I’ve noticed these days that any win gets portrayed as some great mandate for leadership in a presidential election, both for the president and his party. However, there have been no elections that I would call a major mandate since Barack Obama’s win in 2008. Democrats expanded on their House majority and turned a slight Senate majority into one that could overcome a filibuster. Obama also won the states of Indiana and North Carolina, not ones that have landed in the Democratic column since. Since that election, wins have either been narrow or in the case of Obama in 2012, still having one of the House of Congress in the control of the opposing party. The 1920 election, however, was one for the ages.

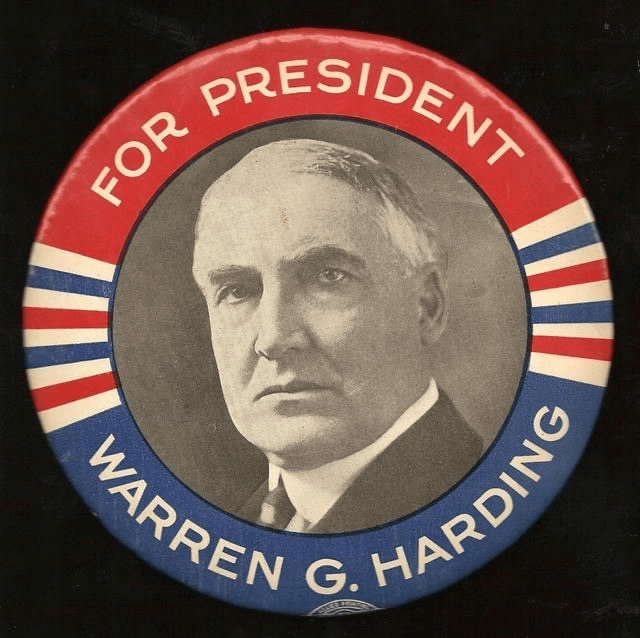

Given the unpopularity of the defeated Versailles Treaty as well as a mini-depression that was occurring, it was nigh impossible for anyone to take up Woodrow Wilson’s mantle and win. Ohio’s Governor, James M. Cox, attempted it anyway. Ohio Senator Warren Harding’s call for “normalcy” resounded across the nation as the nation stood disillusioned with progressivism, tired of extensive involvement in foreign affairs, alarmed by race riots, strikes, and an anarchist bombing of Wall Street, and hurting from the depressed economy. Although old rumors that Harding had black ancestry made their way to the public, it didn’t seem to have much of an impact, and he won in a landslide, getting 404 to Cox’s 127 electoral votes. Only the states of the former Confederacy plus Kentucky backed Cox. The Solid South also had a breakaway in Tennessee, the first former Confederate state to vote for a Republican presidential candidate since Reconstruction. Harding could fully claim a mandate, especially with the legislative results that accompanied his election.

House

The House results were catastrophic for Democrats in the North, with Republicans, already having a majority, gaining 63 seats. The following House delegations became or remained entirely Republican after the 1920 election:

Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming

Pennsylvania was with one exception entirely Republican, and that exception, Guy Campbell, would vote like a Republican in the 67th Congress and subsequently switch parties.

Outside the South and Border States, Democrats were reduced to 19 representatives:

Carl Hayden, Ariz.

Clarence Lea, Calif.

John Raker, Calif.

Edward Taylor, Colo.

John Rainey, Ill.

Adolph Sabath, Ill.

Thomas Gallagher, Ill.

Peter Tague, Mass.

James Gallivan, Mass.

Charles O’Brien, N.J.

John Kindred, N.Y.

Thomas Cullen, N.Y.

Christopher Sullivan, N.Y.

Daniel Riordan, N.Y.

W. Bourke Cockran, N.Y.

John Carew, N.Y.

Anthony Griffin, N.Y.

Peter Ten Eyck, N.Y.

James Mead, N.Y.

Guy Campbell, Penn.

The Urban Areas

Republicans had massive success in urban areas, particularly shocking being in New York City, where they won a majority of the city’s districts in Congress. This feat has not been repeated since and was achievable because Tammany Hall largely sat on their hands in this election as well as some of the left-wing vote going to Socialist Party candidates arguably cost Democrats victories in New York’s 3rd, 7th, 8th, and 23rd districts. By contrast, today the only New York City district that Republicans often win is Staten Island. New York’s 12th district once again elected Socialist Meyer London, one of only two members of the Socialist Party to ever win a seat in Congress. In neighboring New Jersey, a Republican won a seat in the Northern portion of Jersey City, a feat that has only been repeated once since.

In Illinois, Republicans won all but three of Chicago’s House seats, although Chicago was considerably more Republican than it is now. Outside of Chicago, this election produced future House Speaker Henry T. Rainey’s only reelection loss.

In Ohio, Republicans won both seats in Cleveland, a feat they have yet to achieve again.

Ethnic Germans and Irish, usually rich sources for the Democratic vote in major cities, were hostile to the Versailles Treaty and to President Wilson. These groups had beefs with Britain, and yes, at that time anti-British politics were still something that could be capitalized on in the US. The result was many ethnic Germans and Irish either voted Republican or stayed home in 1920, and the Democratic machines that served these groups were not particularly willing to help the Cox/Roosevelt ticket. The degree of success Republicans had in the 1920 election in urban areas has been unheard of since.

The Border states were a disaster for Democrats too, with them only holding the staunchly Democratic 2nd and 11th districts in Missouri, the latter based in St. Louis. In Maryland, Democrats only won Maryland’s 1st and 4th districts, the latter based in Baltimore. In Oklahoma, Republicans won five of the eight House seats. The norm was for Republicans to only hold the 8th district while the 1st district, based in Tulsa, was highly competitive. The Socialist Party in Oklahoma arguably cost Democrats the 2nd, 4th, and 6th districts. Kentucky was the only state in which things were fairly normal for Democrats, with them holding 8 of 11 of the state’s House seats.

The South remained mostly solid for Democrats, but Republicans won three seats in Tennessee that they didn’t usually win, putting Republicans on par with Democrats. The status quo of only two Republican representatives from East Tennessee would return with the 1922 election. They also won a single seat in Texas based in San Antonio, which they managed to win a few more times, as well as kept a seat in Virginia.

The Senate

The Senate Democrats took a bad lump, but the six-year terms of the Senate shielded them from worse. One retiring Democrat, Edwin Johnson of South Dakota, was succeeded by Republican Peter Norbeck, while 12 incumbents either lost reelection or renomination.

Arizona: Democrat Marcus A. Smith was defeated for reelection by Republican Ralph Cameron, making Cameron the first ever Republican elected to Congress from the young state, which at the time was usually strongly Democratic.

Arkansas – Democrat William F. Kirby lost renomination to Congressman Thaddeus Caraway, and in the South statewide the Democratic nomination contest was the real election.

California – Democrat James Phelan lost reelection to Republican Samuel Shortridge.

Colorado – Democrat Charles Thomas’s political independence resulted in him refusing to run for renomination with Democrat Tully Scot winning the primary, and then Thomas lost reelection as a member of the Nationalist Party.

Georgia – Democrat Hoke Smith lost renomination to fiery populist Thomas E. Watson.

Idaho – Democrat John F. Nugent lost reelection to Republican Frank Gooding.

Kentucky – Democrat J.C.W. Beckham lost reelection to Republican Richard P. Ernst.

Maryland – Democrat John W. Smith lost reelection to Republican Ovington Weller.

Nevada – Democrat Charles Henderson lost reelection to Republican Tasker Oddie.

North Dakota – Republican Asle Gronna lost renomination to Edwin F. Ladd, who won the election.

Oklahoma – Democrat Thomas P. Gore’s independence from the Wilson Administration cost him renomination to Congressman Scott Ferris, who lost the election to Republican Congressman John W. Harreld.

Oregon – Democrat George E. Chamberlain lost reelection to Republican Robert N. Stanfield.

The major gains of this election would result in many Republican policies being passed in the 1920s, but the extent of them would prove temporary as in 1922 Republicans would more than lose their 1920 House gains. Senate Republicans would lose seven seats. However, a Republican majority would persist in the House until the 1930 election and the Senate until the 1932 election, when the United States was in the Great Depression.