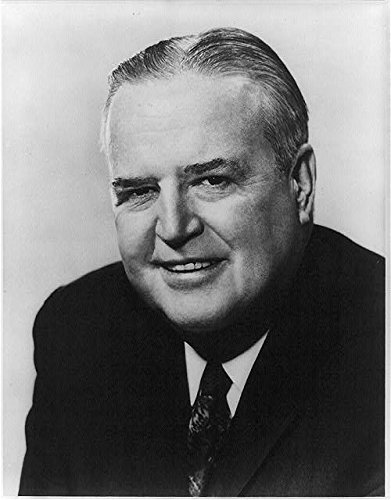

Louisiana’s politics, like the South’s generally, had a considerable shift in the 20th century. One of the figures who proved among the more resistant to the state’s increasing shift to the right was James Hobson Morrison (1908-2000).

Morrison was an attorney by profession who frequently supported organized labor, including creating a union for strawberry pickers. As a young man, he made a critical connection with Huey Long, but Long was assassinated before he could win a major office. Morrison was highly ambitious, unsuccessfully running in the Democratic primary for governor in 1939 and 1944. However, it would be between these runs in which he would have his major successful race.

In 1942, Morrison defeated anti-Long incumbent Jared Y. Sanders, Jr., for renomination. This would be the start of a long career for him, and although he had a reputation over his career as a progressive populist, in truth his earlier record was a bit more mixed. His first Congress was the 78th, in which although Democrats maintained their majority, it acted much like a Republican Congress and Morrison sometimes voted with the Conservative Coalition, including some tax votes and in voting for the Smith-Connally Act to resolve labor disputes over President Roosevelt’s veto. This early vote on labor demonstrated he could be independent from his union background, much like his vote for the Hobbs Act in 1945. However, Morrison was at heart a union man and in 1946 he voted against the proposed Case bill as too harsh on labor. Morrison’s record on price control was mixed, supporting some limitations but supporting the general concept. Morrison also championed highway projects in his Baton Rouge-based district.

At the end of World War II, Morrison controversially sponsored a bill that provided for the relief of Sylvestro “Silver Dollar Sam” Carolla from deportation by making him a naturalized citizen. Carolla was the boss of the New Orleans crime family. This bill did not pass, and he was deported in 1947.

Morrison had a mixed record during the Republican 80th Congress. He voted for several Republican-pushed measures such as tax reduction legislation and the Reed-Bulwinkle Act during the 80th Congress but was also one of the few Southerners to vote against the Taft-Hartley Act. Morrison proved one of the more favorable Southerners to President Truman’s Fair Deal, but it would not be until the Eisenhower Administration in which he was firmly identified with the liberal wing of the Democratic Party.

Morrison proved second only to New Orleans’ Hale Boggs among Louisiana supporters of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, supporting most New Frontier and Great Society measures. He voted for accelerated public works, minimum wage legislation, public housing, anti-poverty legislation, federal aid to education, and Medicare. He even bent on an area in which tough to do for his region: civil rights.

Morrison had signed the Southern Manifesto and had not supported a single civil rights measure until his vote for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, being one of two Louisianans to vote for it. His vote for this plus his strong support of the Great Society made him a target for defeat for renomination as LBJ was not popular in his district, which had voted for Barry Goldwater in 1964 (Western Washington University). This opened him up to a primary challenge from segregationist Judge John Rarick. Rarick was a staunchly conservative figure who had a history of racism, once telling a black lawyer who entered his courtroom, “I didn’t know they let you coons practice law” (Time Magazine). Morrison campaigned against Rarick by publicizing his ties with the KKK. Rarick denounced him as a candidate of the “black power voting bloc” (Webb). Morrison had an uphill battle as a strong LBJ supporter as much of his previous support was bleeding away. Rarick had also campaigned against Morrison as a “handmaiden to LBJ” (The Town Talk). The Democratic primary’s first vote resulted in a runoff, which Rarick won. Morrison never ran for public office again, resuming his legal career and raising money for Southeastern Louisiana University. He had agreed with the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action 12% of the time from 1957 to 1966, the liberal Americans for Democratic Action 64% of the time from 1947 to 1966, and his DW-Nominate score was a -0.28.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

1964 United States Presidential Election, Results by Congressional District. Western Washington University.

Retrieved from

Lawyers: Harassment in the South. (1968, August 16). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,838559,00.html

Mearns, G. (1966, September 26). Rarick Beats Morrison In House Race. The Town Talk, 21.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/215830230/

Morrison Defeated in 6th District. (1966, September 25). The Shreveport Times, 1.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/213448882/

Morrison, James Hobson. Voteview.

Retrieved from