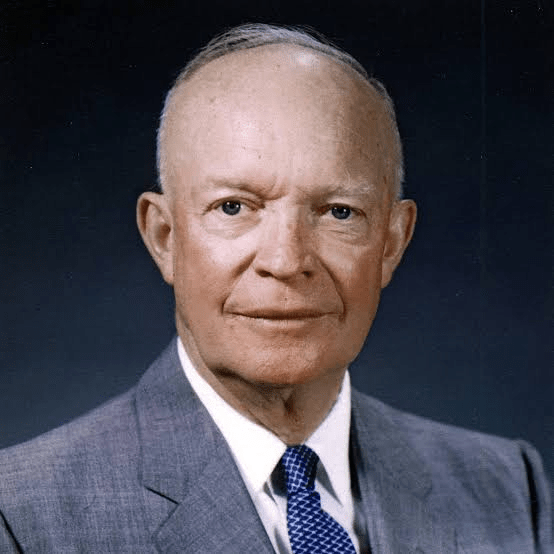

In 1946, the American public elected a Republican Congress for the first time since the Great Depression. One of the fresh faces in Washington who vanquished a Democrat was another Democrat in Otto Ernest Passman (1900-1988) of Monroe, Louisiana. Passman, an appliance manufacturer and salesman by profession, had succeeded in ousting conservative Democrat Charles McKenzie in the 1946 nomination contest. However, if national Democrats got their hopes up that he would be more loyal to party line than his predecessor, they were in for a great disappointment. Passman was one of the most agreeable in the House to the conservative agenda of the 80th Congress; in his first year, Americans for Democratic Action scored him a 25%, one of the lowest among House Democrats that year.

Passman the “Lord High Executioner of Foreign Aid Bills”

Passman was a frequent thorn in the side of the internationalist leadership in both parties. As chairman of the appropriations subcommittee on foreign aid, he was frequently pushing for budget cuts, with his critics calling him the “Cajun Cassius” and being responsible for reduction of annual presidential foreign aid requests by an average of 20% from 1955 to 1965, resulting in Time Magazine (1965) calling him the “lord high executioner of foreign aid bills”. He had also been one of the few Democrats to vote against the Marshall Plan in 1948. Passman so ticked off President Eisenhower that he once told an aide something similar to what President Truman told an aide regarding J. Robert Oppenheimer, “Remind me never to invite that fellow down here again!” (Time Magazine) President Kennedy wasn’t terribly happy with him either. He once told an aide in exasperation, “What am I going to do about him?” (Time Magazine) Appropriations Committee Chairman Clarence Cannon (D-Mo.) would not rein him in, as although he wasn’t an opponent of foreign aid himself, he also would sometimes push for budget cuts regardless of whether the president wanted it or not, regardless of party. Passman said regarding presidential support, “What the President wants does not mean a damn thing to me unless it makes sense” (Time Magazine, 1957). Both Cannon and Passman could be peppery in the carrying out of their duties, further aggravating presidential and Democratic Party leadership. The essence of Passman’s critique of foreign aid was that it propped up despots whose regimes might have otherwise collapsed (Curtis). There has since been research that suggests that Passman was right. For instance, a 2016 paper by Faisal Z. Ahmed (2016) found that “U.S. aid harms political rights, fosters other forms of state repression, and strengthens authoritarian governance”. Passman did, however, do a solid for the Johnson Administration when he successfully pushed a compromise to allow shipments of wheat to the USSR and Hungary in 1963 against fierce Republican opposition.

Passman the Powerless

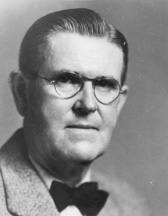

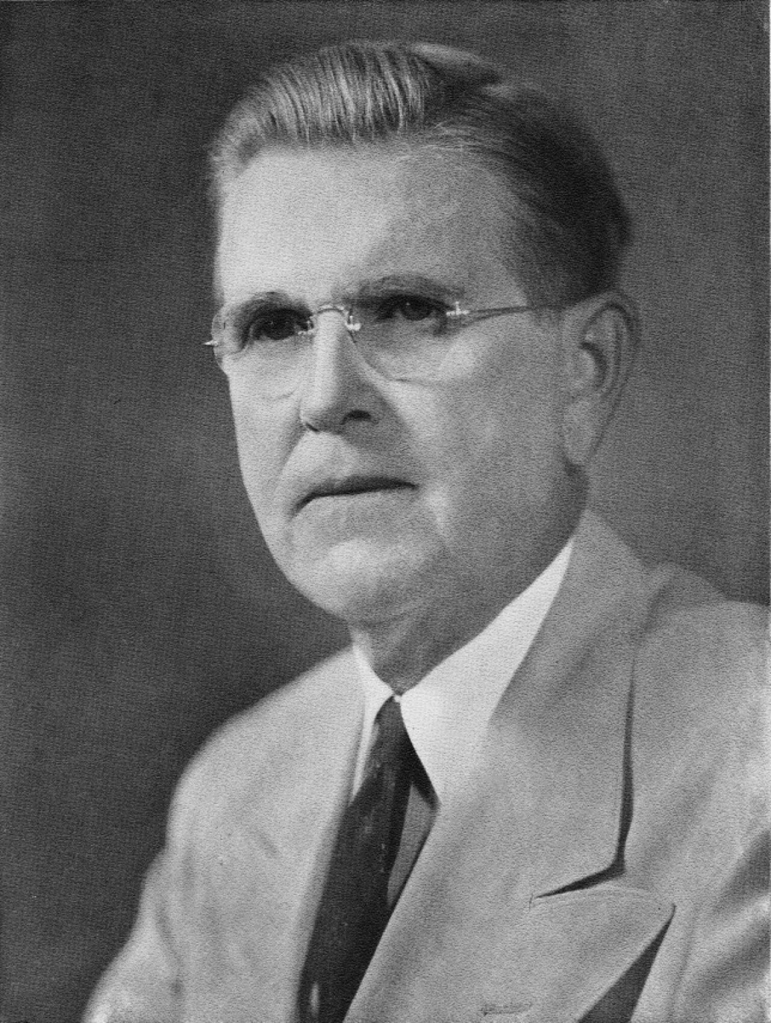

Passman’s power was conditioned on Cannon permitting him free reign, and Cannon’s death in 1964 resulted in a far less favorable successor in George Mahon of Texas. Although Mahon was not a liberal, he was willing to cooperate with his fellow Texan Lyndon B. Johnson, and this included the subject of foreign aid. Although he allowed Passman to stay on as chairman, he reduced the membership of his subcommittee from 11 to 9, making most of its membership favorable to foreign aid and resulting in Passman losing committee votes, and Mahon even deprived him of the ability to write reports on pending legislation as they contradicted what the majority wanted (Time Magazine, 1965).

Foe of 1960s Domestic Liberalism

Among the Louisiana delegation, Passman was strongly opposed to most of the liberal domestic programs of the 1960s. He voted against aid to medical schools and students and accelerated public works in 1963, against urban mass transit legislation, food stamps, and the Economic Opportunity Act in 1964, and federal aid to education and Medicare in 1965. Passman did have something of a soft spot for minimum wage legislation, and backed increases in 1961 and 1966. His record on civil rights is what you’d expect from a Louisiana representative of his time and place. Given Passman’s dissatisfaction with liberalism in the 1960s, he was certainly looking for an alternative, and one came with Richard Nixon in 1968.

Embracing Nixon

Although a Democrat, we have already established that Otto Passman was not the sort of Democrat we think of today, and he was quite pleased with President Nixon. As he had with President Johnson, he supported President Nixon’s Vietnam War policies. On social issues, Passman was largely on the conservative end, but he made a rather striking exception in his opposition to a school prayer amendment to the Constitution in 1971. His support for Nixon even extended beyond his resignation, with him being one of only three representatives to vote against adopting the report on his impeachment proceedings. Passman stated in support of Nixon after his resignation, “I contend that Richard M. Nixon is the greatest President this country ever had. Rather than take any chance of doing anything offensive to this great man, I decided to vote ‘no’” (Rosenbaum). Can you imagine a Democrat today saying this about President Trump? Passman’s overall ideology differs somewhat between sources. He was in accord with the position of Americans for Constitutional Action 70% of the time from 1957 to 1976, only 17% with the liberal Americans for Democratic Action from 1947 to 1976, and his DW-Nominate score was a -0.056, which is conservative for a Democrat.

Koreagate

In 1976, a scandal broke regarding South Korean millionaire lobbyist Tongsun Park. Park had been spreading money around Washington both to promote his rice business and to maintain US military presence in South Korea as a bulwark against North Korean aggression, and Passman was one of 31 representatives named by Park as having accepted money from him. His involvement in this scandal resulted in his narrow loss for renomination in 1976 to Jerry Huckaby. On April 1, 1978, Passman was indicted for accepting $98,000 in illegal gratuities or bribes from 1972 to 1975, and allegedly in exchange he lobbied Congress to maintain Park’s monopoly as an agent for selling American rice to South Korea (Columbia Missourian). However, Passman managed to get the venue of his trial changed to his home city of Monroe, given that there was also a tax evasion charge. His attorney portrayed him as “an unknowing victim of an evil Korean conspiracy” and he was acquitted (The New York Times). This acquittal, however, many have been produced by the move in venue as well as sympathy he got from his poor health.

Sex Discrimination

Although Passman had been one of many members of Congress to vote for the Equal Rights Amendment, he has the dubious distinction of being the first member of Congress to be sued for sex discrimination. In 1974, he fired his assistant, Shirley Davis, and wrote in her termination letter that it was essential that a man be in her role. She sued him, and the case established a Supreme Court precedent in 1979’s Davis v. Passman, which affirmed that members of Congress can be sued for discrimination. The case was settled for an undisclosed amount that year.

The Last Years

Passman ended up living longer than would be expected given his poor health in the late 1970s. His wife died in 1984, and he soon remarried to his secretary, who was over 25 years younger than him. Passman died on August 13, 1988, at the age of 88.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Ahmed, F.Z. (2016). Does Foreign Aid Harm Political Rights? Evidence from U.S. Aid. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 11: 1-35.

Retrieved from

Curtis, J. (2021, March 17). Author details Otto Passman’s life in latest book. The Ouachita Citizen.

Retrieved from

Passman Is Acquitted On Charges of Taking Payments by Korean. (1979, April 2). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Passman, Otto Ernest. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/7228/otto-ernest-passman

Rosenbaum, D.E. (1974, August 21). House Formally Concludes Inquiry Into Impeachment. The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Second congressman indicted. (1978, April 1). Columbia Missourian.

Retrieved from

The Congress: A Tartar Tamed. (1965, September 17). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,842094-1,00.html

The Nation: The Gutting of Foreign Aid. (1957, August 26). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6800125/the-nation-the-gutting-of-foreign-aid/