Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987) was a rather unique woman of many talents. She was a skilled playwright, writer, magazine editor, a politician, and a socialite. Although her life in many ways was that of a feminist, she didn’t always have such a mindset, and her life reflected what can be seen as positive and negative things that people attribute to feminism.

Born Ann Clare Boothe, she had something of a difficult childhood; she was the daughter of a showgirl and her father left the family when she was 8. Her mother had great ambitions for her, and pushed her to be an actress, and appeared in the Broadway play The Dummy in 1914 as well as had a bit part in the film The Heart of a Waif the following year. As a teenager, she gained some notoriety as a suffragist, working for the National Woman’s Party. Her mother, wanting her to climb the social ladder, had arranged her marriage to the clothing heir George Tuttle Brokaw in 1923, who was 24 years her senior. They had one daughter, Ann Clare Brokaw, in 1924. The marriage was, however, unhappy as Brokaw was a violent alcoholic. As she recalled later about the marriage to journalist Dominick Dunne, “I know all about violence and physical abuse because my first husband used to beat me severely when he got drunk. Once, I can remember coming home from a party and walking up our vast marble staircase at the Fifth Avenue house while he was striking me. I thought, if I just gave him one shove down the staircase I would be rid of him forever” (Brenner). Clare asked his mother for a divorce in 1929, and it was granted, with her getting a generous settlement that made her independently wealthy. However, she had to split custody of her daughter with Brokaw for half the year. He would die six years later in a sanitarium, a consequence of his alcoholism.

Clare Boothe would go on to be the caption writer for Vogue magazine in the early 1930s, then became the editor of Vanity Fair. She wrote profiles on people, one of the first being Time and Fortune Magazine’s Henry Luce. She initially despised him, writing, “He claims he has no other interest outside of his work, and that his work fills his waking hours” (Brenner). Nonetheless, in 1935 she would after only a few meetings with him, marry him. Luce had divorced his wife explicitly to marry her. He would subsequently establish Life magazine, reportedly at her suggestion (The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers). Their marriage was not an easy one, but one that lasted. However, it lasted through them having an open marriage, with her having numerous affairs with prominent figures, including Randolph Churchill (Morris, 2014). There was a mutual respect for each other and both elevated the other in different ways. In 1936, Luce wrote the all-female satire The Women in only three days, which became a hit on Broadway. She also wrote Abide with Me (1935), Kiss the Boys Goodbye (1938), Margin for Error (1939), Child of the Morning (1951), and Slam the Door Softly (1970). Luce’s works also include three books, which were Stuffed Shirts (1931), Europe in the Spring (1940), and Saints for Now (1952) (editor). She was also known for her wit. Some quotes attributed to her include:

“Money can’t buy happiness, but it can make you awfully comfortable while you’re being miserable.”

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.”

“Because I am a woman, I must make unusual efforts to succeed. If I fail, no one will say, ‘She doesn’t have what it takes.’ They will say, ‘Women don’t have what it takes.’”

“Censorship, like charity, should begin at home; but unlike charity, it should end there.”

“If God wanted us to think with our wombs, why did he give us a brain?”

“No good deed goes unpunished.”

“Nature abhors a virgin – a frozen asset.”

Luce would also be a war correspondent for Life magazine from 1939 to 1942, and her connections would result in her getting interviews with political and military leaders. She would not hesitate to issue criticism when she thought it worthy. However, Luce did get into some trouble after she mockingly likened RAF pilots to “flying fairies” in print (Morris, 1997, 458).

Politics

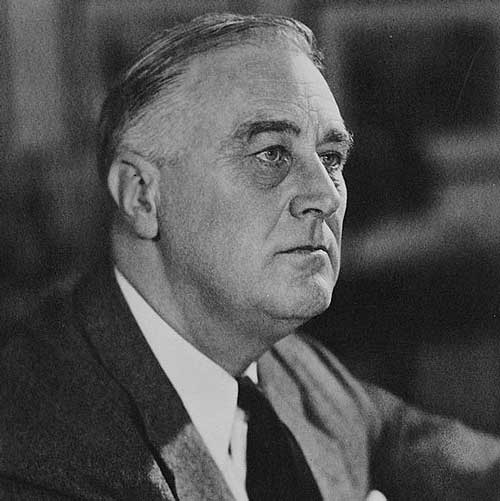

When Luce was in a relationship with Bernard Baruch, she, like him, supported FDR’s election in 1932. However, she became disillusioned with Roosevelt’s economic policies by his second term and switched from Democrat to Republican. In 1940, Luce endorsed and campaigned for Republican Wendell Willkie, opposing FDR not only out of ideological differences but out of a belief that the two-term tradition shouldn’t be broken. Her politics were at this point indeed similar to those of her husband. In 1942, she was recruited to run for Congress. She condemned incumbent Le Roy Downs, who had defeated her stepfather Albert Austin for reelection in 1940, as a “rubber stamp” for Roosevelt (U.S. House). Luce won in the Republican wave, but by a plurality. If the left had lined up behind incumbent Democrat Le Roy Downs, he would have won reelection; 11% of the vote had gone to the Socialist candidate. Luce’s platform was “One, to win the war. Two, to prosecute that war as loyally and effectively as we can as Republicans. Three, to bring about a better world and durable peace, with special attention to postwar security and employment here at home” (U.S. House).

Luce and FDR

Luce was publicly critical of President Roosevelt, and in the 1944 presidential campaign she charged that he was “the only American President who ever lied us into a war because he did not have the political courage to lead us into it” (U.S. House). He didn’t appreciate her barbs and was sure to campaign against her explicitly. Vice President Wallace dismissed her as a “sharp-tongued glamor girl of forty” who when running around the country without a mental protector, “put her dainty foot in her pretty mouth” (U.S. House). However, Luce and FDR were not as far apart on policy as their public relationship would suggest. While she supported overriding President Roosevelt’s vetoes of bills restraining subsidies and providing tax relief, she voted to sustain his veto of the Smith-Connally Act, which was designed to counter wartime strikes. Luce also supported retaining the National Youth Administration in 1943. She opposed increased funding for agricultural programs and supported minor restraints to price control while opposing strong efforts to hinder price controls. Luce was also an internationalist, supporting the creation of an international peacekeeping body after the war’s conclusion, an idea which would become the United Nations. Luce also was opposed to the House Committee on Un-American Activities, voting against funding it in 1943 and opposing making it a permanent committee in 1945. Her DW-Nominate score was a 0.07, making her one of the least conservative Republicans in Congress. In 1943, Luce supported repealing the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was signed into law. She was in favor of eliminating discrimination in immigration, supported desegregation of the army, and supported the Equal Rights Amendment.

Although President Roosevelt had much in good news that year with the defeats of bitter foes Senator Gerald Nye of North Dakota and Representative Hamilton Fish of New York, Luce would win reelection by one point. Like in 1942, if the left had unified behind the Democratic candidate, Luce would have lost. That year, Luce suffered a terrible tragedy when her daughter was killed in a car accident at 19 while attending university. After her daughter’s death, she turned to faith and spiritualism and converted to Catholicism but was never able to persuade her husband to do so.

In 1946, Luce sponsored with Rep. Emanuel Celler (D-N.Y.) a bill permitting naturalization of Indians and Filipinos and permitting a quota of 100 a year from each nation which was signed into law by President Truman. She was also consistently anti-communist in her foreign policy outlook. Luce argued that the Kremlin had “incorporated the Nazi technique of murder” and regarded postwar foreign policy surrounding Poland as “a partition of Poland and overthrow of its friendly, recognized constitutional Government” (U.S. House). In January 1946, she decided not to run for reelection. This farewell from politics would turn out to be temporary, as in 1952 Luce energetically campaigned for the election of Dwight Eisenhower. The following year, Eisenhower saw her as a perfect candidate to represent the United States in Italy, and nominated her ambassador. Although more conservative Italians were initially a bit put out that Eisenhower had picked a woman, in a week’s time she had won them over. This post was particularly important in the Cold War context as although Italy was on the Allied bloc, they had one of the strongest communist parties in Western Europe, and there was always a risk of a communist victory. During this time, Luce was able to negotiate a border dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia. She served in this capacity until 1956, by which time she had become very ill. This illness had started in 1954, and after she was taken back to the United States, it was found that she had been suffering from arsenic poisoning. It turned out that the arsenic paint on the ceiling of her bedroom was flaking off. By 1959, Luce had recovered and although she was confirmed Ambassador to Brazil, she miscalculated when she said just after her confirmation “my difficulties, of course, go some years back and began when Sen. Morse was kicked in the head by a horse” (McMillan). This referenced a 1951 incident in which a horse broke Morse’s jaw. The controversy that arose resulted in her resignation only three days later.

In 1964, Luce, who had become increasingly conservative over the years, briefly considered reentering politics to run for the Senate in 1964 as a member of New York’s Conservative Party, but dropped the idea. That election would be won by none other than Robert F. Kennedy. That year, Luce firmly backed Senator Barry Goldwater (R-Ariz.) for the presidency. Her husband, Henry Luce, was increasingly in poor health, and on February 28, 1967, he died of a heart attack. Afterwards, Luce moved to Hawaii where she was a prominent socialite. In 1973, President Nixon appointed her to the Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, where she served until 1977. President Reagan reappointed her in 1982, and she served until her death. In 1983, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Luce could be quite a story-teller, and this included some fiction. According to Marie Brenner (1988), she had told friends in the past that numerous prominent men had wanted to marry her and that she had slept with Strom Thurmond. Although many people would regard Clare Boothe Luce as having lived an incredible life, she reflected in her last weeks, “You know, I have had a terrible life. I married two men I really didn’t like. My only daughter was killed in a car accident. My brother committed suicide. Has my life been a life for anyone to envy?” (Brenner) Luce succumbed to brain cancer in Washington D.C. on October 9, 1987. The Washington Post eulogized her thusly, “She raised early feminist hell. To the end she said things others wouldn’t dare to – cleverly and wickedly – and seemed only to enjoy the resulting fracas…Unlike so many of her fellow Washingtonians she was neither fearful nor ashamed of what she meant to say” (U.S. House).

References

Brenner, M. (1988, March). Fast and Luce. Vanity Fair.

Retrieved from

Clare Boothe Luce – Quotes. Goodreads.

Retrieved from

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/332721.Clare_Boothe_Luce

Clare Boothe Luce. The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers.

Retrieved from

https://www2.gwu.edu/~erpapers/mep/displaydoc.cfm?docid=erpn-claluc

Luce, Clare Boothe. U.S. House of Representatives.

Retrieved from

https://history.house.gov/People/detail/17213

Luce, Clare Boothe. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/5827/clare-boothe-luce

McMillan, P. (1987, October 10). Clare Boothe Luce Dies of Cancer at 84. Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-10-10-mn-8556-story.html

Morris, S.J. (1997). Rage for fame: the ascent of Clare Boothe Luce. New York, NY: Random House.

Morris, S.J. (2014). Price of fame: the honorable Clare Boothe Luce. New York, NY: Random House.

Morris, S.J. (2014, June 19). Clare, in Love and War. Vanity Fair.

Retrieved from