Many who serve in Congress don’t make it their life’s profession, but one who did was Georgia’s Carl Vinson (1883-1981). On February 14, 1914, Georgia Senator Augustus Bacon suddenly and unexpectedly died, and appointed to succeed him was Congressman Thomas W. Hardwick. Enter 30-year old Carl Vinson, a judge of the Baldwin County court who had served two terms in the Georgia House of Representatives, who was elected to succeed him on November 3, 1914. As a young representative, Vinson was a strong supporter of President Woodrow Wilson. After all, Georgia was a strongly Democratic state and indeed until 1964 its people didn’t vote for a Republican for president. Although he initially opposed the Prohibition amendment, it was popular in Georgia and he ended up voting for it. He also opposed women’s suffrage, which was the norm in Georgia politics of the time. In 1918, Vinson had a tough contest for renomination, facing the old Populist leader Thomas E. Watson, but he narrowly prevailed. This would be the last serious challenge to his reelection. Vinson’s specialty would be building up the navy, and although he focused on American presence on the seas, he was not one for international travel. He hated flying, and only once flew out of the country to visit the Panama Canal in the 1920s (Honaker). Indeed, there were a number of ways he was simply different from other people. He smoked or chewed cheap cigars and never learned to drive (Cook). Vinson also preferred simple food over fine dining. On the navy, he was of the belief that “No person representing the American people should ever place the defense of this nation below any other priority” (The New York Times). And indeed, his focus became the creation of a powerful two-ocean navy. Vinson was strongly supportive of the First New Deal but would have more difficulties in supporting the Second New Deal, which included his vote against the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. Indeed, he would butt heads with the Roosevelt Administration over the increasing power of organized labor and in 1941 he sponsored a bill to counter strikes. His role in backing the navy had increased with his ascendancy to the chairmanship of the Committee on Naval Affairs in 1931, and would play a significant role in national defense, sponsoring three key measures. These were the Vinson-Trammell Act in 1934, increasing naval construction to the limits of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, the Second Vinson Act of 1938 further increasing construction after Japan pulled out of the 1922 agreement, and his sponsorship of the Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940, which increased the size of the U.S. Navy by 70% (Hutcheson, 1541). All these measures served to create the modern U.S. Navy, and his impact on the strength of our forces in World War II was enormous. Admiral Chester E. Nimitz stated of his role, “I do not know where this country would have been after December 7, 1941, if it had not had the ships and the know-how to build more ships fast, for which one Vinson bill after another was responsible” (Cook). Known as the “swamp fox” for his supervisory role over the Pentagon from Congress, it was serious business when generals and admirals were called to testify before the House Armed Services Committee (Glass). He would serve as chairman until 1947, when the Republicans got into the majority, and in 1949 he would become chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, a post he would hold for the rest of his career with only a two year interruption when Republicans won Congress in the 1952 election. Although at one point he was supposedly being considered for Secretary of Defense by President Truman, Vinson was not interested, stating, “Shucks, I’d rather run the Pentagon from up here” (Glass).

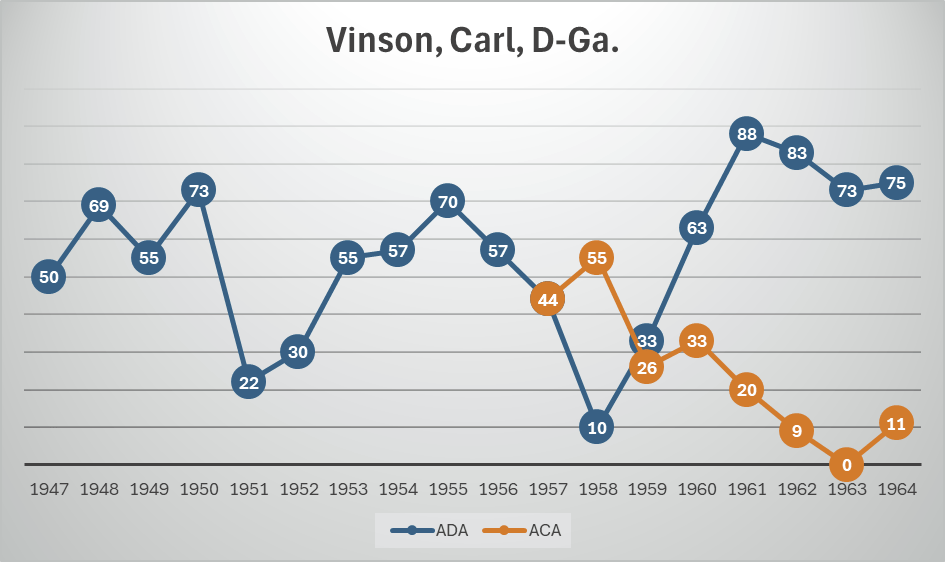

Although often considered part of the Conservative Coalition in Congress, Vinson was not nearly as conservative as you might think. He overall sided with the liberal Americans for Democratic Action 56% of the time from 1947 to 1964, and this is in part due to how he responded to the election of President Kennedy. Kennedy had his second best electoral performance in Georgia, and Vinson saw it as important to support a president who had such a mandate from the voters of his state. On January 31, 1961, he was one of only two Georgians to support enlarging the House Rules Committee, which helped key items of President Kennedy’s agenda reach the House floor, and was the only Georgian to oppose a conservative substitute to that year’s minimum wage bill. This contrasted with his support for Rep. Wingate Lucas’s (D-Tex.) conservative substitute for a minimum wage increase in 1949. Vinson also supported federal aid to education, and the Kennedy Administration’s housing bill. Indeed, he was Kennedy’s foremost champion in Georgia. Senator Sam Nunn, Vinson’s grandnephew, recounted that “One of the people he felt very close to was a young man by the name of John F. Kennedy…” (Shattuck). Vinson’s As I have covered before, the state of Georgia has On civil rights, Vinson had the politics of someone who would have been elected to Congress from the state in 1914.

The ideological Carl Vinson, the blue representing the liberal Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) agreement rates and the bottom representing the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action (ACA) agreement rates.

In 1964, Vinson announced he would not be running for reelection, stating, “My policy is to wear out, not rust out” (Glass). Indeed, there have been many stories of people who stayed in Washington far too long such as Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, James Murray of Montana, and John Sparkman of Alabama. Leaving Washington at age 81, he was the first person to have served 50 years in the House. From 1957 to 1964, Vinson had only sided with the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action 23% of the time and his DW-Nominate score was -0.212. In 1968, he was flown to Washington, D.C. for his 85th birthday and honored by President Johnson, who said of him, “Uncle Carl was my chairman, my tutor and my friend” (The New York Times).

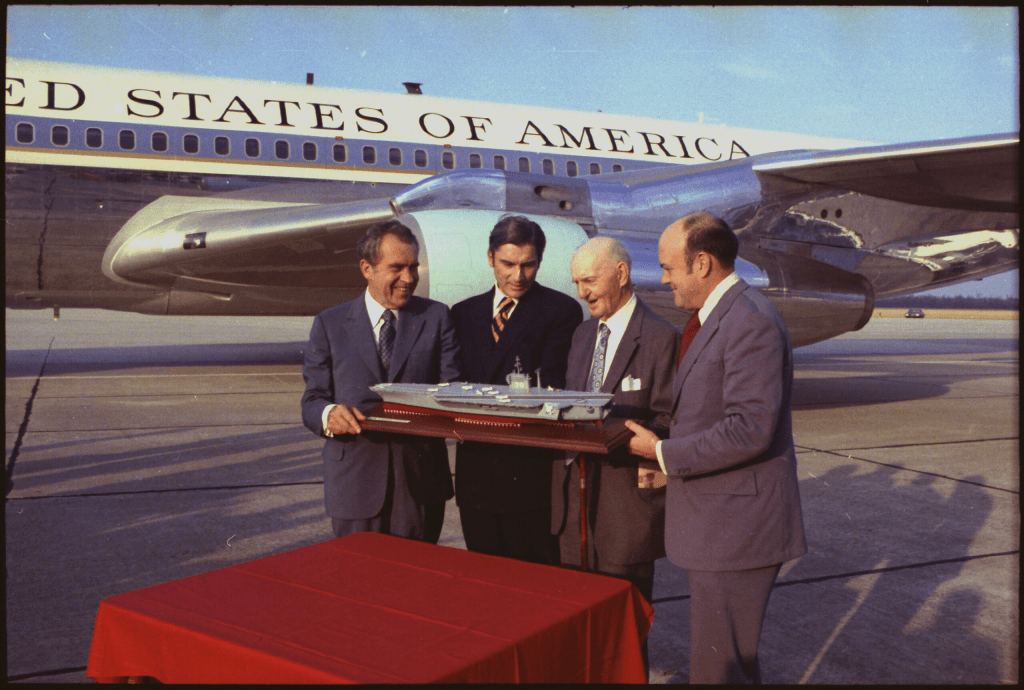

President Nixon, Secretary of the Navy John Warner, Vinson, and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird with the model of to-be-constructed USS Carl Vinson.

On March 15, 1980, Vinson, who was still alive at 96, was granted an honor that no living person had before, the launching of a navy vessel named after him. The USS Carl Vinson is a Nimitz-class supercarrier that is still in use today, and in 2011 Osama bin Laden was buried at sea from the vessel. He said on the occasion that it was “a fine way to celebrate my youthful age of 96” (The New York Times). Sadly, his wife, Mary, had not lived or thrived nearly as long, having been an invalid for years before her death in 1949. Vinson himself joined her on June 1, 1981, at 97 from congestive heart failure. In Antarctica, the Vinson Massif is named after him.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Carl Vinson, 97, Ex-Congressman Who Was With House 50 Years, Dies. The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Cook, J.F. (2002, July 11). Carl Vinson. New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Retrieved from

Glass, A. (2018, June 1). Former Rep. Carl Vinson dies at age 97, June 1, 1981. Politico.

Retrieved from

https://www.politico.com/story/2018/06/01/former-rep-carl-vinson-dies-at-age-97-june-1-1981-611008

Hutcheson, J.A. (2005). Encyclopedia of World War II: a political, social, and military history. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Shattuck, J. (2004, April 5). A Conversation with Sam Nunn. The JFK Library.

Retrieved from

Vinson, Carl. Voteview.

Retrieved from