The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is aiming to find waste, inefficiency, and areas to cut government spending. One subject that they have touched on is veterans benefits as has prospective Trump nominee to the post of Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth. On that one from a historical perspective, they are in for one hell of a fight! Veterans’ benefits have a long history of being politically difficult to resist. In 1949, for instance, the House by only one vote rejected Veterans Affairs Committee chairman John Rankin’s (D-Miss.) measure that would have provided for a massive pension program for World War I and World War II veterans at $90 a month (or $1,193.69 in October 2024 dollars) starting at age 65 that at the same time would have served to fiscally prevent President Truman from expanding Social Security as he planned (Time Magazine). The measure’s defeat was in no small part due to the vocal opposition of certain World War II veterans in Congress, most notably Olin “Tiger” Teague of Texas, the second-highest decorated soldier of the war. Even President Roosevelt at the height of his power struggled with the issue.

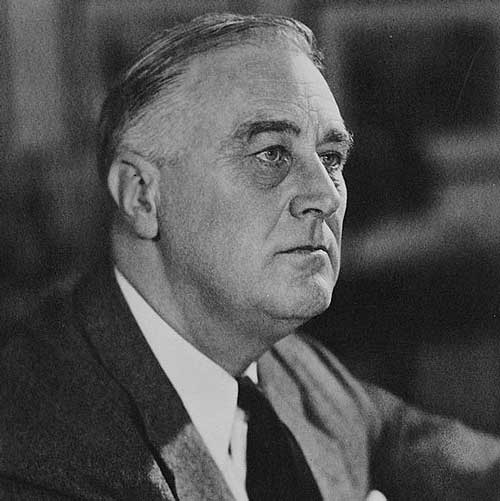

Speaker Henry Rainey (D-Ill.) was perfectly willing to let the executive branch write laws and have the House rubber stamp them, but there was a fight in the early New Deal that Roosevelt lost, and not even the opposition of Speaker Rainey could overcome this, and this was on funding New Deal programs in part through cuts in veterans’ benefits.

The first New Deal law to pass, and one that actually got substantial support from conservatives, was the Economy Act, which cut spending for the purposes of making room in the budget for FDR’s New Deal programs and served to effectively repeal all laws passed after the War of the Rebellion for veterans’ pensions, granting FDR the power to restructure veterans’ benefits, and he did so by cutting benefits by over $400 million. This provoked a lot of bipartisan opposition, including from individuals thought of as progressive in this time, such as Senator Burton Wheeler (D-Mont.). On June 14, 1933, the Senate responded to FDR’s veterans’ benefits reduction with the Steiwer (R-Ore.)-Cutting (R-N.M.) amendment 51-39 (D 19-39; R 31-0; P 1-0) to the Independent Offices Appropriations bill, which if enacted into law would have only permitted Roosevelt to cut up to 25% of an individual veteran’s benefits, amounting to a maximum overall reduction between $100-160 million. Interestingly, this vote presaged further opposition to Roosevelt’s agenda in the future, most notably on foreign policy, from certain senators who were at least nominally for the New Deal at this point, including Wheeler, Pat McCarran of Nevada, and Robert R. Reynolds of North Carolina. This was also a point of contention between the flamboyant Huey Long of Louisiana and the president. Roosevelt was prepared to veto the bill if the amendment remained, but the House came to his rescue and refused to adopt Steiwer-Cutting 177-209 (D 79-201; R 93-8; FL 1-0) the following day. However, the battle was far from over on veterans’ benefits, the most hotly contested part of the Economy Act, and the House voted to increase veterans benefits to largely offset Roosevelt’s cuts. Although President Roosevelt vetoed the bill, the House overrode his veto of the bill 310 to 72 (D 209-70; R 97-2; FL 4-0) on March 27, 1934. Among Republicans, only Robert Luce and George Tinkham of Massachusetts, normally opponents of Roosevelt and the New Deal, voted against this effort. Although Majority Leader Robinson (D-Ark.) was more successful at persuading his fellow Democrats to sustain Roosevelt’s veto, his veto was overridden the following day 63-27 (D 29-27; R 33-0; FL 1-0) that same day. This would be predictive of the override of another of President Roosevelt’s vetoes, on the Patman Bonus bill. Like President Hoover before him, Roosevelt opposed the Patman Bonus bill, which permitted veterans to collect their bonuses at any time as opposed to 1945 as established by the 1924 World War Adjusted Compensation Act as a budget-busting measure. Unlike with the appropriations bill, he got some sizeable conservative Republican support for his position. Although the House overrode President Roosevelt’s veto on May 22, 1935, 322-98 (D 248-60; R 64-38; P 7-0; FL 3-0), Majority Leader Joseph Robinson (D-Ark.) was successful in getting the Senate to sustain the veto the following day 54-40 (D 41-28; R 12-12; P 1-0). However, a compromise Patman bill was pressed into 1936. This one managed to pass over President Roosevelt’s veto, with members of Congress feeling more pressure as the next election approached. The House voted to do so on January 24th 326-61 (D 249-32; R 67-29; P 7-0; FL 3-0) and the Senate voted to do so 76-19 (D 57-12; 17-7; P 1-0; FL 1-0) three days later. Although veterans’ organizations advised veterans to wait until 1945 to collect, many chose to do so right away. This measure would essentially serve as a stimulus for veterans. Roosevelt would later do quite well for veterans in his signing of the GI Bill in 1944.

References

Ortiz, S.R. (2009). Beyond the Bonus March and GI Bill: How Veteran Politics Shaped the New Deal Era. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Retrieved from

Senate Votes 51 to 39; Adopts New Increases for Veterans Despite Leaders’ Pleas. (1933, June 15). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/1933/06/15/archives/senate-votes-51-to-39-adopts-new-increases-for-veterans-despite.html

The Congress: Rankin’s Revenge. (1949, February 28). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6602178/the-congress-rankins-revenge/

To Amend H.R. 5389, by Amending Sec 20, Authorizing President to Establish Review Boards Dealing with Veterans Pensions. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/73-1/s97

To Concur in an Amendment to H.R. 5389. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/73-1/h61

To Override the President’s Veto of H.R. 3896. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/74-1/s69

To Override the Veto of H.R. 9870. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/74-2/s138

To Pass H.R. 3896, the Objections of the President of the United States Notwithstanding. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

To Pass H. 9870 Over the Objections of the President of the United States. Govtrack.

Retrieved from