When it comes to conservatism, one state we don’t think of so much these days is Illinois. It is difficult for Republicans to win statewide thanks to Chicago, which has been unshakably Democratic since the days of Mayor Richard Daley, and Democratic politics seem to have, at least at the moment, an iron-clad grip. One figure who would be tremendously out of place in the modern politics of Illinois was Noah Morgan Mason (1882-1965).

The 12th of 13 children of a working-class family in Glamorganshire, Wales, the family immigrated to the United States when Mason was 6. Although he had to drop out of school to work on the family farm at 14, his mother saw something in the young boy that told her that he was destined for a greater future than his father, and thus she pushed him to go to college, and he did, graduating from Illinois State Normal University. Mason would dedicate himself to education, and at 22 he was the principal of Jones School in Oglesby, serving for five years, after which he became the city’s school superintendent (Hill). This prominent role led him to politics, and in 1919 he ran for and won the post of city commissioner for Oglesby. In 1926, Mason tried for the first time to win a seat in the Illinois State Senate but lost. However, this would be the only race he ever lost, and he would be elected to the State Senate in 1930.

As a state senator, Mason voted to repeal Prohibition. Although he had time and again expressed his personal opposition to drinking, he recognized that a majority of his district had voted for a referendum to repeal Prohibition, and he believed that he should abide by the wishes of his constituents in what he regarded as the Jeffersonian and Lincolnian tradition (Hill). Indeed, Mason was attentive to the wants and interests of his conservative constituency, and it kept him in office, but higher office was on his mind.

His opportunity for higher office came in 1936, as Congressman John T. Buckbee was ailing. When talk of Mason running to succeed him came about, he denied that he would seek the office unless Buckbee decided to retire due to ill health (Hill). This showed respect for the ill incumbent, and Mason would win the nomination to succeed him after he died in office. Although the 1936 election would elevate Democrats to the height of their power, Mason won his election too, and he presented quite an alternative.

Mason vs. The New Deal

From the very start of his Congressional career, he made his position clear as a committed conservative with his maiden speech to the House focusing against the expansion of the Federal government and in opposition to President Roosevelt’s “court packing plan” (Samosky, 36). Although solidly conservative in his record from the start, he was not necessarily averse to compromise. For instance, Mason, along with all but one of Illinois’ representatives, voted for the Wagner-Steagall Housing Act in 1937 while a majority of House Republicans voted against. He also voted for the original House passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act while opposing the final version. Mason would oppose work relief measures as well, and saw the work relief program as a corrupt way to strengthen the power of the Democratic Party. He accused its director, Harry Hopkins, of having transformed the program into “the most powerful political instrument of partisan advantage ever devised in the United States of America” and would in 1944 accuse him of condoning or encouraging “intimidation, bribery, and wanton violation of the Corrupt Practices Act” (Hill). Mason also condemned numerous Brain Trusters for radical backgrounds and statements. He regarded guaranteed minimum income, employment for all by the government, and confiscation of all property except houses and subsistence farms as “State socialism”, comparing such ideas to the practices of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Soviet Russia (Samosky, 41). Although Mason represented a rural district, he stood opposed to New Deal agricultural policy, which he saw as heavy on government control. He instead advocated the adoption of the McNary-Haugen measure that the farm bloc had attempted to pass in the 1920s over the opposition of President Calvin Coolidge (Samosky, 36).

Although strongly opposed to the New Deal’s political machinery, domestic spending, strong hand on businesses, ever-expanding Federal government, the infiltration of the government by Communists, and organized labor policies, he did not only see the bad in the New Deal. In January 1944, he stated that he considered the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Social Security, and the Fair Labor Standards Act to have been overall positive albeit flawed (Samosky, 42). Mason was, however, unconditionally opposed the Office of Price Administration during World War II and was against the price, wage, and rent controls established. He held that “Rationing merely distributes scarcity” and opposed economic controls as he saw them as hindering personal initiative (Samosky, 36). Mason would be similarly opposed to President Truman’s Fair Deal as he was Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Mason vs. Foreign Aid

Noah Mason’s stances on foreign policy would strike many as parochial. He was not only opposed, as were a majority of Republicans, to FDR’s foreign policy before World War II, he also opposed the bipartisan foreign policy consensus after World War II. Although Mason seemed to support the idea of an international peacekeeping body in theory given his vote for the 1943 Fulbright Resolution, in practice he was against, as he was one of 15 representatives to vote against the United Nations Participation Act in 1945. Given this vote, he certainly could not have been counted on to vote for aid to Greece and Turkey in 1947 or the Marshall Plan in 1948, and he didn’t. Mason did not ease up on his opposition to foreign aid during the Eisenhower Administration, and if anything, his opposition got stronger. He could not be counted on to support any elements of Eisenhower’s agenda that were moderate or liberal. Mason considered foreign aid to be a grand giveaway that added to the national debt and thus added to how much Americans would have to be taxed in the future, stating that it “shunted off upon our children a debt of $300 billion – a greater debt than all the other countries in the world combined” (Samosky, 48). Despite Mason being an outsider on many issues, his Illinois constituency appeared to be content with his stances, as they kept reelecting him.

Mason vs. Subversion

Noah Mason was a strong foe of radical forces that pushed discordance in society and government. In 1938, he made a speech to La Salle, Illinois’ Elks Club in which he condemned organizations such as the Silver Shirts, the Ku Klux Klan, and the German American Bund for stirring up racial and religious hatred as well as Communists and individuals in government he regarded as pushing class hatred (Samosky, 44). Fittingly, Mason was placed on the House Committee on Un-American Activities (The Dies Committee) in that year, serving in this post until 1943, and he would vote to make the committee permanent in 1945. He was a reliable vote for most measures intended to curb subversion. However, Mason made an interesting exception when on April 8, 1954 he voted to require a Federal court order for a wiretap in national security cases, contrary to the position of the Eisenhower Administration. He also praised Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.) as a “fighting Irishman” and a “red-blooded, two fisted American” (Samosky, 45).

Mason: For and vs. Eisenhower

President Eisenhower and his greatest backers were what were known as “modern Republicans”, in other words, accepting of the continuance of much of the New Deal with more fiscal discipline, for foreign aid, and easing up on protectionism. Mason was no such figure. He consistently opposed foreign aid bills, opposed federal aid to education, was one of 35 representatives to oppose a reciprocal trade bill in 1953, and opposed a bipartisan bill that year admitting more European refugees. Although born in Wales into a working-class family, Mason was for strong immigration limits, stating, “We’ve got to keep America American” (Alsop, J. & Alsop, S.). He saw restricting immigration as a way of protecting American values from potentially subversive influences, and saw his role as one of a preserver of the values that resulted in the flourishing of the United States. As a member of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, Mason sought to overhaul the tax code. As journalists Joseph and Stewart Alsop (1953) reported, he said that he wanted to “relieve the overtaxed by taxing the untaxed”, which meant per the Alsops “reducing income and corporate taxes, while levying a manufacturer’s sales tax, taxing co-operatives, and depriving the churches, charitable foundations and universities of most of their existing exemptions”. Eisenhower by contrast wanted an extension of the excess profits tax, which of course Mason was completely opposed to.

As journalists Joseph and Stewart Alsop (1953) noted in their article on him as an example of difficulties President Eisenhower was having with the conservative wing of the GOP, “President Eisenhower’s problem with his own party is agreeably symbolized by Noah Mason…” and concluded with, “…the question remains – and it is pressing question – whose party is it, Noah Mason’s or Dwight Eisenhower’s?” He would, however, vote to sustain Eisenhower’s cost-conscious vetoes. Mason also maintained a strong devotion to a conservative view of Federalism. This meant that the Federal role was to be as limited as he saw fit under the Constitution, and this perspective translated into his positions on civil rights.

Mason vs. Civil Rights

Among House Republicans, by the Eisenhower Administration he was one of the most unbending opponents of civil rights legislation. Mason voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, which were watered-down, and no Senate Republicans had opposed, and was one of nine Republicans to vote against even considering the latter bill. He hadn’t opposed all civil rights proposals in the past, indeed in 1937 and 1940 he had voted for anti-lynching legislation, and he had voted for unsuccessful Powell Amendments in 1946 and 1956 to counter segregation in public education. He also had accepted the premise that non-discrimination by government and in societal opportunities was a good as posited by President Truman (Samosky, 39). However, what he opposed outweighed what he supported considerably. Mason opposed four of five measures against the poll tax he registered a vote or opinion on. This included the 1962 CQ Almanac recording that he had either announced or answered a CQ poll that he was against the 24th Amendment. He also opposed Fair Employment Practices legislation and opposed the 1960 Powell Amendment to counter segregation in education. During the debate over the 1957 Civil Rights Act, Mason contended that “each and every” right was “a State function, a State responsibility, a State obligation” and was “definitely left to the States by the Constitution” (Samosky, 39). He further delivered a speech before Congress in which he connected Federal civil rights legislation to the New Deal’s Federal intervention into the business of States. He painted a happy picture of the United States in this speech, that is, until in “…came our New Dealers, our Fair Dealers and our Modern Republicans with ideas and proposals to change our constitutional form of government into a welfare state, a centralized Socialist-Labor government, without our sovereign States relegated to a subservient position, exercising only those powers and duties that might be assigned them by an all-powerful, arrogant, dictatorial, centralized Federal Government – divorced from those powers, duties, and privileges guaranteed to the State by Our Federal Constitution” (Mason). Mason had no personal love for segregation, but he saw civil rights legislation as supported by the Eisenhower Administration as yet another manifestation of this trend he speaks against. This was not the only way that he could be in the minority of his party. He was also one of 24 House Republicans to vote against the admission of Hawaii in 1959. Although not a civil rights measure itself, the admission of Hawaii as well as Alaska added four pro-civil rights senators, thus many Southerners were in opposition. Indeed, if a bill was passed with but a small contingent of opposition from the right, Mason was likely to be among the dissenters.

Mason vs. the Majority

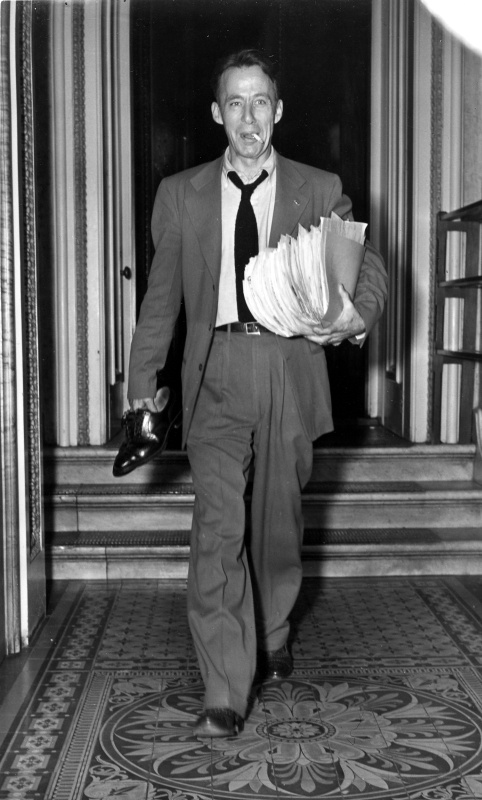

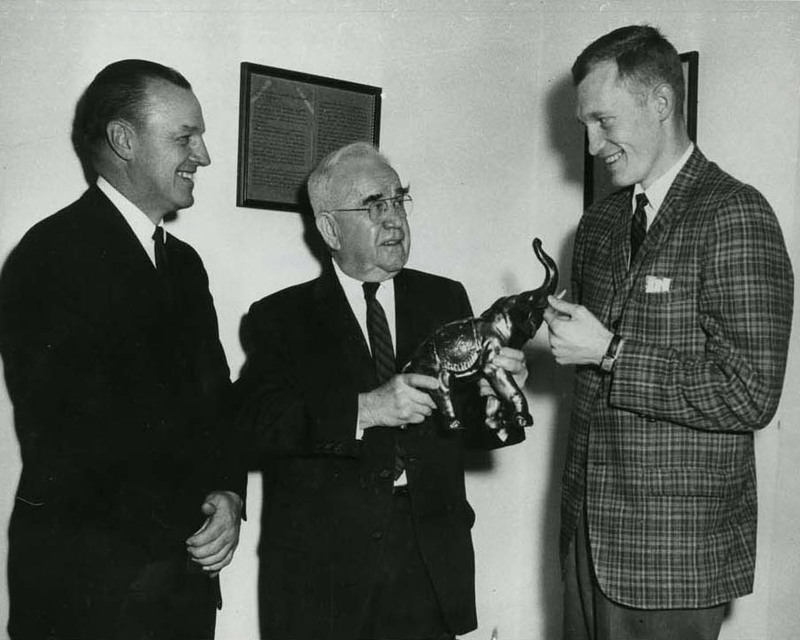

Image from Chronicling Illinois, citation in References.

Given that he rarely compromised in his views, especially in his later years, Mason could often be found against the majority on legislation, especially since he was one of the most conservative people in the Republican Party, which during his time in Congress only had a majority in two sessions. Some votes in which Mason was desperately in the minority aside from previously mentioned legislation included:

. On April 19, 1944 he voted against extending the Lend-Lease Act one year, which was passed 334-21.

. He voted for the Rankin (D-Miss.) motion to defeat the entire bill extending the Office of Price Administration, which would have killed all controls, and was defeated 20-370 on April 18, 1946.

. On July 18, 1955, he voted against an expansion of Social Security benefits, which passed 372-31.

. On July 20, 1955, he voted against increasing the minimum wage from 75 cents to $1 an hour with no coverage expansions, which passed 362-54.

. On August 26, 1960, he paired against the Kerr-Mills Act, a popular substitute for proposed Medicare legislation which provided Federal funds to States for medical costs of poor elderly people, which passed 369-17.

. On April 20, 1961, he paired against increasing Social Security benefits, the measure passing the House 400-14 on April 20, 1961.

. On June 6, 1962, he voted against a school lunch bill that passed 370-11.

. On September 24, 1962, he voted against authorizing President Kennedy to mobilize 150,000 reserve troops in response to increasing Soviet presence and armaments in Cuba, which passed 342-13.

However, something that should be noted about Mason was that despite his extreme views, he was a personable communicator of them and liked by his colleagues. Indeed, he was known to be a good-natured and friendly figure. Perhaps you could call him a happy warrior. In 1955, the New York Times characterized him as a “white-haired, genial battler” (Samosky, 39). Indeed, given how much Noah Mason opposed legislation just generally, I think an appropriate characterization for him is the “Amiable No-Man”. And he would be saying no a lot to the last president he served with.

Mason vs. The Kennedy Administration

Unsurprisingly, Noah Mason was opposed to almost every aspect of John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier, from public works legislation to the Peace Corps. However, he made one notable exception, and it was perhaps based on his background as an educator. Mason voted for the bill providing a five-year program for Federal aid to States for educational television in 1962. His most notable and final battle was that year and it was on a subject that he never compromised on…trade.

Noah Mason was consistently and unalterably protectionist in his views on trade, and expressed such views on the House Ways and Means Committee and cast such votes. In 1962, he waged his last major battle in Congress against the Kennedy Administration’s Trade Expansion Act, which granted the president more authority to negotiate mutual tariff reductions of up to 50% and to aid workers harmed by such reductions by more generous unemployment benefits among other measures (CQ Almanac). He motioned to recommit the bill to substitute it with a one-year extension of the existing Trade Agreements Act, which was defeated 171-253 on June 28th, and the Trade Expansion Act was signed into law. That year, Mason announced that he would not be up for another term, and told the House in his speech that “I plan to become a missionary to the liberal heathen on the Hill…preaching the gospel of conservatism to those who will listen. They may yet be saved to a happier future in which taxes will go down and not always up; in which the national debt will grow smaller and not bigger, in which the army of bureaucrats will get their proper comeuppance” (Hill). The latter part of this statement makes me think he would have certainly approved of the discharges of Federal employees that have occurred lately. Mason’s career, at least the last six years of it, was seen as incredibly positive by conservatives, with him agreeing with Americans for Constitutional Action 97% of the time, only differing with them on a vote to retain the Soil Bank Program in 1957 and on the aforementioned educational television legislation. By contrast, he only agreed with Americans for Democratic Action, which judged his record from 1947 to 1962, 7% of the time. Mason’s DW-Nominate score was a 0.63, which placed him consistently among the top ten most conservative members of the House in his time.

The conservative revival that Mason had been hopeful for would have to wait until after his death, as he lived only two years after his retirement, dying on March 29, 1965, of heart failure, a year that perhaps was the apex of American liberalism in the 20th century. I cannot imagine that he would have supported the legislation enacted later in the year, including the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Voting Rights Act, and Medicare. Surely, he would have been heartened had he lived to see the rise of Reagan, even if he probably would have been disappointed with the budget deficits. Perhaps Mason is from the great beyond disappointed in where Illinois has gone, with a mere 3 of 17 representatives being Republicans thanks to redistricting, and even his old district is now represented by Democrat Lauren Underwood. He would certainly, however, be more heartened by the Republicans are they are today, as the party, 72 years after the Alsop brothers asked the critical question of whose party it was, it is clearly more of Mason’s today than Eisenhower’s.

References

Alsop, J., & Alsop, S. (1953, June 30). Mason Symbolizes Ike’s Problem. St. Petersburg Times.

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Hill, R. Noah Mason of Illinois. The Knoxville Focus.

Retrieved from

https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/this-weeks-focus/noah-mason-of-illinois/

House Increases Bank Building Fund; Approves Constitutional Amendment Banning Poll Tax; Clears Satellite Corporation Bill. (1962). 1962 CQ Almanac, 630-631. Congressional Quarterly.

Retrieved from

Howard Mullins, Noah M. Mason, and Fred Dickey. Chronicling Illinois.

Retrieved from

https://www.chroniclingillinois.org/items/show/29748

Mason, Noah Morgan. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/6061/noah-morgan-mason

Mason Offers Valedictory To Congress. (1962, July 18). Belleville News-Democrat, 13.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/766382976/

Northerner Backs the South – States’ Rights and the U.S. Constitution Versus Civil Rights and the Court. (1957, June 7). The Times (Shreveport, LA), p. 15.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/211437254/

Samosky, J.A. (1983). Congressman Noah Morgan Mason, Illinois’ Conservative Spokesman. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 76(1), 35-48.

Retrieved from

http://www.idaillinois.org/digital/collection/eiu02/id/1216/

The Trade Expansion Act. CQ Almanac.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal62-1326212#_=_