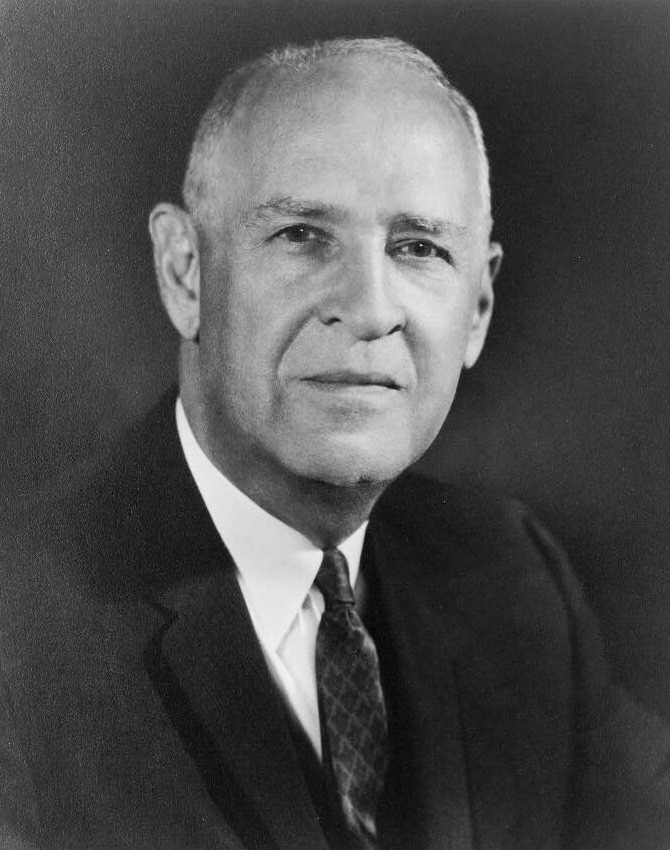

Richard Russell, the leader of the Southern Democratic faction of the Senate.

Southern Democrats occupy something of a debated space in their politics in the liberal/conservative range of things. Conservative Republicans don’t like the idea of them being connected to them and will argue that most didn’t switch to the GOP. There are some reasons for that that stand outside of ideology, such as figuring that they would do better sticking to their regional brand of Democratic politics, as many in the South still were in the habits of their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers in voting Democratic. This being said, the Southern Democrats as a group although were not the staunchest conservative group in the Senate (that would be the conservative wing of the Republican Party of the day), many were conservative enough to have an informal “Conservative Coalition” with Republicans to oppose many liberal policies. There were issue areas in which this coalition weakened…on the Southern Democratic side it was on agriculture and public power, and on the Republican side it was on civil rights and particularly during the Eisenhower Administration on foreign aid, to which Southern Democrats had become increasingly antagonistic.

Based on lifetime modified ACA scores (thus based on records from 1955-1984), this is how the Senate Southerners, who served during the Civil Rights Era (1954-1968) did on conservatism. I will be ranking them from least to most conservative:

Estes Kefauver (D-Tenn.) – 5%

Lowest score: 0% (1955, 1956, 1962, 1963)

Highest score: 11% (1957)

Kefauver in short: Kefauver, who I have written about before, was a liberal populist who was more amenable to civil rights than many Southern senators, indeed Tennessee had become a bit of a softer state on the subject, while it used to be that it was only Republicans in East Tennessee who would vote for civil rights. Kefauver’s biggest moments in the sun were his publicized investigations of the mafia and his vice-presidential run in 1956. He would play no role in the civil rights debates of the 1960s as he died before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was debated.

Ross Bass, (D-Tenn.) – 7%

Lowest score(s): 0% (1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1966)

Highest score: 33% (1957)

Bass in short: Bass’s record here includes his time in the House and his time in the Senate during the Great Society Congress. He was in terms of his ideology a true successor of Estes Kefauver. However, Bass lost the 1966 Democratic primary to Frank Clement, who proceeded to lose to Republican Howard Baker Jr.

Ralph Yarborough (D-Tex.) – 8%

Lowest score: 0% (1962, 1967, 1970)

Highest score: 17% (1968)

Yarborough in short: Ralph Yarborough was Texas’ best-known champion of liberalism, backing strongly Democratic national programs. He even voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the only senator from a former Confederate state to do so, and that year defeated his Republican challenger by the name of George H.W. Bush. The times in which Yarborough voted conservative per ACA included some foreign aid votes, and he did vote with LBJ on civil rights in 1957 and 1960. Yarborough’s liberalism became tiresome for Texans, and he lost renomination to moderate Lloyd Bentsen in 1970.

W. Kerr Scott (D-N.C.) – 10%

Lowest score: 0% (1958)

Highest score: 20% (1955)

Scott in short: W. Kerr Scott was a progressive Democrat on most matters save for the civil rights issue, certainly a New Dealer in spirit and deed. He died in office in 1958, resulting in his replacement with a much more conservative man who also went by his middle name: B. Everett Jordan.

Lyndon B. Johnson (D-Tex.) – 10%

Lowest score: 0% (1955)

Highest score: 22% (1957)

Johnson in short: As Senate Majority leader, Lyndon B. Johnson was a national figure, and was an especially talented leader, pulling off narrow victories, and he with great frequency backed liberal positions despite liberals mistrusting him and considering him something of a conservative. His presidency would put this mistrust (at least on domestic issues) to rest for liberals.

Walter George (D-Ga.) – 18%

Lowest score: 8% (1956)

Highest score: 40% (1955)

George in short: This period catches the very last years in Walter George’s long career, as he had served in the Senate since 1922. his low score here reflects a bit of a softening in his final years more towards where he stood at the beginning of his career. In the middle of his career, George had gained praise as a principled dissenter of much of what FDR stood for.

Albert Gore Sr. (D-Tenn.) – 21%

Lowest score: 0% (1962)

Highest score: 75% (1955)

Gore in short: The father of the much more known Al Gore, Gore Sr. was known as one of the most liberal of the Southerners in the Senate. This didn’t only manifest itself in support for much of the national Democratic agenda but also on his votes on some social issues, and one that was particularly politically damaging was his vote against Everett Dirksen’s school prayer amendment in 1966. Gore’s positions on the Vietnam War also didn’t do him favors in Tennessee, and he lost reelection to Republican William Brock in 1970.

Herbert S. Walters (D-Tenn.) – 24%

Lowest score: 7% (1963)

Highest score: 40% (1964)

Walters in short: Walters was an interim replacement after the death of Estes Kefauver. There really isn’t that much to say about him. However, ACA and ADA do strongly disagree on Walters’ ideology, so that’s of note.

J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.) – 25%

Lowest score: 4% (1963)

Highest score: 54% (1968)

Fulbright in short: The name Fulbright lives on the Fulbright Scholarship, and he was one of the strongest internationalists in the South. Undoubtedly one of the more liberal Southern Democrats, he could nonetheless, based on the ACA vote selection, stood for the conservative position 25% of the time. He both sponsored the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and then turned against the Vietnam War as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Fulbright’s record on race (although he could at least vote to confirm Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court), his Faustian bargain for power if you will, ended up contributing to his renomination loss in 1974.

Olin Johnston (D-S.C.) – 30%

Lowest score: 19% (1963)

Highest score: 50% (1960)

Johnston in short: Olin Johnston had during the 1930s been a strong supporter of FDR, being the state’s New Deal governor. His bid against Senator “Cotton Ed” Smith fell short in 1938, but the second time was a charm as he won a rematch in 1944. Senator Johnston’s record consisted of a lot of domestic liberalism (he supported the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 and Medicare) but he frequently voted against foreign aid. Indeed, Johnston had been one of the few Southern Democrats to vote against the Marshall Plan in 1948.

J. Lister Hill (D-Ala.) – 31%

Lowest score: 7% (1959)

Highest score: 54% (1967)

Hill in short: Lister Hill, who I wrote about quite recently, had had a longstanding reputation as a New Dealer and a Fair Dealer who specialized in public health. However, his state was moving quite to his right, and it was to the extent that he thought it best to retire in 1968.

John J. Sparkman, D-Ala. – 35%

Lowest score(s): 0% (1956, 1959)

Highest score(s): 75% (1970, 1972)

Sparkman in short: John Sparkman was much of the same New Deal class as Lister Hill, and was the last segregationist to be on a Democratic Party presidential ticket, being the candidate for vice president in 1952. Sparkman certainly moved to the right after 1962, although far from staunch conservative. By 1978, he had clearly stayed in office too long and bowed out of reelection.

George Smathers, D-Fla. – 38%

Lowest score: 18% (1962)

Highest score: 73% (1968)

Smathers in short: George Smathers was certainly a turn right from his predecessor, Claude Pepper. However, among the Southern Democrats of his time, he was certainly one of the more liberal. Although Smathers signed the Southern Manifesto, he proved more flexible than many others, voting for the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the Constitutional amendment banning the poll tax. He even privately hoped the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would pass even though voting for it was politically impossible for him. Smathers was also a close friend of JFK and was one of two options to replace Lyndon Johnson had Kennedy lived to the 1964 election. Smathers chose not to run for reelection in 1968.

Russell Long (D-La.) – 42%

Lowest score: 10% (1966)

Highest score: 73% (1970)

Long in short: Long’s record seems to zig-zag a bit, with him strongly supporting President Johnson’s Great Society during the Great Society Congress, but he moves to the right towards the Nixon presidency. On civil rights, he seemed to have a fairly easy time adjusting to the changing South, and his name and influence far from hurt him. He also was one of the Democratic senators to support President Reagan’s tax reductions. Long would opt not to run for reelection in 1986.

Thomas Wofford (D-S.C.) – 44%

Wofford in short: Perhaps the least notable senator in this entire list, as he served in the interim after Strom Thurmond briefly resigned from the Senate, only to win again.

Fritz Hollings (D-S.C.) – 46%

Lowest score: 28% (1976)

Highest score: 71% (1967)

Hollings in short: Hollings was the last of these senators to leave office, retiring in 2004. Although Hollings started out as a bit of a conservative, he found his place as a moderate and stuck to that for a long time. He was also known for his outspoken and occasionally offensive remarks. Hollings was also known as the “Senator from Disney” for his advocacy for the company.

William B. Spong Jr. (D-Va.) – 49%

Lowest score: 38% (1971)

Highest score: 63% (1969)

Spong in short: Spong was a straight-up moderate, and he had been recruited by President Johnson in 1966 to run in the Democratic primary against A. Willis Robertson. Robertson had two things going against him: the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which had expanded the electorate, and his age. Spong defeated him, but only served a term until he was defeated in 1972 by Republican Congressman William Scott. Spong contributed a rather funny name when senators were trying to come up with ridiculous names for bills, that being the hypothetical legislation sponsored with Senators Hiram Fong (R-Haw.) and Russell Long (D-La.) protecting the copyrights of songwriters from Hong Kong, which would be titled the “Long-Fong-Spong-Hong-Kong-Song Bill”.

Price Daniel (D-Tex.) – 53%

Lowest score: 50% (1956)

Highest score: 60% (1955)

Daniel in short: Daniel made much more of an impact as governor after his Senate term. He seemed to be about where many Texans were politically at the time of his service in the Senate.

Allen Ellender (D-La.) – 57%

Lowest score: 31% (1956)

Highest score: 83% (1964)

Ellender in short: I wrote a lot about Allen Ellender recently, which you can read. He was kind of a hodgepodge of views liberal and conservative, although his later career trended more conservative than liberal. Also notably supported FDR’s court-packing plan in 1937. Ellender died in office in 1972.

B. Everett Jordan (D-N.C.) – 61%

Lowest score: 38% (1963)

Highest score: 80% (1969)

Jordan in short: Succeeding the late W. Kerr Scott, Jordan was miles more conservative than him, voting frequently with Sam Ervin. However, Jordan did show some independence from what was expected of Southern Democrats, such as his opposition to the Vietnam War later in his career. He lost renomination to Congressman Nick Galifianakis, who would proceed to lose the election to Republican Jesse Helms.

Herman Talmadge (D-Ga.) – 62%

Lowest score: 22% (1979)

Highest score: 83% (1970)

Talmadge in short: Herman Talmadge was elected to succeed Walter George in 1956, and was known as a hardliner on segregation. Although his reputation was quite right-wing, he was more variable than his reputation let on, such as voting for the Economic Opportunity Act in 1964 and Medicare in 1965. His finest hour in Washington was when he served on the Watergate Committee, which raised the profiles of most who served on it. However, his censure for ethics violations damaged his prospects and although efforts were made to rally black support for Talmadge in 1980, selling him was difficult and many blacks had negative connotations with the Talmadge name. He lost reelection to Republican Mack Mattingly.

Spessard Holland (D-Fla.) – 66%

Lowest score: 40% (1958)

Highest score: 94% (1961)

Holland in short: Holland was uniformly opposed to civil rights with the sole exception of his Constitutional amendment to ban the poll tax in 1962. He was one of the more oppositional senators to domestic liberalism, including voting against the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 and against Medicare, unlike his fellow Floridian Smathers. Holland retired in 1970.

Sam Ervin (D-N.C.) – 69%

Lowest score: 31% (1956)

Highest score: 91% (1972)

Ervin in short: The trope originator for the “country lawyer”, Ervin by far had his greatest claim to fame as chairman of the Senate Watergate Committee, making him a hero among many Americans. Although perhaps the Senate’s most skilled legal opponent of civil rights legislation, he got points from liberals for his opposition to Everett Dirksen’s school prayer amendment as well as to “no knock” warrants for drug cases. However, such occasional liberal positions could serve to obscure his more conservative record in later years. Ervin retired from the Senate in 1974.

John C. Stennis (D-Miss.) – 69%

Lowest score: 37% (1983)

Highest score: 95% (1974)

Stennis in short: Stennis was a figure who was quite a bit more respected for his more legalistic approach than James Eastland’s on the subject of civil rights. He also was the author of the Senate’s first ethics code. Stennis was among the more conservative Southerners, but his record got a bit more moderate starting around the Carter Administration. Stennis managed to avoid a lot of trouble for his civil rights stances, something his colleague Eastland couldn’t end up living down. Stennis retired from the Senate in 1988, by which time he was 87 years old.

Donald Russell (D-S.C.) – 70%

Lowest score: 68% (1965)

Highest score: 71% (1966)

Russell in short: Donald Russell served during most of the Great Society Congress, and he wasn’t particularly notable as he filled in the vacancy caused by the death of Olin Johnston. He lost renomination to Fritz Hollings in 1966.

John McClellan (D-Ark.) – 72%

Lowest score: 38% (1956)

Highest score: 100% (1955)

McClellan in short: McClellan specialized in legislation combatting crime and racketeering and also famously chaired the McClellan Committee that investigated union corruption. He supported many measures (although not all proposals) limiting the power of organized labor. McClellan died in 1977, only a week after he publicly announced he would retire due to age and health.

James Eastland, D-Miss. – 73%

Lowest score: 43% (1957)

Highest score: 89% (1974)

Eastland in short: Among Southern senators, James Eastland was regarded as among the most racist of the group. Although not the worst major Mississippi politician on race during the Civil Rights Era (Governor Ross Barnett was worse), he became a face of Jim Crow. Eastland was certainly one of the more conservative of the Southern Democrats and was more willing to back proposals restricting organized labor than many were in the 1958 and 1959 debates on union reform. Once the political power of blacks in Mississippi’s Democratic Party was sufficiently developed, he opted not to seek another term in 1978.

Richard Russell, D-Ga. – 74%

Lowest score: 38% (1956)

Highest score(s): 100% (1955, 1960)

Russell in short: Richard Russell was the leader of the Southern bloc, and he was greatly admired by his Senate colleagues all-around. For instance, Republican Milton Young of North Dakota got in some hot water with his party in 1952 when he announced that if Russell won the Democratic nomination that he would support him for president. Russell was the lead tactician against civil rights legislation in the Senate. Although his earlier career reflected support for much of the New Deal, a lot of such politics had faded away by this period in history, with him opposing domestic liberal legislation frequently and opposing foreign aid. However, Russell did vote for the final version of Medicare in 1965. Russell’s heavy-smoking habit caused his 1971 death in office from emphysema.

Harry F. Byrd Jr., D, I-Va. – 86%

Lowest score: 69% (1980)

Highest score(s): 100% (1974, 1978)

Byrd Jr. in short: The son of Harry F. Byrd Sr. and his successor in the Senate, Byrd ultimately found given his strong conservatism and that Democrats would want him to pledge to support whoever the Democratic nominee for president would be in 1972, he instead ran for reelection as an Independent. Despite officially being an Independent, Byrd would continue to caucus with the Democrats until he opted to retire in 1982. He would be very much his father’s son, and this included being among the eight Senate “nay” votes to the Voting Rights Act extension in 1982, if perhaps a little more flexible.

William Blakley, D-Tex. – 86%

Blakley in short: William Blakley served briefly as an interim senator in 1957 after Price Daniel’s departure, and then again served in 1961 after Lyndon B. Johnson’s departure for the vice presidency. Blakley sought to finish LBJ’s term in 1961, but many liberal Democrats couldn’t stomach the solidly conservative Blakley and defected to Republican John Tower, who won.

A. Willis Robertson, D-Va. – 88%

Lowest score: 69% (1956)

Highest score(s): 100% (1955, 1957, 1961, 1962)

Robertson in short: Virginia’s delegation to Congress was among the most conservative, and possibly the most conservative of the whole South, and Willis Robertson was part of why. He was more fiscally conservative than most Southern Democrats, although even he doesn’t outmatch one of Virginia’s other senators. Robertson was also the father of televangelist Pat Robertson.

J. Strom Thurmond, D, R-S.C. – 91%

Lowest score: 25% (1956)

Highest score(s): 100% (1960, 1961, 1962, 1974, 1976)

Thurmond in short: In addition to being the candidate for president in 1948 on the State’s Rights Party (Dixiecrat) ticket, he also had the longest solo filibuster on a bill in history, when he spoke for 24 hours and 18 minutes against the Civil Rights Act of 1957. He also serves as a symbol for many: you might say he was the symbolic start of the long march of the South to the Republican Party when he switched in 1964. Thurmond was also known for his longevity, both in life and in office, serving until 2003, when he was 100.

Harry F. Byrd Sr., D-Va. – 93%

Lowest score: 81% (1958)

Highest score(s): 100% (1955, 1957, 1959, 1960, 1962)

Byrd in short: Harry F. Byrd, who had been Virginia’s governor in the 1920s and served in the Senate since 1933, had been one of the earliest Democrats to turn against FDR’s New Deal. His record on fiscal conservatism was pretty hard to beat and had a strong aversion to debt. Byrd also disagreed with Democrats on foreign aid and had even voted against both Greek-Turkish aid in 1947 and the Marshall Plan in 1948, a rarity for a Democrat. Byrd would maintain his power in Virginia through his machine as well as through his “golden silence”: he would not endorse a candidate for president. He also has some infamy for his push for “massive resistance” to desegregation, which lasted until 1959 but the effects of which lasted longer. Byrd would be strongly opposed to the New Frontier and Great Society. A brain tumor would force his retirement in 1965 and cause his death the next year. Per positions based on votes the ACA found to measure conservatism, Byrd is the foremost conservative among the Senate Democrats.

As you can see from this post, the range of Democrats varied a bit in the South, and although most would not be successes in today’s Democratic Party, many would perhaps be too moderate or liberal for today’s Republican Party.