William Sprague IV (1830-1915) was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, as his family had established the A&W Sprague Manufacturing Co. in Cranston, Rhode Island. This business owned a Calico-printing mill in Cranston as well as five textile mills in New England (Musil). Furthermore, it produced numerous products with iron. Being a wealthy businessman proved then as it does now to be a quick path to politics, and in 1860 he was elected governor of Rhode Island at the age of 29 as a Conservative. This meant that he stood in contrast to the Republican candidate and thus he got support from a broad swath of the electorate not willing to go with Radical Republicanism. As governor, Sprague got a law passed weakening protections for escaped slaves from capture by slave catchers. However, he also was a strong unionist and assembled troops to back the effort before President Lincoln even asked (National Governors Association). Sprague also served in the War of the Rebellion as a Brigadier General and was awarded for bravery in 1862 for his conduct during the Battle of Bull Run. Although as governor, Sprague’s policies hadn’t been the friendliest towards blacks, he assembled the state’s first black regiment. His war heroism attracted the attention of Rhode Island political boss Henry B. Anthony, who with Sprague’s father-in-law Salmon P. Chase got him to run for the Senate in 1863 as a Republican.

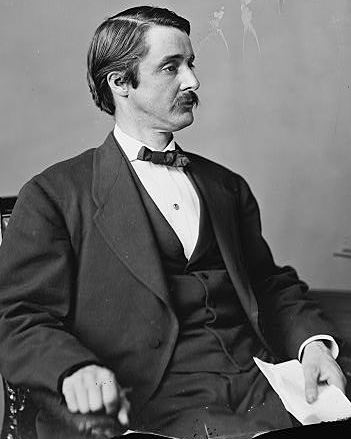

Senator Sprague

Although initially Sprague voted in line with Republicans, it didn’t take long for him to start getting into conflict with Anthony, who ran what was called the “Journal Ring”, with the prominent Providence Journal, which he owned, backing him, his candidates, and their positions. Although Sprague had staunchly supported the war effort, the Union blockade on trading cotton with the Confederacy placed a substantial burden on his business, and his plea to the federal government to allow him to trade with the Confederacy was denied. Thus, when Texas blockade-runner Henry Hoyt proposed a scheme by which he could sell supplies and arms to the Confederacy in exchange for cotton, he agreed to it (Musil). The scheme involved Confederates providing cotton in Matamoros, Mexico to a British middleman who could transport the cotton from Mexico to the United States under a British flag. However, this scheme was exposed in December 1864 after Union officials got Charles Prescott, who worked as a skipper on one of the ships, to confess the whole scheme (Musil). Sprague quickly wrote a letter denying the scheme to Major General Dix. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton covered this scandal up, but this meant that Sprague was vulnerable to blackmail. Although extremely reluctant to vote to convict President Andrew Johnson as Salmon P. Chase was pushing him to vote against, Senator Anthony, who had been crossed by Johnson in his patronage picks for Rhode Island, threatened Sprague with political oblivion if he did not do so (Warwick History, Part III).

Sprague and President Grant

William Sprague soon came into conflict with President Ulysses S. Grant, and he was often voting against what his party was standing for, resulting in Anthony firing at him with both barrels in the Providence Journal. The Journal portrayed him as an alcoholic (which he was) and a madman and condemned his stances as a Liberal Republican. His DW-Nominate score was a 0.122, on the liberal end of Republicans of the time. In 1872, Sprague backed the candidacy of Horace Greeley. By the next election in 1875, he had no chance of success against Anthony, who had picked former General Ambrose Burnside to succeed him. Sprague’s political career was over.

Personal Life

Although Sprague had been a war hero, he was a deeply flawed man. He was narcissistic, and it negatively impacted every relationship. He talked down to employees at his mills and to anyone he saw as lower than him, his First Rhode Island Regiment got so sick of him they just left, but his wife Kate Chase got the brunt of it (Sullivan). Kate Chase was attracted to him as he came off as debonair and a rogue, but the marriage was a huge mistake. His drinking worsened into alcoholism, and he would spend his great wealth primarily on himself and was stingy with his allowances to Kate and their children, to the point that purchasing necessities for the household was neglected (Sullivan). He also carried on affairs and was abusive, including one incident in which he tried to push Kate out of a window. Sprague would often communicate to his wife in writing in which it was clear that he regarded her as a burden. The alcoholism, abuse, and estrangement led to Kate having an affair of her own with prominent Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York, who in contrast to the ugly and short Sprague was tall, athletic, attractive, and seldom drank. This went on for a few years until Sprague caught them together and chased Conkling out of his home with a shotgun. Despite his alcoholism, he remarried and died one day before his 85th birthday, but faced the tragedy of having his only son take his life at 25, which Kate blamed him for (Sullivan).

References

Foster, F. S. (2015, June 8). Kate Sprague and Roscoe Conkling: Beauty and the Boss. Presidential History Blog.

Retrieved from

Henry Bowen Anthony 1815-1884 – A brilliant editor and politician. Warwick Rhode Island Digital History Project.

Retrieved from

Musil, M. (2017, December 26). Money Out of Misery. HistoryNet.

Sprague, William. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/8806/william-sprague

Sullivan, K. (2019, April 10). The narcissism of William Sprague. Warwick Beacon.

Retrieved from

https://warwickonline.com/stories/back-in-the-day-the-narcissism-of-william-sprague,141417

William Sprague. National Governors Association.

Retrieved from