At one time, California Republicans were of great significance; Hiram Johnson was a celebrated leader of the progressive faction of the Republican Party and nationally known for his role in defeating the Versailles Treaty, Richard Nixon was from California, and Ronald Reagan’s political career began in California. As late as 2023, a California Republican had a leadership role, Speaker Kevin McCarthy. Another figure of significance, although not as well known as Nixon or Reagan, was William Fife Knowland (1908-1974), who was one of the foremost figures of Washington at the height of his power.

Knowland’s birth as well as how his father, J.R. Knowland, regarded him set him up for a career in politics. The elder Knowland had been a member of Congress in the conservative faction of the party from the Roosevelt to Wilson Administrations representing Oakland (different time, different Oakland). J.R. also was a mentor to Earl Warren, who would diverge considerably from conservative politics with time. From his youth, the younger Knowland was an active player in California politics, serving in the State Assembly from 1933 to 1935 and the State Senate from 1935 to 1939. In 1942, at the age of 34, he joined the army; he and his father’s newspaper, the Oakland Tribune, for which he worked as assistant publisher, had supported the peacetime draft law and he figured that if he supported such a policy that he should live it for the duration of the war.

After Senator Hiram Johnson died in 1945, Warren approached J.R. Knowland about a temporary Senate appointment, but he declined and recommended his son. Interestingly, Knowland learned of his appointment by the reading the Stars and Stripes newspaper; his wife Helen had attempted to call him to tell him about his appointment, but her call was turned down by military censors as “not essential government business” (Hill). The army honorably discharged him and sent him to Washington to serve.

Although Knowland would develop a public reputation as a conservative, in his first years in the Senate he was politically moderate. Indeed, when appointed, he publicly identified himself as a “liberal Republican pointed toward national social programs and business stability and international cooperation based on a non-partisan approach to foreign policy” (Montgomery and Johnson, 53). He demonstrated his willingness by backing President Truman’s Full Employment bill in 1945, which would be signed into law but in a compromised form the following year. He was, however, fiscally conservative, and was concerned about the accumulation of debt (Montgomery and Johnson, 67). Knowland’s warnings on debt have since been largely unheeded by both parties. In 1950, Knowland, a strong supporter of authority of states, sponsored an amendment to that year’s Social Security bill restricting the authority of the Social Security Administrator to require states to adopt federal standards for unemployment compensation, requiring a 90 day notice for noncompliance findings and required judicial review before funds could be withheld from states. The amendment was adopted as part of that year’s legislation. Bill Knowland was also not what we would think of as a politician temperamentally, he was humorless, not charismatic, and had a tendency not to remember people he had previously met. However, he was also highly principled, and indeed the integrity of his public life is unblemished. However, Knowland’s private life was a different story. Although he and his wife Helen loved each other, both had extra-marital affairs. They had married very young and hadn’t had a chance to “sow their wild oats”. Helen conducted an affair with journalist and later senator Blair Moody, while Knowland had an affair with Moody’s wife, Ruth.

In 1952, Knowland faithfully backed fellow Californian and family friend Earl Warren for the Republican nomination for president. Richard Nixon was also supposed to be a backer of Warren, but he double-crossed Warren by working behind the scenes to get the California delegation to flip to Eisenhower on key procedural votes during the Republican National Convention, thus securing his nomination (Farrell). Knowland himself had received an offer for an arrangement from Taft which he declined, most likely meaning a vice president nomination in exchange getting California’s delegates to his side. Had Knowland acted before Nixon, he would have secured the nomination for Taft. And since Taft died on July 31, 1953, we would have had President Knowland. This demonstrates that principles in politics can come at a cost. Earl Warren, however, would get a pretty substantial consolation prize with the advocacy of Knowland: Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. During the Eisenhower presidency, he increasingly identified with the conservative wing, particularly once he succeeded Taft as Senate Republican leader, and voted against Senator Joseph McCarthy’s censure in 1954. Although not a slavish devotee of his, indeed Knowland had voted against his pushes to reject Charles Bohlen’s nomination as Ambassador to Russia as well as reducing aid to nations trading with Red China in 1953 and objected to his breaches of Senatorial decorum, he nonetheless thought that McCarthy’s prime sin was exaggeration as opposed to the validity of his crusade. He reflected on McCarthy in 1970, “…one of Joe McCarthy’s liabilities was a tendency to overstate his case. I think he hurt himself a good deal by this overstating his case, and he offended a lot of Republican senators by some of the statements he made” and further stated, “I haven’t agreed with Senator Fulbright on the way he performed either during the Eisenhower Administration or during the Johnson Administration, or even currently. But he was a senator of the United States, and I really resented when McCarthy got up on the floor and referred to him as Senator Halfbright. I mean, it was this kind of a thing, you know, that just isn’t done” (Frantz, 21).

As a leader, Knowland was not as skilled as Democratic leader Lyndon B. Johnson, who often got the better of him. As veteran journalist William S. White noted, “Knowland was very inflexible and not one-tenth as bright as Johnson in maneuvers and so on. So Johnson took care that he always maintained a very close personal relationship with Knowland, so that he could approach him at any time. He really just sort of overwhelmed Knowland with his brilliance as a leader” but also added that, “It only meant that he was a more intuitive man, operating with more freedom of motion in a more relaxed party. To put it another way, the stiffness of Knowland, an honorable and very down-right man quite incapable of subtlety, had a kind of inevitability in the very nature of his party. The flexible, inventive, more volatile characteristics of Johnson were in a sense really the human characteristics of his party” (Montgomery and Johnson, 140-141). President Eisenhower also noted Knowland’s deficit in leadership. He wrote in his diary on January 18, 1954, “Knowland means to be helpful and loyal, but he is cumbersome. He does not have the sharp mind and the great experience that Taft did. Consequently, he does not command the respect in the Senate that Senator Taft enjoyed” (Montgomery and Johnson, 150-151). While Knowland was without question a man of integrity in his public actions, his leadership deficiencies precluded moving higher. Interestingly, something that also connects to today is Knowland’s recounting of himself and other members of the Republican Senate leadership trying to convince President Eisenhower to replace some of Truman’s people in government departments, which he would not budge on as he did not want to be seen as attacking the civil service (Frantz, 24-25). Republican presidents since have been more friendly to the views of Knowland and other Republican bigwigs in the need to build up the party. Although Eisenhower had his differences with Knowland and others in the Republican leadership, Knowland rejected the interpretation that Eisenhower was ideologically closer to Democratic leader Lyndon B. Johnson than the GOP (Frantz, 29). In 1957, he sponsored an unsuccessful amendment retaining the restriction on bartering of commodities for communist nations, in keeping with his anti-communist stance. In 1958, Knowland successfully introduced an amendment blocking liberalization of the Battle Act as an amendment to foreign aid legislation to permit aid to communist nations aside from the USSR, China, and North Korea. Consistent with his views on unions, he also sponsored two unsuccessful secret ballot amendments to that year’s proposed labor reform bill.

Knowland and Civil Rights

After the decision of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), legislative action was bound to follow. In 1956, the House passed an Eisenhower Administration-backed civil rights bill, which focused on voting rights. Knowland and Majority Leader Johnson wanted to hold off on civil rights until after the election, and all but five senators agreed. In 1957, Knowland backed the Eisenhower Administration bill fully, and managed to bypass the Senate Judiciary Committee to bring it to the floor. The committee was chaired by James Eastland (D-Miss.), one of the most prominent and outspoken segregationists who made the committee a graveyard for civil rights bills. However, Knowland did not prevail in his effort to prevent weakening amendments, most notably striking the section of the bill granting the Attorney General authority to initiate 14th Amendment lawsuits and the adoption of a jury trial provision for contempt of court voting rights cases. Majority Leader Johnson had prevailed in the adoption of the latter two, which resulted in passage of the bill, as the Southern bloc had agreed not to have a coordinated filibuster if these weakening amendments were added. Johnson got a good deal of credit for securing the passage of the first civil rights bill, which also cemented him as a national rather than regional figure and made him a presidential contender.

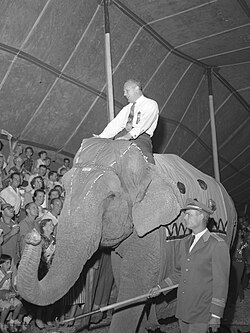

Knowland atop an elephant during the 1958 Senate campaign.

Defeat and After

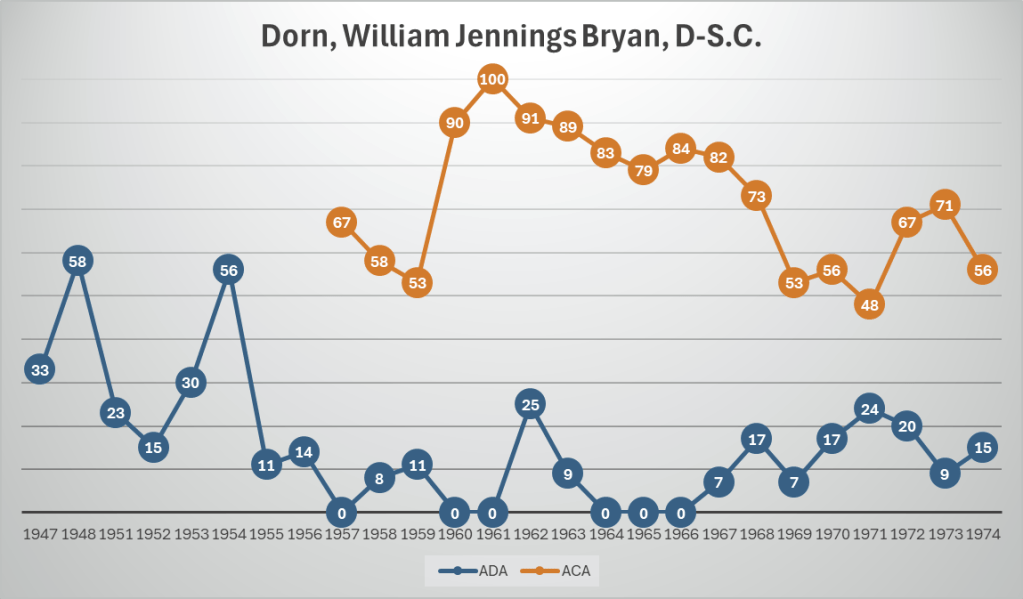

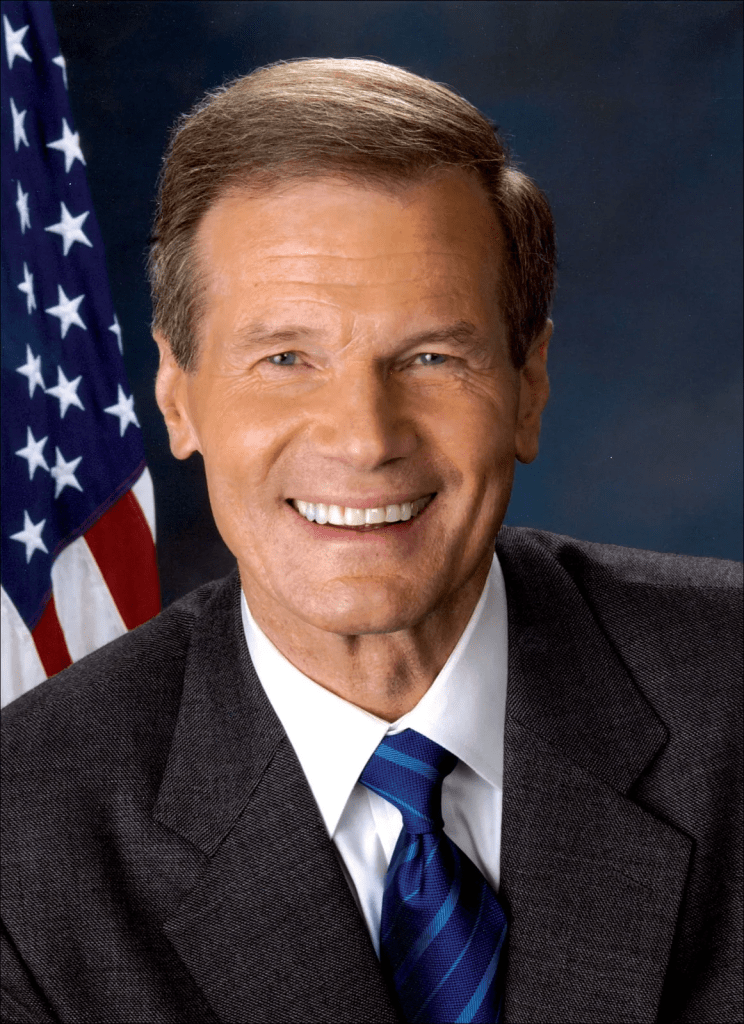

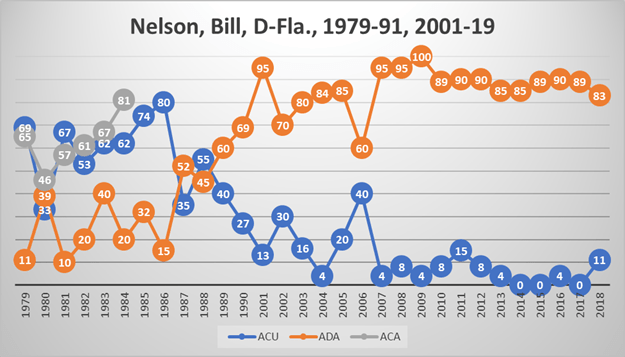

I have already covered the story of Knowland and the 1958 election, so long story short, he lost the gubernatorial election badly to Pat Brown in a deeply troubled campaign, and this ended his political career. Knowland sided with the liberal Americans for Democratic Action 31% of the time, and the conservative Americans for Constitutional Action 77% of the time, both measures indicating a moderate conservatism. His DW-Nominate score is a 0.227. Knowland’s political career was over at the age of 50, and he resumed publishing, succeeding his father as publisher for the Oakland Tribune.

Although Helen Knowland’s extra-marital activities had ended with Blair Moody’s death in 1954, Bill’s affair with Ruth lasted until her death in 1961, and he continued to have affairs after. Finally, in 1972, the couple divorced so Bill could marry a much younger woman. However, she was a tempestuous woman, a full-blown alcoholic, and addicted to spending. This, combined with Knowland’s gambling addiction drained the family fortune. By 1974, Knowland was over $900,000 (over $5 million in today’s money) in debt to banks and mobsters. He considered selling the Oakland Tribune, but he ended up landing on a different course of action. On the morning of February 23, 1974, Knowland drove up to his compound in Guerneville, got his gun, went to his pier on the Russian River, and fired a shot into his right temple, dying instantly at the age of 65.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Farrell, J.A. (2017, March 21). Richard Nixon’s Ugly, 30-Year Feud with Earl Warren. Smithsonian Magazine.

Retrieved from

Frantz, J.B. (1970, March 23). Oral history transcript, William F. Knowland, interview 1 (I). LBJ Presidential Library.

Retrieved from

https://discoverlbj.org/item/oh-knowlandw-19700323-1-00-05

Knowland, William Fife. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/5343/william-fife-knowland

Montgomery, G.B. & Johnson, J.W. (1998). One step from the White House: the rise and fall of Senator William F. Knowland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Retrieved from

https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft4k4005jq;chunk.id=0;doc.view=print