Some people of a conservative mindset may ask what happened to the Democratic Party. Interestingly, there are people whose records were considerably more moderate or even conservative before the politics of the 21st century. Some would say that a lot of Democrats back then would be Republicans now. However, this doesn’t account for politicians adapting to the directions of their parties. A prominent example of this is a recent politician in Clarence William “Bill” Nelson (1942- ).

An attorney by profession, Bill Nelson got his start in politics by working as a legislative assistant to Governor Reuben Askew with his election to the state legislature in 1972. He won reelection in 1974 and 1976, and this time put him in a good position to run for Congress. In 1978, Republican Lou Frey announced that he would not run for another term. Nelson was an ideal candidate for his time and place; a man of 36 with a model American family running against a politician who although had avoided jail-time was tied to a campaign fundraising scandal in 64-year old Republican Edward Gurney. Although this Florida district had been electing Republicans since 1962, when it first elected Gurney, Democrats had a 60-40 party registration advantage (Peterson). Furthermore, Nelson was running as a conservative Democrat thus Gurney couldn’t pin the label of liberal on him. He won the election by 24 points and established a record that was moderate to moderately conservative. Nelson opposed government funding of abortion, supported the death penalty, and backed the Reagan tax cuts in 1981. However, he supported rolling them back considerably with his support of the proposed 1983 Tax Equity bill and was supportive of funding increases for domestic programs and opposed to limiting food stamps. In 1986, Nelson was the second member of Congress and the first representative to travel into space in Space Shuttle Columbia. After all, he represented Florida’s Space Coast where Cape Canaveral is located.

In 1990, he opted against running for another term for Congress to run for governor. However, Nelson had a formidable primary opponent in former Senator Lawton Chiles Jr., and miscalculated in his campaign against him when he made Chiles’ health an issue, particularly his use of Prozac to treat depression, which was made worse by his running mate suggesting that Chiles was suicidal, a suggestion Nelson disavowed (Orlando Sentinel). Running against Chiles on mental health didn’t stick to the man that Floridians had thrice elected to the Senate, and he easily prevailed.

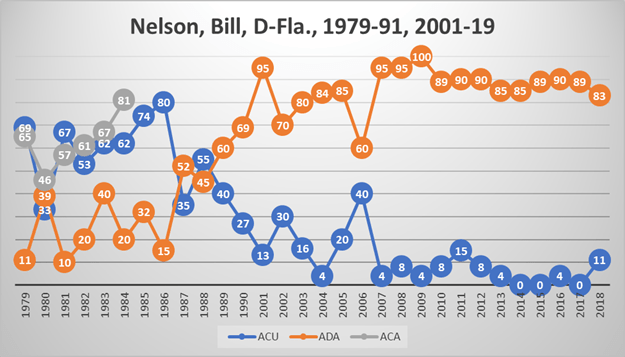

If his 1990 gubernatorial race was the end of his national career, I would be fine with the common view of him that he was a centrist or even a moderately conservative Democrat. From 1979 to 1984, he sided with the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action 63% of the time. However, Nelson’s career had quite a way to go and in 1994 the reelection of Governor Chiles also saw the election of Nelson as Treasurer, Insurance Commissioner, and Fire Marshal of Florida (yes, it is all one office). He won reelection in 1998, and his experience positioned him for a Senate run. In early 2000, Nelson resigned to run for the Senate, and just like the state’s presidential race, its Senate race was close and heated. His opponent was conservative Republican Congressman Bill McCollum, and both ran strongly negative campaigns against each other. Nelson repeatedly labeled his opponent as an extremist who would sacrifice the elderly, the poor, and the working class to coddle the rich while McCollum labeled him as “a liberal who would tax everything that moves, and some things that don’t” (Bragg). At the time, Nelson had the more solid case for the political center given his record in the House while McCollum had a pretty consistent conservative record. As political science professor Aubrey Jewitt noted, “he was known as a fairly moderate Democrat and right now that’s a good ideological place to be” (Bragg). Although Bush very narrowly officially won the state by 537 votes in one of the nation’s most controversial elections, Nelson edged out McCollum in the Senate election by 5 points.

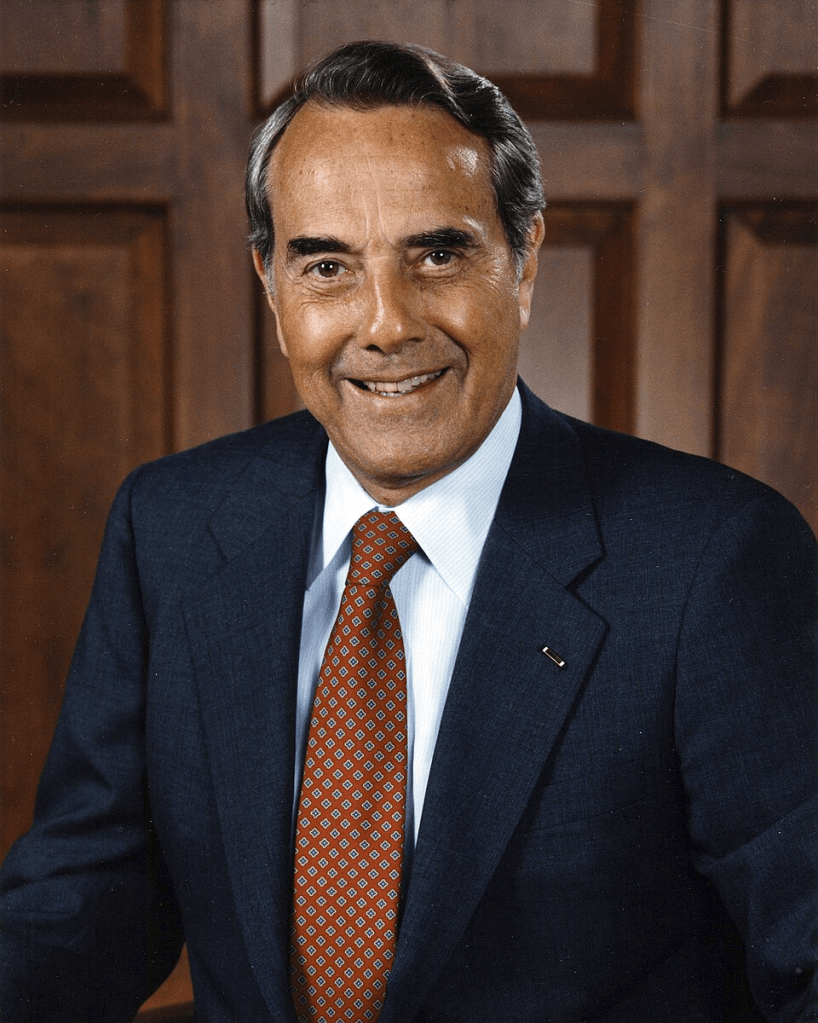

Senator Nelson

It should be noted that representing a district and representing a state can be a different ballgame and some politicians indeed have shifted left from when they represented a district as opposed to a state. Prominent examples include Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York who as a representative of an upstate district was pro-gun rights and now is pro-gun control and even more dramatically Charles Goodell of New York who went from moderately conservative establishment Republican to staunchly liberal anti-Vietnam War Republican in the Senate in what seems to have been an unsuccessful effort to make a Republican-Liberal Party coalition run for a full term in 1970. Indeed, the contrasts between Nelson as a representative and Nelson as a senator are considerable. Although in his first term in the Senate, you could make an argument that he seemed to represent was he was selling to Floridians, and contrary to what McCollum claimed he did vote for some tax reductions, notably ending the estate tax and extending the Bush tax cuts (although he had originally opposed them). However, in his first term he nonetheless sided with the American Conservative Union (ACU) 20% of the time and liberal Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) 79% of the time. As a representative, he had agreed with the ACU 55% of the time and ADA only 34% of the time. The 2006 election gave him a green light to be a party loyalist even more as he was reelected by 22 points not only due to a poor political climate for Republicans but also due also a weak candidate in Congresswoman Katherine Harris.

In his second term, Nelson was strongly with the liberal position and a loyalist to the agenda of the Obama Administration. He even stated his support for a “public option” for healthcare in 2009, an issue of contention among Senate Democrats (Dunkelberger). Indeed, Nelson sided with ACU 8% of the time in this term. Now wait…you might say, that’s just a conservative skew! However, he also sided with ADA positions 93% of the time! Thus, again, both conservatives and liberals agreed on where he stood on the American political spectrum. One area in which he was consistent over time on the conservative position was on favorability to free trade agreements. Furthermore, with Obama winning reelection not only nationally but also in Florida in 2012, Nelson pulled off an 11-point win. Once again, Republicans had run a weak candidate, this time in Congressman Connie Mack IV. A Florida Republican operative had said about Mack, “He’s a weak candidate. Let’s just be honest. He is a pale shadow of his father’s greatness as a politician” (Miller). Nelson’s third term represented more agreement with the Obama Administration as after all, Florida voters had opted to return him to office!

His siding with ACU and ADA differed a bit in his third term: 3% for the former and 87% for the latter. I should note that it is my opinion based on what I’ve seen of their ratings that ACU under Matt Schlapp has made their grading of politicians tougher and more oriented towards the politics of Rand Paul. However, Nelson’s loyalty to the Obama Administration was noted by journalist Ledyard King (2014) when he wrote that a new analysis showed that along with 16 other Senate Democrats he “voted in line with President Barack Obama’s positions 100 percent of the time last year”. In 2018, although Nelson in theory had the benefit of a good political environment given that this was looking to be a backlash election against Trump, he undoubtedly lacked the benefit of a weak candidate. Rick Scott was reasonably popular as Florida’s two-term governor, and better yet for the Republicans they were making inroads with Hispanic voters overall and not just increasing their support among Cuban-Americans (Ogles). Furthermore, Florida was increasingly moving to Republicans and Nelson’s loyalist record to President Obama as well as his opposition to nearly all Trump policies wasn’t playing so well in Florida now. This was highlighted with his announcement before Trump picked a Supreme Court nominee in 2018 that he expected to vote against the nominee based on protecting Roe v. Wade (Smith). The issue of abortion was yet another way in which Nelson had flipped; as a representative he had had an almost entirely anti-abortion record while as a senator, he had a record almost entirely supportive of abortion rights, only voting to prohibit taking minors across State lines without parental consent for abortions in 2006. This election was so close that it was decided by just over 10,000 votes, or 0.13% of the vote, with Scott prevailing. Nelson subsequently served as the administrator of NASA from 2021 to 2025.

In his overall Senate career, Nelson sided with ACU 10% of the time and ADA 86% of the time. Both ADA and ACU found Senator Nelson’s peak year of dissent from the liberal position as 2006, when he only sided with the liberal position on 60% of the votes they considered to be most important. Over his entire career, he sided with ACU 27% of the time and ADA 65% of the time, with his DW-Nominate score standing at -0.193. While his overall record does paint him as a moderately liberal Democrat, it makes more sense to see Representative Nelson as distinct from Senator Nelson, much like it made sense to see Representative Goodell of New York as distinct from Senator Goodell of New York.

The change of Bill Nelson overtime:

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Bragg, R. (2000, October 18). The 2000 Campaign: A Florida Race. The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Chiles Says Slip in Pep Got Him Back on Prozac. (1990, August 8). Orlando Sentinel.

Retrieved from

Dunkelberger, L. (2009, October 11). Nelson says he supports public option for health care. The Gainesville Sun.

Retrieved from

King, L. (2014, February 9). View from the Beltway: Nelson’s votes are parallel to Obama stance. Florida Today.

Retrieved from

Miller, J. (2012, June 20). Rep. Connie Mack IV Still Has Uphill Battle for Senate Seat. Roll Call.

Retrieved from

https://rollcall.com/2012/06/20/rep-connie-mack-iv-still-has-uphill-battle-for-senate-seat/

Nelson, Clarence William (Bill). Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/14651/clarence-william-bill-nelson

Ogles, J. (2019, January 13). Rick Scott pollsters show strong Hispanic support helped victory. Florida Politics.

Retrieved from

Peterson, B. (1978, September 10). Florida’s Ex-Sen. Gurney Striving to Return to Congress. The Washington Post.

Retrieved from

Sen. Bill Nelson. American Conservative Union.

Retrieved from

http://ratings.conservative.org/people/N000032?year

Smith, A.C. (2018, July 2). Bill Nelson says he expects to vote against President Trump’s Supreme Court nominee. Miami Herald.

Retrieved from

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/state-politics/article214206684.html