The history of Congressional pushback against the Supreme Court for taking the side of the federal government over the states has a much more significant history than simply beginning with the Southern reaction to Brown v. Board of Education (1954). It was also the Supreme Court’s rulings that brought on the Tidelands Controversy after the discovery of oil off the California coast, the Supreme Court hindering the ability of states to enact anti-subversive laws, and it was a Supreme Court decision that resulted in Congress affirming insurance regulation as a state function.

In 1942, the Justice Department sued the South-Eastern Underwriters Association, a group of fire insurance companies in six Southern states, for allegedly being in violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. The South-Eastern Underwriters Association contested the suit on the grounds that insurance did not fall under federal jurisdiction, and they seemed to have a solid precedent to cite in Paul v. Virginia (1869), in which the court unanimously ruled that insurance regulation was the purview of the states. As the case was pending, 35 state attorney generals announced their opposition to insurance being under federal jurisdiction (Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, 1). This was a different Supreme Court, however, and it ruled 4-3 in United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters Association (1944) that the insurance industry was covered by the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 as they found insurance to be a form of interstate commerce. This overruled the Supreme Court precedent of Paul v. Virginia (1869), which ruled insurance was not interstate commerce and thus its regulation was the jurisdiction of the states. This decision was yet another Supreme Court move in maximizing what was interpreted as interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause. The Supreme Court had in 1942 gone rather far with the interpretation in Wickard v. Filburn (1942) when they ruled that even activities that have indirect impact on interstate commerce count as interstate commerce. The insurance decision attracted widespread opposition in Congress.

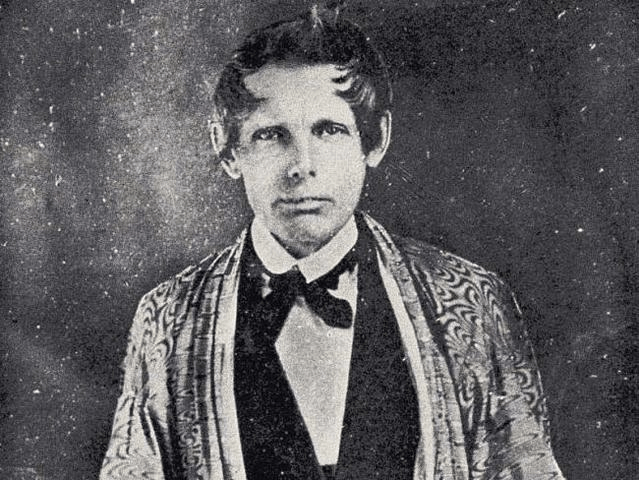

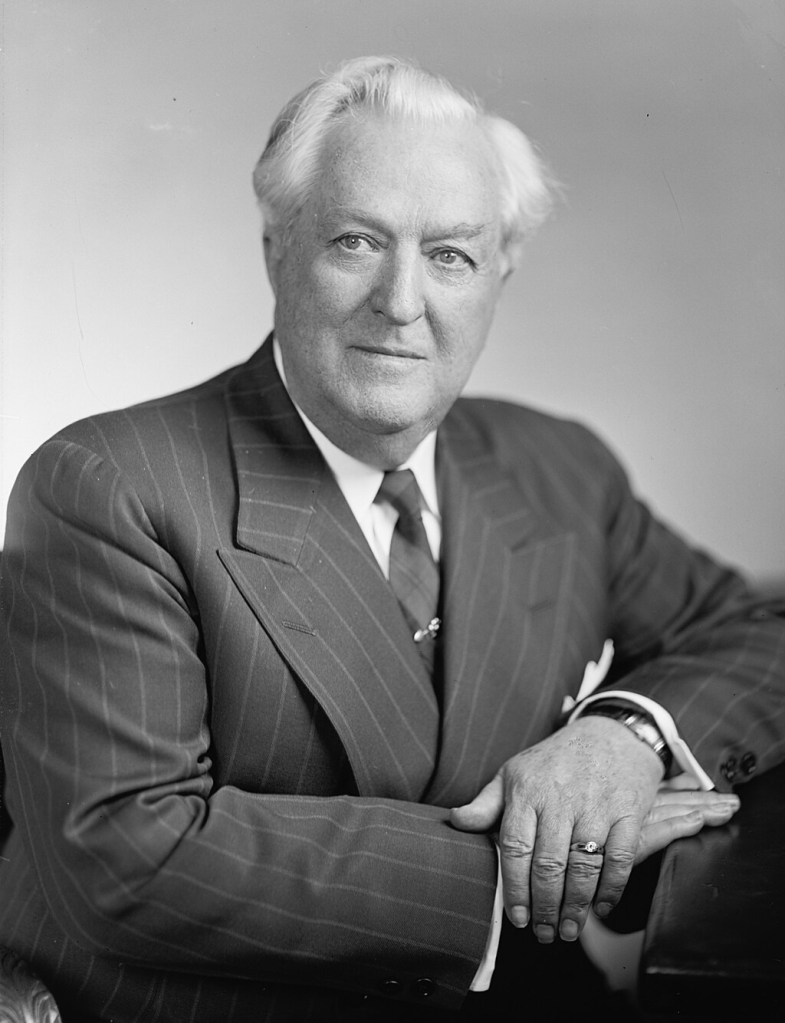

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Hatton W. Sumners (D-Tex.) stated, “I do not propose to yield to the Supreme Court and destroy the greatest democracy in the world…I call upon Congress to assume its responsibility” and Representative Walter C. Ploeser (R-Mo.) charged that “power-hungry politicians” were trying to control the insurance business and that it would fall under the regulatory burdens of the Office of Price Administration (Springfield Weekly Republican, 6). Representative Francis Walter (D-Penn.) sponsored House Resolution 422 in response, which would make clear the Congressional intent that insurance be regulated by states. He condemned the court as having not only overturned a 75-year precedent but also having “contemptuously ignored the intent of Congress” and asserted that the insurance companies had been following the laws of their states (Springfield Weekly Republican, 6). There were, however, representatives who defended the Supreme Court’s ruling in Emanuel Celler (D-N.Y.) and Jerry Voorhis (D-Calif.). They expressed opposition to Congress undoing a Supreme Court ruling and Celler held that proponents of this measure were portraying the insurance industry as “pure as the driven snow” and accused insurance companies of playing a “heads I win, tails you lose” game with rate-fixing under federal and state regulations (Springfield Weekly Republican, 6).

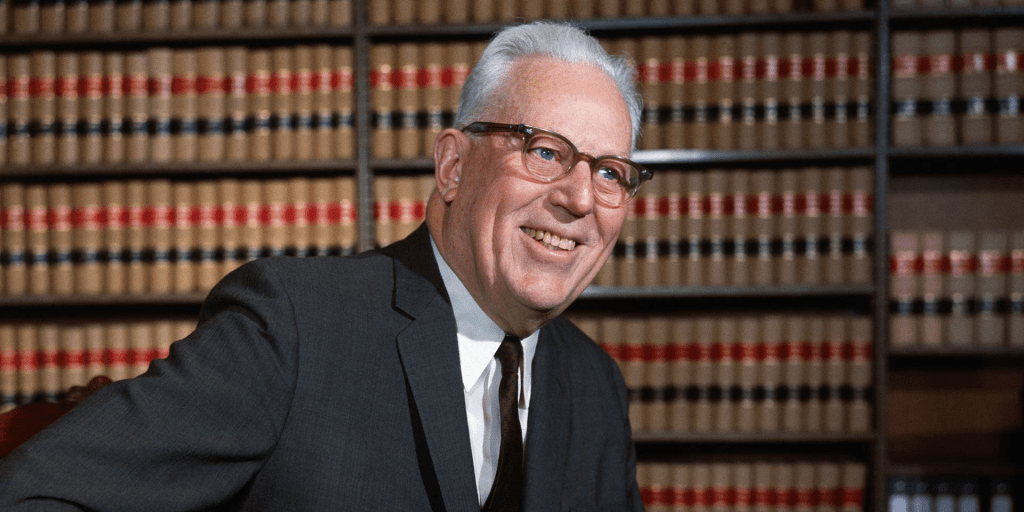

On June 22, 1944, the House passed Walter’s resolution by a vote of 283-54 (D 118-51; R 165-1; P 0-1; AL 0-1). The Roosevelt Administration opposed efforts against this decision, but Congress was in an increasingly rebellious mood, evidenced by them overriding his vetoes of the Smith-Connally Act in 1943 and the Revenue Act of 1944, the latter the first time Congress ever overrode a presidential veto of tax legislation. However, the measure didn’t advance to the Senate that year, and the bill would have to wait until the next session. This bill, sponsored by Senators Pat McCarran (D-Nev.) and Homer Ferguson (R-Mich.) was one of the first priorities of the 79th Congress, and it again passed on a strong bipartisan basis, 315-58 (D 150-56; R 165-0; P 0-1; AL 0-1) on February 14, 1945. The Senate followed up two weeks later, passing the bill 68-8 (D 35-8; R 31-0; P 1-0) on February 28th. The vote far beyond the margin of President Roosevelt to veto, he signed the measure into law on March 9th. Interestingly, there was a revision to this law in recent years. In 2020, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Competitive Health Insurance Reform Act that subjected medical and dental insurance to federal anti-trust regulations in response to rising healthcare costs, and it was signed by President Trump on January 13, 2021.

P.S.: My 2022 content is going to be archived come Tuesday.

References

House Exempts Insurance Firms. (1944, June 29). Springfield Weekly Republican, 6.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/1065371041/

Insurance Regulation Opposed By 34 States. (1944, January 10). Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, 1.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/116466917/

Paul v. Virginia, 65 U.S. 168 (1869).

Retrieved from

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/75/168/

S 340. Express the Intent of the Congress with Reference to the Regulation of the Business of Insurance. On Passage. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/79-1945/h9

S 340. Express the Intent of the Congress with Reference to the Regulation of the Business of Insurance. Adoption of Conference Report. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/79-1945/s7

To Recommit H. Res. 422, Affirming the Intent of Congress That Regulation of Insurance Business Stay Under State Control [Passage]. Govtrack.

Retrieved from

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/78-1944/h145

United States v. South-Eastern Underwriters, 322 U.S. 533 (1944).

Retrieved from

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/322/533/

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. 111 (1942).

Retrieved from