Tariffs have been figuring strongly in recent politics thanks to President Trump’s repeated changes in course throughout the year on the imposition or removal of tariffs and certain decisions surrounding them that have been questionable at best. Trump’s policies on tariffs, although more erratic than Republicans of past, given his positive mention of William McKinley does make me think of the McKinley Tariff of 1890, which was at the time a crowning partisan achievement of the GOP and one that helped bring about swift political consequences.

The 1888 election was very close, but a great success for the Republican Party. For the first time since the Grant Administration, they had achieved unified government, and under the highly capable Speaker Thomas Brackett Reed of Maine, they sought to make the most of it. At the forefront of the agenda was the bread and butter of economic Republicanism of the time…protective tariffs. Leading this charge was the popular Representative William McKinley (R-Ohio), known as the “Napoleon of Protection” for his strong advocacy. The Republican Party was at the time strongly unified behind increasing tariffs while the Democratic Party was just as if not more strongly unified against.

A key concept introduced by this legislation was the reciprocal tariff or empowering the executive to raise tariffs on commodities after their addition to the free list to disincentivize other nations from raising their tariffs on these goods. Furthermore, Harrison persuaded the Senate to adopt a provision permitting the president to sign agreements opening foreign markets (U.S. House). These provisions would be upheld unanimously by the Supreme Court as a constitutionally permissible delegation of power in the 1892 decision Field v. Clark.

The initial version of the McKinley Tariff passed 164-142 on May 21st on a highly partisan vote as only three representatives defected: Republicans Hamilton Coleman of Louisiana and Oscar Gifford of South Dakota and Democrat Charles Gibson of Maryland. In the Senate, the bill was managed by Nelson Aldrich (R-R.I.), perhaps the foremost representative of industry in the Senate. On tariffs, in which 138 votes on the subject were held that covered numerous commodities from salt to sponges, the Senate passed the bill 40-29 on September 10th a completely partisan vote. However, there were differences between the House and Senate versions and thus the measure went to conference to resolve them. On September 27th, the House voted on the conference report, which was passed 151-81, with only Republicans Harrison Kelley of Kansas and again Coleman of Louisiana breaking with party. In the Senate, however, there was some more dissent among Republicans, with Senators Preston Plumb of Kansas, Algernon Paddock of Nebraska, and Richard Pettigrew of South Dakota voting against. In its’ final form, this law raised tariffs on average from 38% to 49.5%. Certain commodities were heavily focused on for protective tariffs like manufactured goods such as tin plates to appeal to factories in the East, while wool was jacked up to appeal to the sheep farmers of the rural West. Other tariffs, however, were removed, such as those on sugar, molasses, coffee, tea, and hides, but the president was authorized to raise them should other nations choose to impose on these goods for the United States.

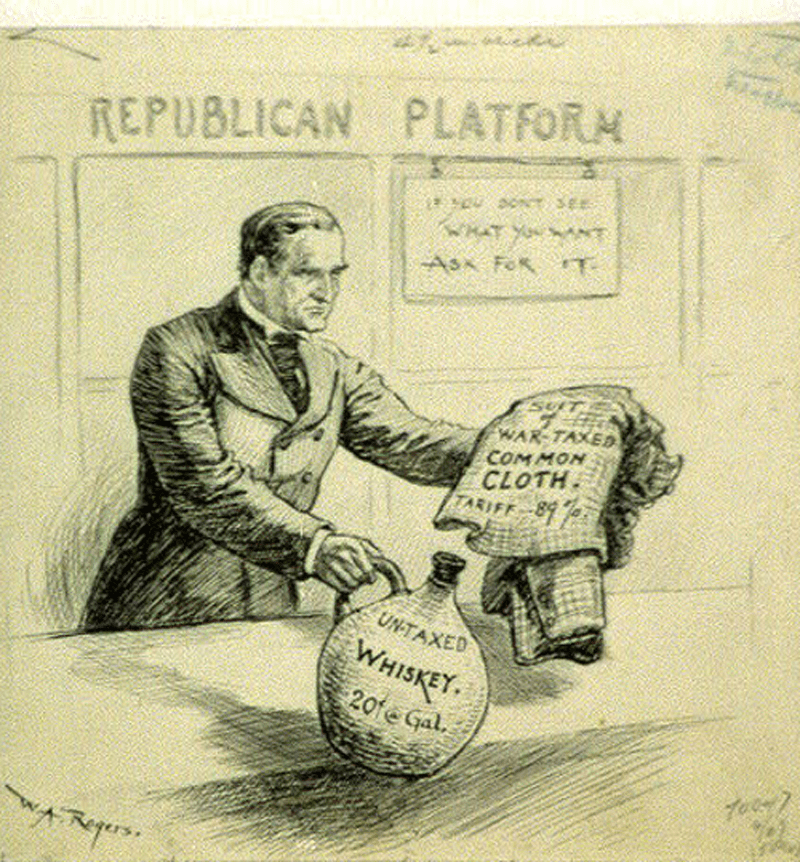

Puck cartoon mocking McKinley.

Although quite the achievement for the Republican Congress, it went into effect on October 6th, less than a month before the 1890 election, and prices promptly rose in response to the tariffs. The Democratic newspaper skewered the bill, and since the benefits of the tariffs (increase in domestic worker wages and jobs) had little time to take effect while the negative side took effect promptly, this resulted in a surge of disapproval of the Republicans. Eleven days after the tariff took effect, The Cleveland Plain Dealer (1890) wrote, “The consumers are finding out that they are compelled to pay the tax, and that fact will grow daily more apparent. A gentleman walked into a hardware store a few days ago and asked to see some pocketknives. A number were placed upon the show case and prices were given. “Are these McKinley prices?” he inquired. “No,” said the clerk, “but we will be compelled to raise prices. We have been busy and have not made any change in our prices yet, but we shall soon do so.” This is only one of many occurrences of which one hears on the streets, and to offset it all there is nothing but prattle about imaginary tin plate factories and other McKinley air castles”. Such unpopularity contributed a great deal to the utter slaughter the Republicans faced in the 1890 midterms including McKinley himself losing his seat, although his loss was in good part due to unfavorable redistricting. Democrats won the popular vote by 8 points in the House, which produced a gain of 86 seats for them and Republicans sustained a 93 seat loss; they also lost seats to the newly formed Populist Party. The Indianapolis Journal (1890), contrary to The Cleveland Plain Dealer, wrote in defense of the tariffs after the election, attributing much of the unpopularity to “falsehoods” propounded about the McKinley Tariff by the “importers’ press”, for instance attributing a price increase in fruits and vegetables to tariffs without mentioning that there were crop failures that produced shortages. Although Republicans continued to be for higher tariffs, they sought to proceed more carefully in the future than they had in 1890, and McKinley would have an astounding comeback, being elected Ohio’s governor in 1891, be reelected in 1893, and then be elected president in 1896. Although a high tariff man, he would embrace the idea of reciprocal tariff reductions, and the Dingley Tariff Act of 1897, although it enacted the highest tariffs on average in American history, would contain a provision permitting the president to reduce duties by up to 20%. McKinley even came around to the idea of reciprocal trade treaties shortly before his assassination.

References

Gould, L.L. William McKinley: Domestic Affairs. UVA Miller Center.

Retrieved from

https://millercenter.org/president/mckinley/domestic-affairs

The McKinley Tariff of 1890. U.S. House of Representatives.

Retrieved from

https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1851-1900/The-McKinley-Tariff-of-1890/

The Victory of Misrepresentation. (1890, November 7). The Indianapolis Journal, 4.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/321737007/

To Adopt the Report of Comm. on Conference on Bill H.R. 9416. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/51-1/h414

To Agree to the Conference Report on H.R. 9416 (26 STAT. 567, 10/1/1890), a Bill Reducing the Revenue and Equalizing Duties on Imports. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/51-1/s383

To Pass Bill H.R. 9416. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/51-1/h184

To Pass H.R. 9416. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/51-1/s364

Up Go the Prices. (1890, October 17). The Cleveland Plain Dealer, 8.

Retrieved from