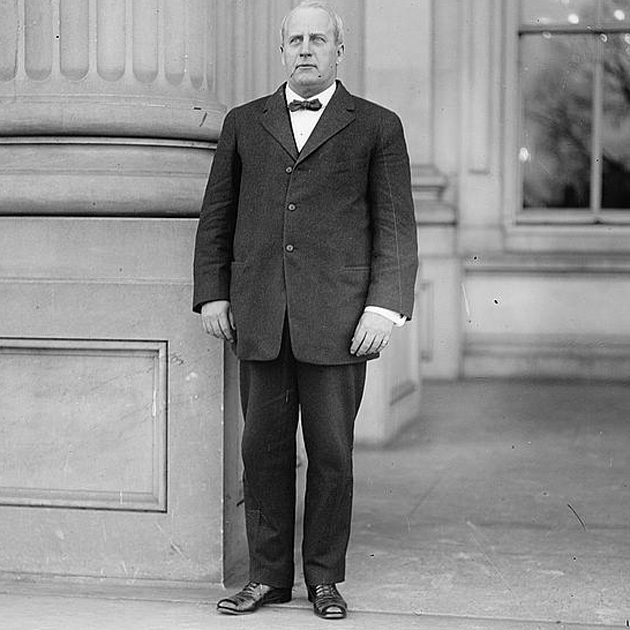

John A. Sterling (R-Ill.), Republican advocate of worker’s compensation.

Although worker’s compensation is often considered a progressive advancement as it is a benefit to workers, the debate surrounding a worker’s compensation measure in 1913 as well as the debate surrounding it paint a different picture. The bill in question, S. 5382, if enacted would grant an exclusive remedy and compensation for accidental injuries resulting in disability or death to employees of railroad companies engaged in interstate or foreign commerce and for the District of Columbia. On its face, it looks like a progressive measure and that it provides evidence for Republicans being the progressive party of the time. The House vote was 218-81, with 100 Democrats, 116 Republicans, 1 Progressive Republican, and 1 Socialist voting for, while 79 Democrats and 2 Republicans voted against. However, when we look into the debate surrounding the legislation, the political contours appear different.

A champion of the legislation, John A. Sterling (R-Ill.), praised it thusly, “This bill is in harmony with the spirit of the age and enlightened civilization. It lifts the burden of industrial accidents from the shoulders of those least able to carry it and places it where it belongs. Why should the injured man or his family bear all the loss incident to accidents in the operation of these great quasi public enterprises. Railroads are operated for the benefit of society, and society should bear the burden imposed by them…Not only are the railroad men of the country demanding it but humanity requires it…It is intended to give prompt and adequate relief to the injured man in the hour of his need and to his widow and children in case of his death. It is in harmony with Christian civilization, and its adoption is imperative if our Government is to keep step with the onward march of progress. These new industrial conditions which have sprung up in the last half century have necessitated this revolution in legislation pertaining to this subject. The old laws should be abrogated, because our civilization has outgrown them. The time has come when we must strip ourselves of laws which, although good in their day, are now holly inadequate to meet the new conditions” (Congressional Record, 4481).

However, John Floyd (D-Ark.) was not having it, “The distinguished gentleman from Illinois who has just closed his remarks says that it is the most generous compensation act ever proposed in a legislative body. Yes; for the railroads, but it is the most outrageous, unjust, and damnable law that was ever brought forward in the name of virtue. It is the favorite method of those who seek to procure the enactment of bad legislation to seize upon and champion some popular idea or sentiment and then accomplish their ulterior purpose by indirection. That is what is sought by this legislation. This legislation originated with the claim agents of the great railroad systems of this country as disclosed in the hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary of the House” (Congressional Record, 4481).

Robert Henry (D-Tex.) also opposed this bill as limiting worker’s rights, “For 10 years we endeavored to pass the employers’ liability bill, abolishing the barbaric doctrine of assumed risk, contributory negligence, and the doctrine of fellow servant. And no sooner had we abolished them and established that law than the railroads began the crusade to repeal it; and to-night they come into this Congress, in the closing hours, and endeavor to repeal that act and shut the courthouse doors of every State in this Union against these litigants. If you give the litigant the right to elect his remedy and go into court and assert his remedy, if he sees proper, I will vote for the bill. Let the courthouse doors be open so that the litigant may assert his right in the courts” (Congressional Record, 4502).

There were those, however, who thought this was a step in the right direction despite its accused benefits to railroads and limitation to possible remedies. Rep. David J. Lewis (D-Md.), a former member of the Socialist Party who would later in life be a staunch New Dealer and prime crafter of the Social Security Act, embraced the bill, stating, “Mr. Speaker, in the coming year 90,000 men are to be injured on our railroads and 10,000 killed. That is as much to be expected as the orderly operation of the planets themselves. Under existing law less than one-third of these victims will receive some $15,000,000, certainly not more than $20,000,000 with their lawyers to pay. Under the bill that is presented to the House to-night all the victims will be compensated and that sum will be lifted to from $48,000,000 to $60,000,000 as compensation to the victims of industry” (Congressional Record, 4502).

However, Adolph J. Sabath (D-Ill.), who would serve as a staunch liberal until his death in 1952 and would be a strong New Deal supporter, had this to say about the legislation, “Mr. Speaker, in the short space of time allotted to me all I can hurriedly say is this: I am heart and soul in favor of a workmen’s compensation bill which will provide for compensation to employees that are injured or killed; in fact, the first workmen’s compensation bill considered by this House was introduced by me during the first session of the Sixtieth Congress, nearly six years ago. Since that time I have devoted a great deal of time and have expended large sums of money in an effort to acquaint the people with the principle underlying workmen’s compensation and in endeavoring to convince them of the merits of this legislation. Therefore I regret exceedingly that after struggling for six years to secure workmen’s compensation I can not cast my vote for the bill which is now before the House, for it is a compensation bill in name only; it should rightfully be called the “Railroad relief measure.” Nearly every section is so drafted as to be in the interest of the railroads. It provides that this shall be the exclusive remedy that employees shall have and takes away from them their present statutory and common-law rights. Since the very beginning of my fight for workmen’s compensation I have contended that such legislation should not deprive the injured employees of any rights which they now enjoy, but should give them additional protection…” (Congressional Record, 4503).

For another matter of interest, let’s look at some figures who served in Congress during the Roosevelt Administration and voted on this proposal:

Carl Hayden (D-Ariz.) – Nay – New Deal supporter in the Senate.

William B. Cravens (D-Ark.) – Nay – New Deal supporter.

John A. Martin (D-Colo.) – Yea – New Deal supporter in the House.

Adolph J. Sabath (D-Ill.) – Nay

Henry Rainey (D-Ill.) – Nay – Speaker of the House who shepherded FDR’s First 100 Days legislation.

Finly Gray (D-Ind.) – Yea – Largely supportive of the New Deal.

David J. Lewis (D-Md.) – Yea

James Curley (D-Mass.) – Yea – Overall moderately liberal.

Pat Harrison (D-Miss.) – Nay – A staunch supporter of the New Deal during FDR’s first term, but in his second term he started calling for tax and budget reductions.

Hubert Stephens (D-Miss.) – Nay – Although a progressive, his reception to the New Deal was considered lukewarm and he lost renomination to the Senate in 1934.

Clement Dickinson (D-Mo.) – Nay – New Deal supporter.

George Norris (R-Neb.) – Yea – New Deal supporter, left the GOP in 1936.

Edward Pou (D-N.C.) – Nay – New Deal supporter for his last year in office.

Robert Doughton (D-N.C.) – Nay – House sponsor of Social Security, but he became considerably more right-wing in the 1940s.

William Ashbrook (D-Ohio) – Yea – Never the most liberal of Democrats, Ashbrook would turn sharply against the New Deal during FDR’s second term. He was also the father of ultra-conservative Republican Congressman John Ashbrook.

Robert Bulkley (D-Ohio) – Yea – Independent in voting, a sometimes supporter of the New Deal as a senator.

Benjamin Focht (R-Penn.) – Yea – A moderately conservative to conservative legislator who backed a few New Deal measures.

James F. Byrnes (D-S.C.) – Nay – One of the Senate’s foremost champions of the first New Deal and essentially assistant president on domestic issues during World War II. He would after his time in the Roosevelt Administration shift to the right and backed Republican candidates for president from 1952 onwards.

Kenneth McKellar (D-Tenn.) – Yea – A progressive who shifted a bit to the right during the 1940s, and although he was a consistent supporter of the Tennessee Valley Authority, he feuded with its head, David Lilienthal.

Carter Glass (D-Va.) – Paired for. – A senator by the time of the New Deal, Glass was, along with Thomas P. Gore (D-Okla.), among the most hostile of Senate Democrats to FDR’s New Deal.

Ultimately, the problems the detractors of this legislation, who were of the left in Congress at the time, involved not worker’s compensation as a concept, rather that there was an “exclusive remedy”, this being viewed as favorable to railroads. It was, but streamlining the process for workers and setting up an automatic system was seen as a benefit for them as well. This is why this measure got the support of some who would champion the New Deal later, like Lewis. While there were divisions among the left in Congress over this, there were no significant ones among the Republicans. Figures that no historian disputes were conservative were voting for this, such as former Speaker of the House Joe Cannon (R-Ill.). John A. Sterling himself scores a 0.469 by DW-Nominate.

References

Sterling, John Allen. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/8900/john-allen-sterling

To Suspend Rules and Pass S.5382… Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/62-3/h257

Workmen’s Compensation Bill. (1913, March 1). Congressional Record, 4476-4548. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Retrieved from