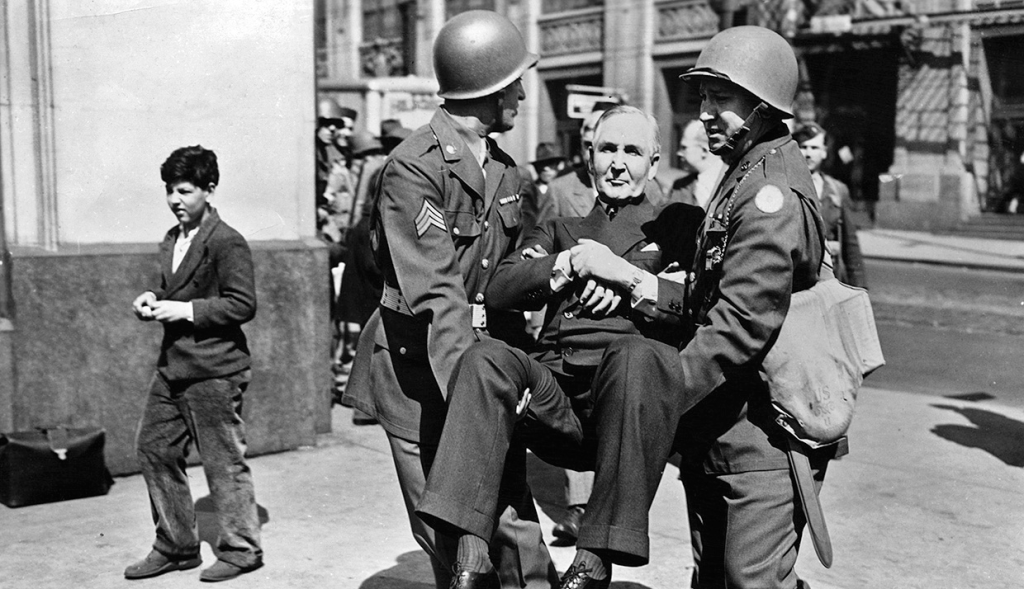

Montgomery Ward Co. CEO Sewell Avery being carried out of his headquarters as the company was being seized by the Roosevelt Administration.

World War II had a way of uniting the nation against the common enemy of the Axis powers and the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations as well as United Mine Workers among other unions agreed to a “no strike pledge” for the duration of the war in December 1941 as President Roosevelt wanted. Despite this national unity, there were still political battles at home and with wartime inflation as well as a holding down of wages given FDR’s wage freeze in the Stabilization Act of 1942, the purchasing power of the public decreased and this substantially impacted union laborers. There would be strikes during World War II despite the pledge, and the largest ones were initiated by one of America’s foremost unionists: John L. Lewis. Lewis had been a founder of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and during World War II he was the head of the United Mine Workers. In April 1943, he initiated a strike of 500,000 workers to demand better pay, compensation for travel to and from work, and safer working conditions. Walkouts occurred in April and May, disrupting coal production. For many in Washington this act was an outrage and a threat to the war effort. President Roosevelt ordered the mines seized and operated by government until a settlement could be reached. However, member of Congress wanted new legislation. Two politicians who took notice and opted for quick action were Senator Tom Connally (D-Tex.) and Representative Howard W. Smith (D-Va.). Although in the past Connally had been supportive of most New Deal measures, like many Southerners he had become alarmed at how much power organized labor had and had become more conservative over time. Smith was more hostile to the New Deal and was an arch-foe of left-wing radicalism, his dissent with Roosevelt starting considerably earlier than Connally’s. The Smith-Connally Act outlined conditions in which the president could seize and operate industries crucial to the war effort under the threat of striking and prohibited unions from making campaign contributions. President Roosevelt thought the measure too harsh on labor as did organized labor’s advocates in Congress. However, popular opinion was strongly against strikes during wartime as everyone had to make sacrifices this was the mood in Congress too. On May 5, 1943, the Senate passed its version 63-16 (D 33-11; R 30-4; P 0-1). June 4th, the House passed its version 233-141 (D 100-89; R 133-48; P 0-2; AL 0-1; FL 0-1). President Roosevelt vetoed the conference report, and the House overrode it 244-108 (D 114-67; R 130-37; P 0-2; AL 0-1; FL 0-1) on June 25th and the Senate did so on the same day 56-25 (D 29-19; R 27-5; P 0-1). There were even a few politicians of liberal reputations who voted for this measure such as Florida’s Senator Claude Pepper, who normally opposed legislation curbing organized labor’s power. Indeed, Southern support for this measure was extremely strong; among the representatives of the former Confederate states, only six voted or paired against passage and five voted or paired against overriding President Roosevelt’s veto, and no senators from these states opposed. Interestingly, Senator Harry S. Truman of Missouri voted for the Senate’s original version of the Smith-Connally Act only to vote against overriding President Roosevelt’s veto. For the most part, Truman would be a big backer of organized labor during his presidency.

This would be the first and only time a bill that was strongly opposed by organized labor would be passed over President Roosevelt’s veto. He nonetheless invoked this law multiple times to crack down on strikes. On August 1, 1944, numerous white workers went on a “sick out” for six days over the promotion of black workers to motormen and conductors required by the Fair Employment Practices Committee (these positions had been de facto “whites only”), and Roosevelt broke the strike by sending 8,000 troops to operate the transit system and threatened workers with being drafted if they did not return within 48 hours. This was certainly an ironic consequence of a law sponsored by segregationists. Roosevelt also applied this law to management when on April 25, 1944, and again on December 27th, he had Secretary of War Henry Stimson seize Montgomery Ward Co. after the company refused to abide by a labor agreement that the War Labor Board had hammered out and soldiers physically escorted the defiant 70-year-old CEO Sewell Avery, a staunch conservative, off the premises on April 27th after he refused to leave.

The Smith-Connally Act was an answer to a wartime situation and once the war was over, the law was no longer appropriate. Congressional conservatives sought to enact a peacetime substitute in a bill sponsored by Francis Case (R-S.D.) in 1946, but President Truman considered the measure too harsh and vetoed it. Congress would be even more conservative after the next election and pass the similar Taft-Hartley Act in 1947, this time over President Truman’s veto, which repealed the Smith-Connally Act and established among other things that states could decide whether to be “right to work” or not, a controversial provision that remains law. Although derided as a “slave labor law” at the time by its opponents and thought to be an effort to destroy unions, this did not prove the case. Indeed, union membership increased by three million in the ten years that followed, thus if destroying unions had been the intent of the crafters of Taft-Hartley, the law was a miserable failure.

References

Glass, A. (2016, December 26). FDR seizes control of Montgomery Ward, Dec. 27, 1944. Politico.

Retrieved from

https://www.politico.com/story/2016/12/this-day-in-politics-dec-27-1944-232931

Hunt, K. (2024, August 1). In Philly 80 years ago, a racist subway strike paralyzed the city in the middle of World War II. Philly Voice.

Retrieved from

https://www.phillyvoice.com/philadelphia-subway-transit-strike-1944-wwii-national-guard/

The Smith-Connally Act and Labor Battles on the Home Front. (2023, June 22). National World War II Museum.

Retrieved from

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/smith-connally-act-and-labor-battles-home-front

To Override Veto of S. 796, a Bill Concerning the Use and Operation of War Plants for the Prosecution of the War. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/rollcall/RH0780062

To Override Veto on S. 796, Prevention of Strikes in Defense Industries. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/rollcall/RS0780061

To Pass S. 796… Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/rollcall/RH0780047

To Pass S. 796, a Bill Relating to the Use and Operation by the U.S. of Certain Plants in the Interest of the National Defense. Voteview.

Retrieved from