senators were Republicans, and the 1926 case was because Republicans had split over their nominee, Smith W. Brookhart, who was on the party’s liberal wing. Iowa Democrats made significant headway during the 1930s, with the state even having two Democratic senators from 1937 to 1943. However, the state was moving against Roosevelt and its voters were strongly against American involvement in World War II, preferring the Republican candidate in 1940 and 1944. There was a bit of a surprise when Truman won the state in 1948, something that can be credited to his effective appeals to Midwestern farmers and painting the Republican 80th Congress as bad for their interests.

Iowa nonetheless continued its Republican voting behavior in Republican presidential elections, even though the state’s party saw significant gains in the 1970s, including both Senate seats. In 1988, Iowa delivered a bit of a surprise in its vote for Democrat Michael Dukakis. Indeed, from 1988 until Trump’s victory in the state in 2016, Iowa would be Democratic on a presidential level with the only exception being Bush’s squeaker of a win in 2004. Since 2016, however, support for Republicans has only been increasing. In 2024, Trump won the state by 13 points despite that Seltzer poll. This was the best performance a Republican candidate has had in Iowa since 1972, when Nixon won with 57%.

Kentucky

Kentucky has an even more varied history as a state than Delaware. After it was first admitted, it did, as did all the other states, vote to reelect George Washington in 1792. However, when it came to choosing between Adams and Jefferson, they chose Jefferson and kept doing so up until the foundation of the Whig Party. The Whig Party had as its central founder Kentucky’s Henry Clay, who at one time had been part of Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans but had opposed the rise of General Andrew Jackson.

Kentucky’s issue with sticking with the successor party was the same as Delaware’s: it was a slave state. It remained in the union but its voters were staunch foes of the GOP. Kentucky did not vote Republican until 1896, and did so narrowly, a product of the economic depression and Democrat William Jennings Bryan’s inflationary currency stance. Although this looked like an opening and indeed Republicans had a few successes in electing governors, the state maintained its Democratic character up until 1956, its voters having only seen fit to vote Republican in 1924 and 1928. The 1956 election was quite successful for Dwight Eisenhower and Republicans, including in Kentucky. Not only did the state vote for him, they also voted in two Republicans to the Senate in John Sherman Cooper and Thruston B. Morton. However, their brand of Republicanism was much more moderate than what we see from Kentucky’s GOP today. Republicans followed up their 1956 win with Nixon’s 1960 win of the state. From 1956 onward, Kentucky did not vote for a Democratic candidate for president unless he was from the South. The last time the state voted for the Democrat was Bill Clinton in 1996. Nonetheless, the state party remained strong, and from 1975 to 1985 both of its senators were Democrats. However, this was broken with the election of Mitch McConnell in 1984, and Democrat Wendell Ford retired in 1999. To this day, Ford is the last Democratic senator from the state. This Republican bent is not going away any time soon either; Trump scored the highest margin of victory that any Republican has in 2024, even surpassing Nixon’s 1972 performance. However, Kentucky does still elect Democratic governors, but this puts it in a similar position to Vermont, which is highly Democratic but has happily elected Republican Governor Phil Scott.

New York

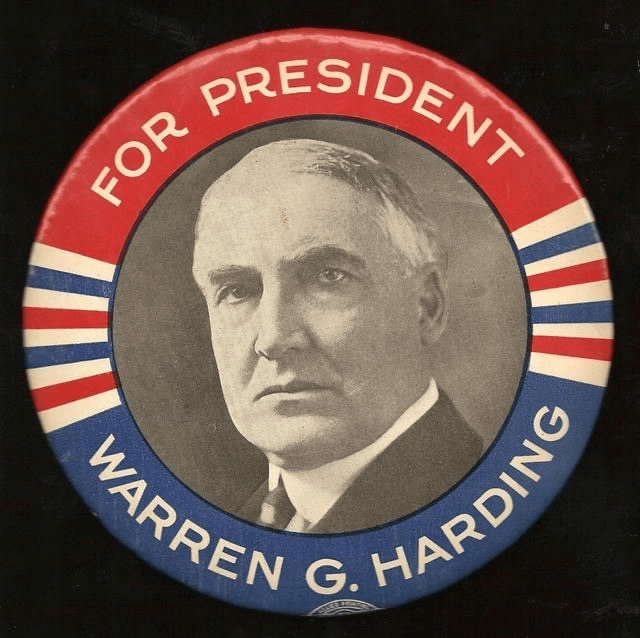

New York presents an interesting case as although recently it has voted solidly for the Democrats since 1988, it was at one time a big swing state. Indeed, New York’s vote was predictive of the winner of presidential elections until 1856, when their voters backed Republican John C. Fremont. However, this did not put them firmly in the Republican column. Indeed, Democrats had a strong presence in the state through the political organization of Tammany Hall in New York City. Republicans had a powerful machine as well in the late 1860s to early 1880s under Senator Roscoe Conkling. The electoral vote rich state became a prime target for the parties, and it resulted in Democrats picking people who were for hard currency for their presidential candidates even though their base nationwide was favorable to soft, or inflationary currency. When Democrats picked a New Yorker, they usually won the state. In 1868, they elected former New York Governor Horatio Seymour, and although the Republicans won the election, the Democrats won New York. In 1876, the same was true with their pick of Samuel J. Tilden. However, with the downfall of the Bourbon Democrats and the economic depression of the 1890s, New York voted for Republican William McKinley, beginning an era of Republicans being dominant in the state. These weren’t liberal guys either; at the start of the Harding Administration its senators were William Calder and James W. Wadsworth Jr., both staunchly conservative, with Wadsworth voting against the entirety of the New Deal in FDR’s first and second terms as a representative. However, the status of Republicans was starting to weaken with the gubernatorial elections of Al Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt and in 1928 even though Republicans fared quite well in that election, Hoover only won the state by two points. New York would vote for Roosevelt all four times and although it would vote for Republican Thomas Dewey in 1948, this was a plurality caused by Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party getting 8.25% of the vote. New York voted for Eisenhower twice, but I would say that its Democratic era began with the election of 1960. I say this because Republicans have only won three presidential elections since then; the 49-state landslides of Nixon in 1972 and Reagan in 1984 as well as Reagan in 1980. It is true that Republicans were still able to elect some governors and managed to hold on to one of the Senate seats for 42 years, but this was because Republicans ran candidates that were far from doctrinaire conservatives. Jacob Javits, who served from 1957 to 1981, was a textbook example of a RINO, and his successor, Al D’Amato, would probably be a bit too moderate for the modern GOP’s tastes. Perhaps Republicans have some reason for optimism in the Empire State; Trump’s performance in 2024 was the best Republicans have had since 1988.

Oregon

You might have trouble believing this, but until Michael Dukakis’ win in 1988, Oregon had voted Republican for president 81% of the time. This included the close 1960 and 1976 elections and before Wilson’s 1912 win, they had only voted Democratic in the 1868 election. The state remained fairly robust for the GOP, even when faced with FDR. Although Roosevelt won the state four times, its senators were Republican for almost the entire time. Oregon’s Charles McNary was the leader of the Senate Republicans! Oregon also had Republican governors for all but six years from 1939 to 1987. However, Oregon Republicans understood that they had to make exceptions here and there on conservatism and McNary was a very moderate conservative. The Eisenhower Administration would challenge Republican rule in Oregon based on its belief in the private sector, rather than the public sector.

In 1954, the bottom began to fall out for the state GOP, and this was due to the Eisenhower Administration’s favoring private development over public development of power. It was in that year that Republicans lost the Congressional seat based in Portland and their senator lost reelection. This would be followed by two more Congressional Republicans losing reelection in 1956. The defeated senator, Guy Cordon, stands as the last conservative to represent Oregon in the Senate. Although for 27 years Oregon had two Republican senators, neither Mark Hatfield nor Bob Packwood could be considered conservatives. Gordon Smith, who represented Oregon from 1997 to 2009, was a moderate.

Although Oregon has had a strong Democratic streak since 1988, it is also true that Al Gore won by less than half a point in 2000, and Kerry won by less than five points in 2004. However, Oregon’s Democratic politics have strengthened since then, and since 2008 the Democratic candidate has won by double digits. Oregon does not look like it will be moving to the Republican column at any time in the foreseeable future.

References

Davis, T.J. (2018, December 30). Young people are changing black politics in Delaware. Delaware Online.

Retrieved from