Like many men of his generation, William Jennings Miller (1899-1950) was a veteran of the first World War. Unlike many men of his generation, his injuries occurred shortly after the war’s conclusion. Miller was test-flying a plane and it crashed. He suffered a broken back as well as the loss of both of his legs, and spent four years in the hospital. Despite this crushing loss, Miller proceeded with life after being released. He got married and launched a successful insurance career in Hartford, Connecticut. Miller also was active in the American Legion, becoming Connecticut’s commander in the 1930s. In this position, he simultaneously fought for generous benefits for disabled veterans while taking a fiscally conservative stance in opposing adjusted compensation certificates, and during his tenure membership reached record levels (Congressional Record, 16000). Miller’s success in insurance as well as in the American Legion put him in a good position to run for public office, and in 1938 he challenged Democrat Herman P. Kopplemann for reelection. This was a good time to run as it was the first election since 1928 that went in a Republican direction, and he was among the winners. This election started a ten-year cycle of boom and bust for the parties in Connecticut.

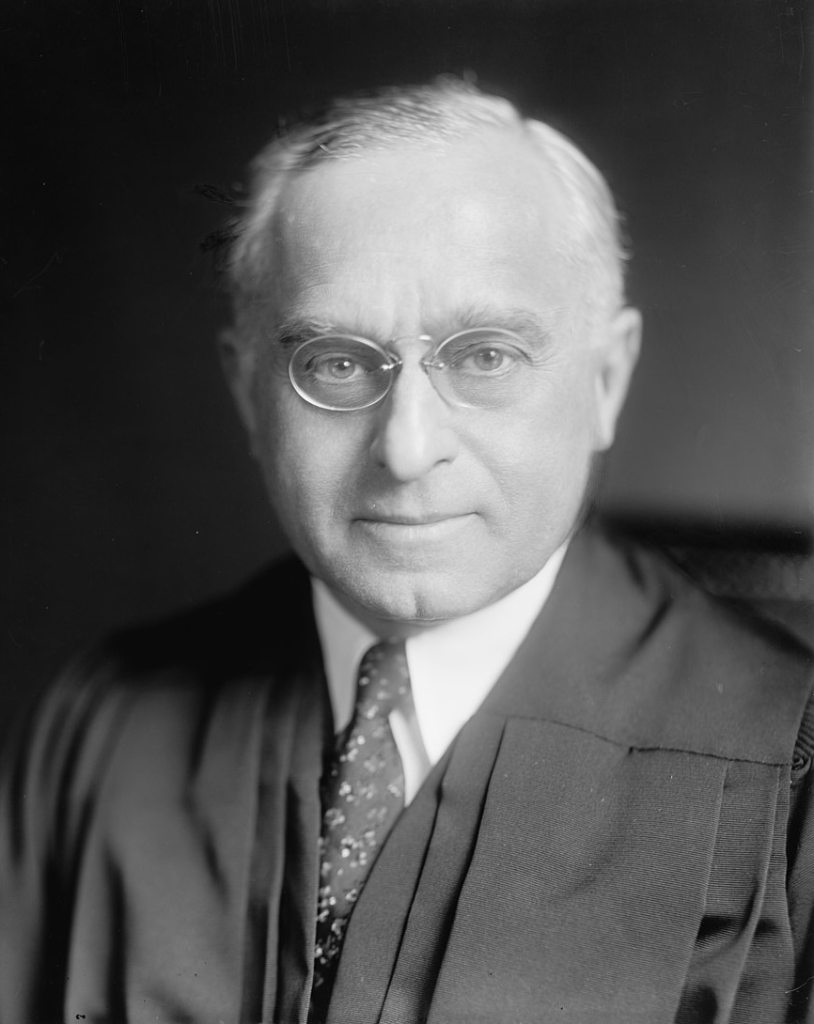

Congressman Miller

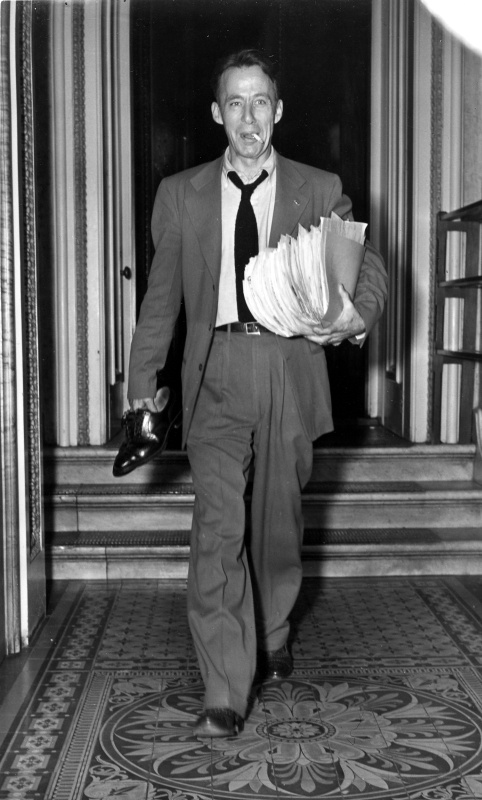

Miller was a happy warrior while in Congress, persistently cheerful despite his disability and known as “Smiling Bill”. His attendance record was solid and as an active member of the American Legion he specialized in veterans’ affairs. Miller encouraged veterans, injured and not injured alike, to not rely on the government whilst advocating for them. He proved fiscally conservative, voting against work relief appropriations in 1939. However, on social issues he proved liberal. Miller was one of less than ten Republicans to oppose the Hobbs bill in 1939 that would have provided for detention facilities for illegal immigrants. Miller also supported anti-lynching legislation, which while you might think this would be a given in Connecticut, his Republican colleague, Thomas Ball of the 2nd district, voted against. He was also opposed to the US getting involved in World War II, voting against the Neutrality Act Amendments in 1939 and against the peacetime draft in 1940. 1940 was a good year for the Democrats in Connecticut, and all House Republican incumbents lost reelection, with Kopplemann returning to office. However, in 1942, Miller ran again and defeated Kopplemann a second time.

During the 78th Congress, Miller was staunchly independent in his voting. He voted against appropriations for the Dies Committee, for income tax relief, against further funds for the National Youth Administration, and against the Smith-Connally Act. The latter provided a mechanism for stopping wartime strikes and it was enacted in 1943 over President Roosevelt’s veto. Miller further voted against multiple efforts to weaken wartime price control, voted against soldier voting bills that placed the criterion of who would get mailed a ballot with the States as opposed to the Federal government, voted to ban the poll tax in Federal elections, supported generous benefits for defense workers, supported legislation curbing subsidies, and supported freezing the Social Security tax at 1%. 1944 was, although not the blowout year for Connecticut Democrats that 1940 was, still a good year as four of six of the Republican representatives were not returned to office, with Miller again losing to Kopplemann. In 1946, however, Republicans again had a clean sweep of the Connecticut delegation, with Kopplemann losing reelection for the last time to Miller. During the Republican 80th Congress, he supported income tax reduction over President Truman’s veto, the Taft-Hartley Act over President Truman’s veto, banning the poll tax for Federal elections, the Reed-Bulwinkle bill easing anti-trust laws on railroads, budget cuts to multiple departments, and the Marshall Plan. However, he demonstrated his independence and his general aversion to anti-subversion measures in being one of only eight House Republicans to vote against the Mundt-Nixon bill for the registration of Communists with the Attorney General. Although Miller opposed cuts to aid to Europe, he nonetheless voted against aid to Greece and Turkey in 1947. I have not been able to find out the why but his voting on other foreign aid measures suggests that his rationale may have been similar to that of a small group of Democratic liberals who opposed such aid as the two nations fell short of being democracies.

Miller’s independence did not save him from another defeat in 1948, this time by future Connecticut Governor, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, and Senator Abe Ribicoff. Despite his record of being in and out of Congress, Miller ran ahead of most Republicans (Congressional Record, 16000). This highlighted both how difficult his district had become for Republicans but also to Miller’s appeal. Ideologically, his DW-Nominate score was a 0.062, highlighting his strong independence from party line and his score from the liberal Americans for Democratic Action, which accounted for his last term, was a 32%.

Perhaps had his health allowed it, he would have made another go for Congress. However, Miller developed a kidney ailment in March 1949 that resulted in him being bedridden for a year (The Hartford Courant). Although it looked like earlier in the year he might have been on the mend, he died only weeks after the 1950 election on November 22nd. The Hartford Courant memorialized him thusly, “Former Congressman William J. Miller attained a remarkable degree of success despite a physical handicap that would have discouraged a less courageous man…Bill Miller wore nobody’s collar when he was in Congress. When he thought his party’s leadership was wrong, he voted as his conscience dictated” (Congressional Record, 16000). Despite living a physically difficult and short life, Miller made the best of it that he could and did so with a smile on his face. Republicans didn’t fare well in the Hartford-based district after Miller’s exit, with the Republicans only winning back the district one more time; in 1956, when President Eisenhower was overwhelmingly reelected and the seat was open. It also happened to be the last time Connecticut elected an entirely Republican delegation to Congress. The 1958 midterms resulted in a full switch of the House delegation from Republican to Democrat and saw Republican Senator William Purtell’s reelection loss to Thomas J. Dodd. Could a Republican like Miller be elected in any district in Connecticut today? Perhaps in the 4th or 5th districts, but Connecticut hasn’t sent a Republican to Congress since 2006, and that was Chris Shays, considered one of the most liberal Republicans in his day who fell in 2008 to the district’s current representative, Jim Himes.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Congressional Record. (1950, November 30). U.S. Government Publishing Office.

Retrieved from

Miller, Recovering From Illness, Is Allowed Outdoors. (1950, March 14). The Hartford Courant.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/369901384/

Miller, William Jennings. Voteview.

Retrieved fromhttps://voteview.com/person/6518/william-jennings-miller