When we talk about the “party switch” it is very important that we realize what this means, lest we think this means that the parties switched left-right ideologies, or that everything switched in 1964. It means a gradual shift in political philosophy in demographics and regions. Mississippi at one time elected liberal populists such as James K. Vardaman and Theodore Bilbo, men who were committed to white supremacy as well as taking on big businesses and helping poor whites. The career of William Meyers Colmer (pronounced “Calmer”) (1890-1980) is a prime example of the shift of politics in Mississippi and the Deep South as a whole. He was in Congress from the Roosevelt to Nixon Administrations, and the Colmer of 1972 seemed to bear little resemblance to the Colmer of 1932. Indeed, when he was elected in the Roosevelt wave, he was a New Dealer. Mississippi at the time was enamored with FDR, and one of its senators, Pat Harrison, was a key supporter of his first term agenda. Later in life, Colmer readily acknowledged the contrast of his earlier years, telling a friend, “You may not believe it, but I came to Washington as something of a liberal” (Hill). Although even in the first Congress of the Roosevelt Administration there was some foreshadowing of the state’s future with three members of Mississippi’s delegation voting against the National Industrial Recovery Act, Colmer was not among those representatives; he was on board with most of FDR’s agenda, and was the only representative from Mississippi to support the Bituminous Coal Act in 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938 (minimum wage). He would also, like most Southerners, be supportive of FDR’s foreign policies.

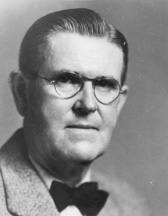

Colmer in 1940.

In 1939, Colmer was tapped to be on the powerful Rules Committee, but it would not be long before his record would increasingly move towards conservatism. This was in keeping with the increasing conservatism of his district based in Biloxi (Finney). The South overall had come to dislike how strong unions had become since the Wagner Labor Relations Act of 1935 and were strongly opposed to the staunchly left-wing Congress of Industrial Organizations. It certainly didn’t help matters that this union was racially integrated. The last time in which Colmer was sort of cooperative with the national Democratic Party was in the 80th Congress, in which he voted against a good number of Republican-backed positions. But even there, he was far from the strongest of partisans, with him agreeing with the liberal Americans for Democratic Action’s (ADA) positions in 1947 and 1948 73% and 55% of the time respectively. In 1947, Colmer ran for the Senate to succeed the late Theodore Bilbo, but he was defeated by John C. Stennis and did not try to move up again. After the 1948 election, in which he backed the State’s Rights Party (Dixiecrats) he would be among the most dissenting of Democrats within the party with low ADA scores.

Colmer played a key role in the consideration of legislation in the Rules Committee, which from 1955 to 1967 was chaired by fellow conservative Democrat Howard W. Smith of Virginia, who was a master obstructionist. Liberal legislation would often die in his committee as he, Colmer, and the four Republicans would vote it down, with the committee getting a 6-6 deadlock. Although he was now conservative on the bulk of issues, he did stick with some of his old New Deal positions on agriculture and public power. He opposed efforts by the Eisenhower Administration to institute flexible price floors on agriculture as opposed to rigid and high price floors, and opposed efforts to curb the Tennessee Valley Authority. Colmer was, consistent with the sort of politician his state would elect at the time, a segregationist who signed the Southern Manifesto against school desegregation and opposed all civil rights measures of the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Despite this, Colmer was not a racial demagogue and prided himself on having “never made an anti-Negro speech in my life” (The New York Times, 1961). In 1960, Colmer sided with his state in supporting the candidacy of Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia for president, much to the consternation of Democratic leadership as well as many of his fellow Southerners who had stuck their necks out for Kennedy (Finney). This was the second time he had bucked the national Democrats and it threatened to complicate things for Colmer as Kennedy won the election. The following year, Speaker Sam Rayburn (D-Tex.) made his displeasure with Colmer clear and let it be known that he thought of him as “a very inferior man” (Finney). Rayburn attempted, without success, to get Colmer reassigned. What ended up happening was that the Rules Committee was expanded to add two Democrats and one Republican by a vote of 217-212 on January 31st. Although the majority was on paper 8-7 liberal, there were still some defeats that occurred on the Rules Committee as a person or two in the liberal majority would break off. In the next Congress, this expansion was made permanent and was helpful in passing Great Society legislation.

Chairman of the House Rules Committee

In 1966, Chairman Smith lost renomination, and Colmer was next in line. Since he was a think-alike to Smith, liberal Democrats initially thought that his chairmanship of the powerful committee would be like his, but this wasn’t the case. Colmer did not exercise his power further than persuasion through votes to bottle legislation in the committee, and all members appreciated his Southern courtliness and his sense of fair play. This was particularly demonstrated when he made sure that Bella Abuzg (D-N.Y.), very much his political opposite, would get her say in a House debate (Finney).

Mentoring a Prominent Successor and Retirement

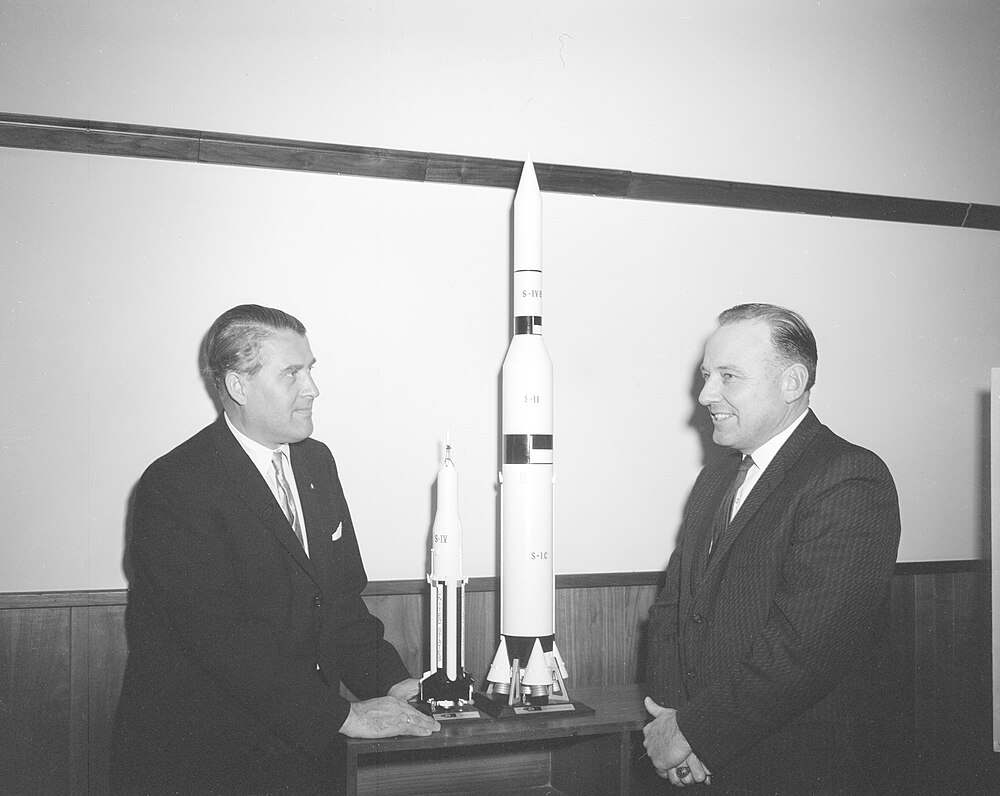

Colmer with Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, April 1971.

In 1968, Colmer hired young lawyer Trent Lott as an administrative assistant, and mentored him in the ways of Washington D.C. to the point that when he decided to call it quits in 1972, he endorsed him as his successor despite him running as a Republican. The party affiliation did not matter for him, as by this time he had been voting with conservative Republicans for many years. It was widely agreed upon that Colmer, at least in his postwar years, was a conservative. He had only sided with ADA 10% of the time from 1947 to 1972 and sided with the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action 86% of the time from 1957 to 1972. Colmer’s DW-Nominate score was a 0.052, which was high for a Democrat. In 1974, Lott would state of his predecessor, “If they’d listened to Bill Colmer 25 years ago, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in today” (Hill). He would reach greater heights in the Republican Party than Colmer had reached as a Democrat, serving as House Minority Whip from 1981 to 1989 and as Senate Majority Leader from 1996 to 2002. However, he would resign from the post in a 2002 controversy regarding a speech he delivered for Strom Thurmond’s 100th birthday, in which he said something similar to what he said in 1974 regarding Colmer. In 1976, Colmer again endorsed a Republican candidate when he supported Gerald Ford for president, holding that he had “moral integrity” while the Democrats were pushing “socialist” ideas (Hill). He was far from the only former Democratic representative from Mississippi to back Ford. His colleagues Thomas Abernethy, Charles H. Griffin, and John Bell Williams did so too (Hill). Colmer’s principal political concern in retirement was inflation. He stated, “I do not think we can go on indefinitely with deficit spending without bringing down the house of inflation on us. We must either stop inflation or we are going to lose our cherished form of government” (Hill). For most of his retirement, Colmer appeared to remain in good health, and his demise was mercifully quick compared to many people, dying only a month after the start of his decline on September 9, 1980 at the age of 90.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Colmer, William Meyers. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/1952/william-meyers-colmer

Finney, J.W. (1972, March 7). The House Traffic Cop William Meyers Colmer. The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Hill, R. (2024). The Gentleman From Mississippi: William M. Colmer. The Knoxville Focus.

Retrieved from

https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/this-weeks-focus/william-m-colmer/

Target for a Purge; William Meyers Colmer. (1961, January 5). The New York Times.

Retrieved from