The 1984 election was a blowout for Republicans on the presidential level but just an okay one down ticket. In the House, they gained 16 seats but in the Senate they had a net loss of two. Newt Gingrich had had some influence on President Reagan’s messaging for this election, notably his embrace of Gingrich’s proposed “opportunity society” platform. However, the 1984 election would also raise Gingrich’s profile in another way, that being the most controversial election of the year.

The “Bloody Eighth” Contest

Indiana’s 8th district, known at the time as the “Bloody Eighth”, had since its modern configuration in 1932 been a highly contested district. Up to 1985, the district had been represented by Democrats for 32 years and Republicans for 20 years. Democrat Frank McCloskey was a freshman running for reelection. He had defeated Republican H. Joel Deckard for reelection in 1982, and Republicans believed they had a good chance of retaking the district with Rick McIntyre. On election night, it appeared that they had indeed done so, with McIntyre up by only 34 votes. Indiana’s Secretary of State had given him a certificate of victory, which he presented in Washington. However, House Majority Leader Jim Wright (D-Tex.) objected to McIntyre’s seating, and the certificate had been granted on the basis of the outcome of a recount in only one of the state’s counties (Kruse). Democrats also questioned some of the election practices that occurred. For instance, there were thousands of documented cases of ballots being tossed out on technicalities, such as errors by poll workers (Kruse). Congress initiated an investigative group that had two Democrats and one Republican. The most controversial event to stem from this investigation was the casting of 94 ballots that were not notarized or witnessed from these counties, none of which should legally have been counted, yet 62 were among the count and could not be removed. 32 remained, and since the 62 were counted, the Republicans argued, the 32 should be counted as well. However, Democrat Bill Clay (D-Mo.) argued that to count the next 32 “would be to compound the problem that already exists”, but this ran counter to Democratic rhetoric of the time to count all the ballots (Kruse). The outcome of this investigation was that the committee certified McCloskey the winner by a mere four votes. Republicans regarded this as the Democrats stealing the seat and uniformly opposed McCloskey’s seating, but Democrats had a majority. Even to modern day, the surviving partisans of the event stick to their narratives on the rightness or wrongness of McCloskey’s seating. Newt Gingrich in response vowed that, “We will make it impossible for this House to function. You’ll see literal war in the House” (Kruse). There was indeed a sea change, and the language of Republicans, including ones who had been conciliatory in their language, such as Dick Cheney, changed. Cheney justified his shift, stating, “What choice does a self-respecting Republicans have…except confrontation? If you play by the rules, the Democrats change the rules so they win. There’s absolutely nothing to be gained by cooperating with the Democrats at this point” (Kruse). Republicans called for a redo of the election, but Democrats stuck by their procedure. Even Minority Leader Bob Michel (R-Ill.), golfing buddy of Speaker Tip O’Neill, said, “Things…will never be the same” (Kruse). Republicans uniformly walked out of the House in protest when McCloskey was sworn in. Now, they were far more receptive to Newt Gingrich’s bomb-thrower style. As Gingrich ally Vin Weber (R-Minn.) reflected on this, “It gave Newt credibility. Newt went from being the kind of bomb-throwing back bencher who was going to remain on the fringe of Republican politics and his ideas kept moving him steadily toward the majoritarian position in the House Republican conference. Because they saw, ‘Yeah, he’s basically right. He’s right about them. He’s right about our relationship to them. And he’s probably right about what we have to do” (Kruse). A subsequent investigation by the Evansville Courier would only further provide further fuel for the fire. Their investigation discovered that of the 32 ballots that had not been counted, 26 of the voters had managed to be contacted, and of those 20 stated that they had tried to cast their ballot for McIntyre (Kruse). Had the Democrats stuck to their rhetoric, McIntyre would have won. Republicans came to believe as Cheney did that the Democrats just changed their own rules when it suited them to win.

The Rest of Reagan’s Term

Gingrich, now having the backing of many more of his Republican colleagues, continued his partisan activity. He was unwavering in his support for the Strategic Defense Initiative (“Star Wars”) and backed nearly all of Reagan’s vetoes (South Africa sanctions was an exception). Although Republicans didn’t like Tip O’Neill for his liberalism, they would like his successor, Wright, even less.

Gingrich vs. Speaker Wright

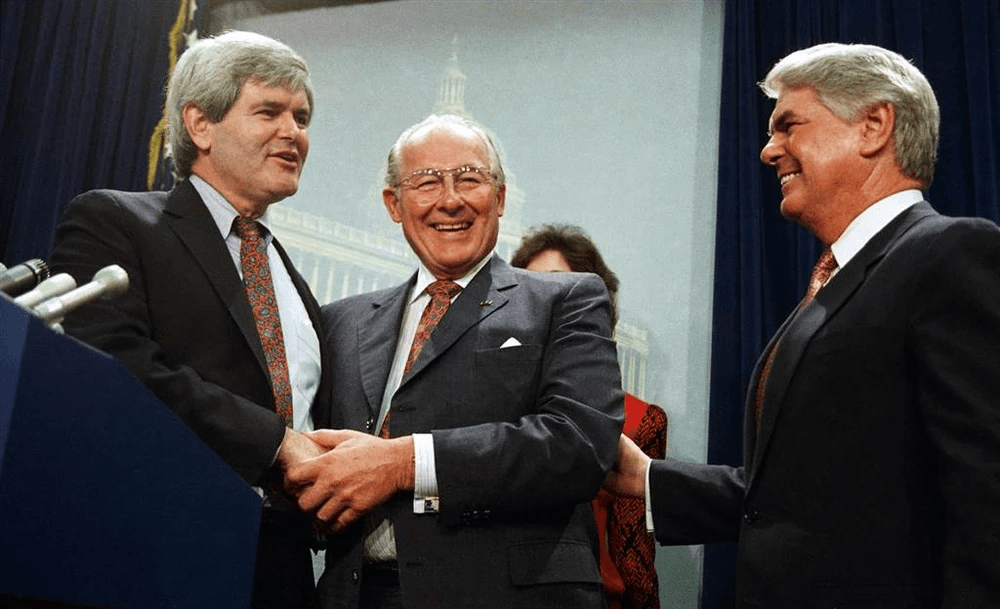

Gingrich shaking hands with Minority Leader Robert Michel (R-Ill.) after winning the post of minority whip.

With the retirement of Tip O’Neill at the end of the 99th Congress, Wright was the new speaker. Speaker Wright took a stronger partisan tone at least in part because he, like many other Democrats, were concerned about Newt Gingrich and his contingent of younger conservatives. His rule of the House was more imperious than past speakers. For example, Wright decided to completely leave out minority Republicans from decision-making and curbing staff positions for them. Rep. Vin Weber (R-Minn.) expressed the Republican discontent over Wright, “The dislike of Speaker O’Neill was ideological…he was really the symbol of northeastern liberalism. The dislike of Speaker Wright is different. Republicans think he is basically and fundamentally unfair; that he does not have the respect for the institution like Tip; that deep down he is a mean-spirited person, ruthless in the truest sense of the word” (Wallach). It also should be noted about Wright that he was mentored by Lyndon B. Johnson, so playing hardball was well within his repertoire. He also angered Republicans for attempting to negotiate with the Contras and Sandinistas despite President Reagan’s refusal and that foreign policy is foremost an executive rather than a legislative function. Gingrich suspected that Wright had skeletons in his closet and had commissioned an investigation into his background. It turns out he had suspected correctly, and in May 1988 he filed an ethics complaint against him. In March 1989, as the investigation was concluding, Gingrich was narrowly party whip to replace Dick Cheney over the considerably more moderate Edward Madigan of Illinois, who had been backed by Minority Leader Robert Michel (R-Ill.).

The Troubles with Jim Wright

There were some significant issues with Wright. The first was his business connection to Fort Worth developer George Mallick. It was alleged that Wright had accepted almost $145,000 in gifts from him since 1979 (Kelley). The second was that Wright had contravened House ethics rules on limitations on speaking fees through selling his 1984 collection of speeches, titled Reflections of a Public Man, and employed Betty to circumvent limitations on gifts. Third, he employed John Mack as his chief of staff. The problem with him? In 1973, Mack had, in a senseless act, smashed a woman on the head five times with a hammer, stabbed her in the shoulder and chest, slit her throat, and then dumped her in her car, leaving her for dead while he went to see a movie (Time Magazine). The woman survived and he had been sentenced to 15 years imprisonment for malicious wounding with intent to kill but only served 27 months in county jail. Why only 27 months? Mack had the good fortune to be the brother of Wright’s son-in-law (Time Magazine). What’s more, he was the executive director of the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee. That Mack had had this felonious episode in his past was known among Washington insiders, but for the public to hear it was shocking to them and this exposure forced Mack to resign on May 11, 1989. This wasn’t all for Wright; on April 17, 1989, he was charged with violating 69 House ethics rules. Furthermore, this was around the time of the Savings & Loan scandal, and Wright’s rise was alleged to have been assisted by S&L fraudsters including the infamous Charles Keating. The deputy head of the Federal Savings and Loan Corporation, William K. Black, alleged that Wright had intervened in favor of S& L executives. However, these allegations were not among them. Things were only going to get worse for Wright, thus he resigned on June 6, 1989, the first speaker ever to do so. Interestingly, Rep. Bill Alexander (D-Ark.) filed an ethics complaint against Gingrich in April 1989, accusing him of violating House rules with a book promotion deal in 1984, and publicly stated, “Mr. Gingrich is a congressional Jimmy Swaggart, who condemns sin while committing hypocrisy” (Los Angeles Times). He would file a second one against him as well, but on March 7, 1990, both complaints were dismissed by the House Ethics Committee as they concluded that Gingrich’s book promotion had not violated House rules or the law. After the ruling, he dismissed the charges as a “political smear…I am glad the committee was thorough, and I am happy the charges have been exposed as politically inspired nonsense” (CQ Almanac, 1990). The committee’s ruling probably saved Gingrich’s reelection, as in 1990 he had a close call for reelection, winning by only 974 votes against Democrat David Worley. However, Gingrich’s focus on ethics for Wright would come back to haunt him later, but that’s going to be in the next Gingrich post. Wright’s successor was Tom Foley (D-Wash.).

Gingrich and the “Gang of Seven”

The 1990 midterms were known as the “election about nothing” and was pretty sedate given that Democrats only gained eight seats in the House and one in the Senate. However, it did send seven new Republicans to Congress who sought to shake things up. This group, which included future Speaker of the House John Boehner of Ohio, was known as the “Gang of Seven”.

In 1992, Gingrich decided to give his tacit blessing to them in their exposure of the mismanagement of the House Bank, as he figured this scandal would do more damage to Democrats than Republicans. The House Banking scandal resulted in the convictions of four former representatives, a former delegate, and the House Sergeant at Arms. The House Ethics Committee singled out 22 representatives for leaving checking accounts overdrawn for at least eight months, and 18 were Democrats. These representatives had between 89 and 996 checks overdrawn. One of the 22, incidentally, was Gingrich antagonist Bill Alexander, who would not run for reelection in 1992. Gingrich himself had 22 overdrawn checks, but his paled in comparison to the number and length of time of the 22 representatives. This was a risky exposure for him, and he faced a significant primary challenger. That year, state legislator Herman Clark challenged Gingrich for renomination, criticizing his overdrawn checks and his use of a chauffeured limousine (The Christian Science Monitor). However, Gingrich narrowly pulled off a victory, winning by 980 votes. There would be yet another scandal with the exposure endorsed by Gingrich by the “Gang of Seven”, and this was the Congressional Post Office scandal, which resulted in Congressional Postmaster Robert Rota pleading guilty to three criminal charges in 1993 and implicating House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dan Rostenkowski (D-Ill.) and former Representative Joe Kolter (D-Penn.), who were convicted on corruption charges.

The 1994 Election – Contract with America

The 1994 midterms weighed rather heavily on the Clinton Administration for several reasons. There was a backlash against the proposed “Hillarycare”, the Brady Bill was unpopular in a number of rural areas with Democratic incumbents, and Republicans were far more energized to turn out than Democrats. Heavily inspired by President Reagan’s 1985 State of the Union Address, written by Gingrich and Dick Armey (R-Tex.), and with input from the Heritage Foundation, came the Contract with America. This document was a pledge to the American people that if Republicans got a majority they would enact eight institutional reforms as well as bring ten key bills to the floor of Congress for a vote within the first 100 days of Congress. This provided a clear message and platform for the Republicans and although the degree of this document’s impact on the election is certainly debatable, it gave Republicans a solid platform to run on and made the midterm national. Republicans won nearly 9 million more votes than they ever won in midterm elections, while the Democratic vote had shrunk by 1 million from the 1990 midterms (CQ Almanac, 1994). Republicans gained 54 House seats, getting them a 230-204 majority, while they gained 8 seats in the Senate, resulting in 52-48 majority. This was the first time in 40 years that Republicans had held a majority in the House, and they had only held the Senate for 6 of the last 40 years.

Some of the biggest defeats of the 1994 midterms were that of Speaker Tom Foley of Washington, the beleaguered Rostenkowski, and Judiciary Committee chairman Jack Brooks of Texas. As far as Gingrich and the Republicans were concerned, 1994 had granted them a mandate, so how would Gingrich and this “Contract with America” do? That is for the next Gingrich post.

References

Capitol Offense. (1989, May 15). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6702510/capitol-offense/

Formal Ethics Complaint Filed Against Gingrich by Democrat. (1989, April 12). Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-04-12-mn-1694-story.html

Gingrich Case Dismissed. CQ Almanac 1990.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal90-1112264#_

Gingrich Wins Close Race In Congressional Primary. (1992, July 23). The Christian Science Monitor.

Retrieved from

https://www.csmonitor.com/layout/set/amphtml/1992/0723/23033.html

Kelley, E. (1989, April 18). 69 Ethics Violations Cited Against Wright. The Oklahoman.

Retrieved from

Kruse, M. (2023, January 6). The ‘Stolen’ Election That Poisoned American Politics. It Happened in 1984. Politico.

Retrieved from

https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/01/06/indiana-8th-1984-election-recount-00073924

Rare Combination of Forces Makes ’94 Vote Historic. CQ Almanac 1994.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal94-1102765#_

Wallach, P.A. (2019, January 3). The Fall of Jim Wright – and the House of Representatives. The American Interest.

Retrieved from