Among the New England states, New Hampshire long had a reputation as its most conservative, and there were numerous political figures who gave it this reputation. One of the earlier ones was Jacob Harold Gallinger (1837-1918). Although praised in his life by his supporters as fundamentally American in his values, Gallinger’s life didn’t begin in America, rather he was born in Cornwall, Ontario, British Canada, but he moved with his family to the US at a young age. In May 1858, he graduated Cincinnati Eclectic Medical Institute at the head of his class and three years later he started practicing as a homeopathic doctor and surgeon in Keene, New Hampshire, moving to Concord the next year. He was an active practitioner until 1885, and sincerely believed that homeopathy was the future.

While practicing, he began a political career in New Hampshire, being elected to the state’s House of Representatives in 1872, being reelected until his election to the state’s Senate, serving from 1878 to 1880, during which he was elected Senate President. During this time, Gallinger gained a reputation as a Stalwart, or an opponent of civil service reform, which for many years would put him in direct conflict with Half-Breed William E. Chandler. He derided proponents of civil service reform as “worshipers of Grover Cleveland” (Madura). In 1884, he was elected to the House, representing New Hampshire’s 2nd district. By 1888, Gallinger was prominent enough in the GOP to second the nomination of Benjamin Harrison at the Republican National Convention. In 1888, he was elected to the State Senate, and then to the State House in 1890, but didn’t remain as he was elected to the Senate by defeating incumbent Henry W. Blair in the primary.

As a senator, Gallinger was a faithful representative of the conservative wing of the Republican Party. According to his colleague, Democrat Henry Hollis, “He believed that any man of average intelligence could get on in the world if he would be sober, industrious, and thrifty. He did not believe that the country or the Government owed any man more than this opportunity” (Congressional Record, 10). Indeed, he had risen up from humble circumstances. Gallinger’s New York Times obituary (1918) described him as “…a conservative in most of his notions, narrow in some. He was an ancient enemy of civil service reform. He didn’t believe that railroads were an abomination and a curse. He held to the old Republican gospel of ship subsidies. Firm was his faith in a protective tariff, heaven-sent, heaven-high.” He naturally did not get on with populist or progressive causes of his day, and his conflict continued with Chandler, who was now his Senate colleague. In 1899, Chandler accused him of illegally soliciting money from federal officeholders (The New York Times, 1899). However, Gallinger wouldn’t have to worry about him for long, as Chandler had increasingly been voting independently and in 1901, he was denied renomination. Gallinger now was indisputably the most powerful figure in the politics of the Granite State. He served as a leading conservative figure in the Senate, although one who could now and again exercise independence during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt.

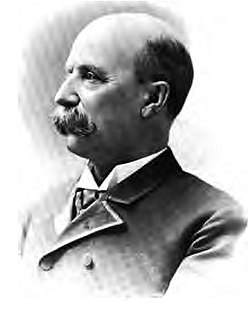

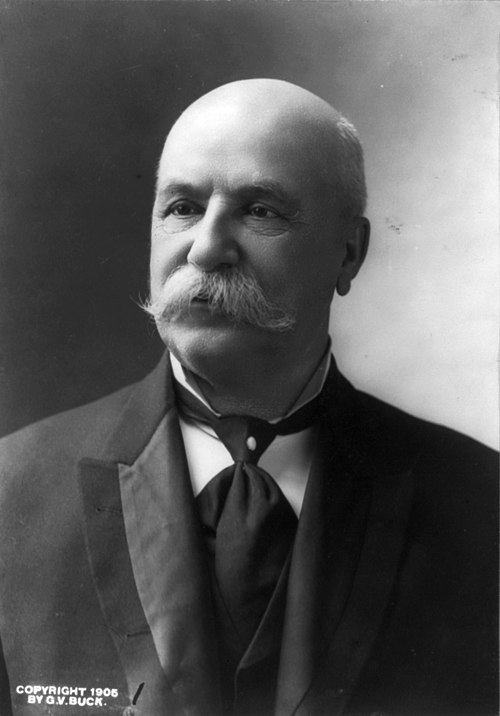

In 1911, Maine’s William Frye, a known conservative, stepped down from the Senate Pro Tem position as his health was deteriorating. Although the Senate Republican caucus supported Gallinger, eight progressive Republicans were against him, preferring Minnesota’s Moses Clapp. The Democrats wanted Georgia’s Augustus Bacon in this position, and no majority could be achieved. A strange deal was concocted in which Gallinger and Bacon would rotate in the Senate Pro Tem position on alternate days. Also serving as Pro Tem during this session were Senators Frank Brandegee (R-Conn.), Charles Curtis (R-Kan.), and Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Mass.). By the way, Gallinger and Bacon bore an amusing resemblance to each other:

Senator Gallinger

Senator Bacon

Behold! The Senate’s twin walruses!

As part of Gallinger’s deep-seated conservatism, he opposed constitutional amendments for the substitution of the electoral college with the popular vote for electing presidents and the direct election of senators. In 1912, he sided with Taft in the battle between him and Roosevelt for the Republican nomination. The following year, Gallinger was chosen by the Republicans to head the Senate Republican Conference. Before the positions of majority and minority leader existed, being the chairman of this conference translated to party leader. Thus, Gallinger led the Senate opposition to President Wilson’s New Freedom agenda. He voted against the Revenue Act of 1913 lowering tariffs and instituting an income tax, the Federal Reserve, and the Clayton Anti-Trust Act. On matters of national defense, he was a strong proponent of the growth of the US Navy, opposing efforts to cut battleship construction. In 1914, Gallinger faced his first popular election, but contrary to the hopes of the political left that popular elections would turn him out of office, he won reelection by 7 points.

His conservatism persisted after his reelection, and in 1915, the Montana Progressive characterized Gallinger as “about the most reactionary of republican senators” (1). Although most of the time he was resistant to change from what was when he came into politics, he didn’t oppose all change. For instance, Gallinger voted for women’s suffrage in 1914 and paired for the 18th Amendment (Prohibition) in 1918. As an influential senator, he was also able to wield power beyond his party numbers on occasion. For instance, in 1915, Gallinger opposed the nomination of progressive New Hampshire Republican George Rublee to the Federal Trade Commission and invoked Senatorial courtesy. Wilson was able to get him in as a recess appointment, but in 1916 his continuation had to come to a vote. Rublee had been a key figure in the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission in 1914 and had opposed Gallinger’s reelection. Under Senatorial courtesy, it is a custom of the Senate to reject nominees from a senator’s state if the senator announces that he finds the nomination is “personally offensive”. The Senate upheld the tradition of Senatorial courtesy by rejecting Rublee’s nomination 36-42. The rejection of Rublee was one of the factors that resulted in the FTC being considered ineffective in its early years by progressives. Indeed, Gallinger had been one of five senators to vote against the FTC’s establishment in 1914 (although there were numerous abstentions). In 1918, Gallinger voted for the France Amendment to protect speaking the truth under the Sedition Act and after its rejection he voted against the act itself. By this time, he was 81 years old and the oldest senator. Although Gallinger hoped and believed that he would live long enough to have a few years of retirement, that year his health was deteriorating from arteriosclerosis, and he died on August 17th. His DW-Nominate score was a 0.553, placing him solidly on the conservative wing of the GOP. He would be succeeded by the also staunchly conservative Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts. Gallinger’s Democratic colleague from his state, Henry Hollis, praised him as being of “an optimistic temperament, wholesome, sane, uniformly cheerful and courteous” while noting another’s observation of his conservative nature, “He was sure not to be “the first by whom the new is tried,” and he was always among “the last to lay the old aside”” (Congressional Record, 9).

Gallinger, I must note, is yet another case of a Republican who got his start in politics in a time in which Reconstruction was occurring who nonetheless gets characterized as a conservative by the 20th century, and yes, including in ways we would recognize today. Perhaps…the history of politics isn’t quite how the MSM has you understand it?

References

Chandler vs. Gallinger; One New Hampshire Senator’s Charges Against the Other. (1899, July 12). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Gallinger, Jacob Harold. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/3439/jacob-harold-gallinger

Jacob Harold Gallinger Memorial Addresses. (1919, January 19). Congressional Record.

Retrieved from

Madura, J. (2025, April 21). Beyond Party Lines: How One 19th Century Leader Chose Ideals Over Loyalty. Foundation for Economic Education.

Retrieved from

https://fee.org/articles/beyond-party-lines-how-one-19th-century-leader-chose-ideals-over-loyalty/

Senator Gallinger. (1918, August 18). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Senatorial “Courtesy”. Carbon County Journal, 4.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/958945960/

The “Get-Together Committee” Organized. (1915, March 18). The Montana Progressive, 1.

Retrieved from