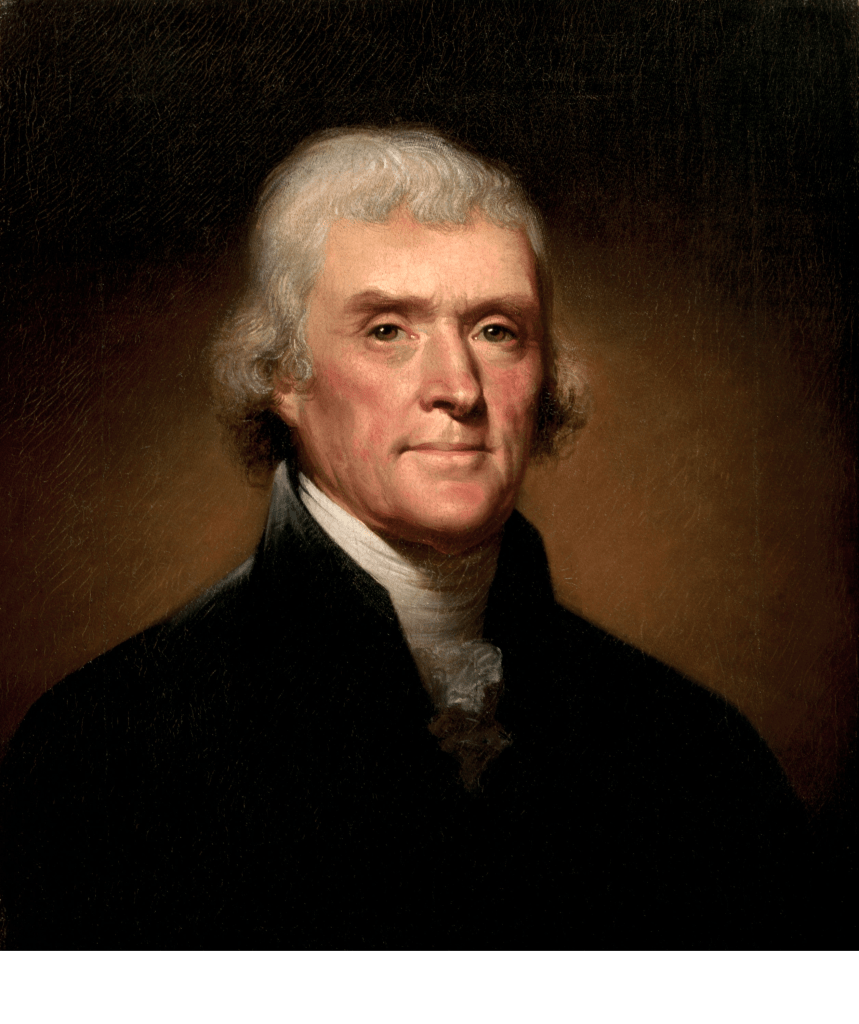

President John Tyler, whose nominees were most rebuked by a vote of the Senate.

At first, the people president-elect Donald Trump announced he would nominate after being sworn in seemed like the sort of picks you’d expect, Marco Rubio for Secretary of State or Elise Stefanik for Ambassador to the UN. However, three of his recent announcements have provoked shock, doubt, and opposition. These are Matt Gaetz for Attorney General, RFK Jr. for Secretary of Health and Human Services, and Tulsi Gabbard for National Intelligence Director. Gaetz has been a bomb-thrower in Congress for Trump and has made many enemies in the GOP for his leading role in the ouster of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), not to mention there was a House Ethics Committee report due to be released on his personal conduct before his resignation from the House. Kennedy has had a history of expressing many views that are out there, but most notorious have been his anti-vaccine stances. Furthermore, his personal record regarding marital fidelity makes Donald Trump look like a saint by comparison. Gabbard has in the past expressed support for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and has previously repeated Russian propaganda surrounding the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War. These announcements have certainly given some who would otherwise be supporting Trump nominations pause. Leading Senate Republicans have pledged that Trump’s nominees will go through the regular Senate vetting process as opposed to recessing the Senate thereby allowing Trump to install his cabinet for a maximum of nearly two years without Senate scrutiny. Believe it or not, only nine people have ever been rejected for a cabinet post by a vote of the Senate.

The first cabinet nomination in the history of the United States to be rejected was none other than Roger B. Taney, who would be most known as chief justice from 1836 until his death in 1864. Much like Trump is proposing to do, Andrew Jackson used a recess appointment to confirm Attorney General Taney as Secretary of the Treasury. However, as Treasury Secretary Taney was Jackson’s point man for the destruction of the Second Bank of the United States, which included advising transferring funds out of the bank and into state banks and authored a lot of President Jackson’s veto message (Encyclopedia Britannica). In retaliation, the Senate rejected continuing him in this position 18-28 in June 1834.

John Tyler’s Nominees

John Tyler has the dubious distinction of having the most cabinet nominees rejected by a vote of the Senate, with four getting rejected. This is certainly a least in part attributable to him considered by his party to be a rogue president. Indeed, him assuming the presidency instead of simply serving as acting president was considered questionable in his time, and some saw him as illegitimate. Yet, this precedent stuck. As a Whig, Tyler was dissenting on a lot of Whig policy, including vetoing restoring the Second Bank of the United States and vetoing two tariff increases. The defeated were Caleb Cushing for Secretary of the Treasury (who was voted on three times as Tyler stubbornly resubmitted his nomination twice), David Henshaw for Secretary of the Navy, James M. Porter for Secretary of War, and James S. Green for Secretary of the Treasury. The defeats of these candidates can broadly be attributed to President Tyler’s unpopularity.

Henry Stanbery

In 1866, the Senate confirmed Henry Stanbery as Attorney General for the Johnson Administration without fanfare or drama. However, relations between the Senate and Stanbery soured. He had backed President Johnson’s Reconstruction policy that gave no focus on rights for freedmen, and he had helped draft Johnson’s veto message of the first Reconstruction Act and on March 12, 1868 he resigned his post to join the defense team for President Andrew Johnson in the Senate’s impeachment trial. After Johnson was acquitted by one vote, he renominated Stanbery for his old post. The Senate, however, wasn’t having it, and his nomination was rejected 11-29 on June 2nd.

Charles B. Warren

In 1925, President Coolidge nominated Charles B. Warren to replace Attorney General Harlan F. Stone, who had been confirmed to the Supreme Court. Something to be understood about the Republican Party at this time was that although conservatives were strongly in the majority in the party, there was a staunch progressive wing and this wing in particular had clout in the Senate as they were able to team up with Democrats to oppose many policies of the Republican administrations of the 1920s. Warren was seen as too friendly to business interests, especially the “sugar trust”. The vote on this was going to be close, and Vice President Charles G. Dawes was going to be needed. Dawes thought he had time to take a nap at the Willard Hotel as he was told by the Senate leadership that a vote wouldn’t be held that day. However, the Senate abruptly decided to proceed to the vote…while Dawes was napping. Although Dawes was awoken and rushed to the Capitol to cast the tie-breaking vote, it was too late by the time he had arrived, as a senator had changed his mind to opposition with the vote failing 39-41. However, when the vote was held again on March 16th, it was rejected 39-46. President Coolidge was quite put off indeed by his vice president. This is also the last time that the Senate ever voted to reject a president’s nominee when the president’s party was in control.

Lewis Strauss

This rejection is the one that certainly has had the most public attention lately, given that it figured in the film Oppenheimer. Indeed, Strauss’s role in pushing of Oppenheimer out contributed to his defeat. However, there were other factors. Strauss’s competence was not in question, rather it was his polarizing personality that had become clear when he was a member and later chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission…while he had the full confidence and friendship of President Eisenhower, he made numerous enemies. Time Magazine (1959) described the variance of the views on him thusly, “Strauss, by the extraordinary ingredients of his makeup, is one to arouse superlatives of praise and blame, admiration and dislike. In the eyes of friends, he is brilliant, devoted, courageous and, in his more relaxed moments, exceedingly charming. His enemies regard him as arrogant, evasive, suspicious-minded, pride-ridden, and an excessively rough battler”. One of these enemies was Senator Clinton Anderson (D-N.M.), who led the charge against Strauss’s confirmation. Anderson made sure that committee hearings on Strauss went on for weeks, and he admitted that this was a strategy, “I thought if the committee members saw enough of him, he would begin to irritate them, just as he has me” (Time Magazine). Another factor was that Strauss, a staunch conservative, had repeatedly worked against public generation of power, supporting instead private industry. Although his nomination survived in committee by a vote of 9-8, this did not translate to confirmation, especially not in the strongly Democratic Senate. Strauss was rejected on a vote of 46-49, with 15 Democrats in support, and 2 Republicans in opposition. Strauss’s high level of defensiveness, an insistence on addressing every point of contention instead of admitting to a few errors, also harmed his nomination (Time Magazine).

John Tower

In 1989, President Bush nominated John Tower to serve as Secretary of Defense. Tower had served in the Senate from 1961 to 1985 as the first Republican to represent Texas since Reconstruction, and he had become an expert on national defense, serving as the chairman of the Armed Services Committee from 1981 to 1985. He had also served as the lead negotiator in the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks with the USSR and chaired the Tower Commission on Iran-Contra, which had issued a strongly critical report of the Reagan Administration. Tower was not known to suffer fools, and this made numerous senators on the Democratic side less than sanguine about his nomination. However, an unexpected opponent of his nomination came to testify before the Senate in Heritage Foundation’s Paul Weyrich. Weyrich opposed his nomination on the grounds of his moral character, stating, “I have encountered the senator in a condition lacking sobriety as well as with women he was not married to”, and adding to this Tower’s second wife, Lila Burt Cummings, alleged “marital misconduct” in her divorce filing (Los Angeles Times). The nomination became a highly partisan issue, and on March 9, 1989, Tower was rejected 47-53, with three Democrats (Dodd of Connecticut, Heflin of Alabama, and Bentsen of Texas) voting for, and one Republican voting against (Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas). The odd man out in support was Dodd, who although he denied it, it seems likely that he had Tower’s vote against his father’s censure in 1967 in mind. Tower’s defeat by vote of the Senate is the only one to have happened at the start of a president’s time in office.

I find it possible that the Senate rejects one Trump nominee in a vote, but more likely that a far more common event occurs: the nomination is withdrawn, either by Trump or the nominee him or herself. Indeed, there is a long list of announced nominations that were withdrawn during the first Trump Administration, including Andy Puzder for Secretary of Labor and Patrick M. Shanahan for Secretary of Defense. Count on some of those rather than a series of dramatic Senate rejection votes.

References

Conservative Tells of Seeing Tower Drunk: Senate Panel Hears Activist Oppose Defense Nomination. Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-01-31-mn-1492-story.html

Kelly, R. (2017, February 7). A Nap Got in the Way of the Last Tied Cabinet Vote in the Senate. Roll Call.

Retrieved from

https://rollcall.com/2017/02/07/a-nap-got-in-the-way-of-the-last-tied-cabinet-vote-in-the-senate/

List of Donald Trump nominees who have withdrawn. Wikipedia.

Retrieved from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Donald_Trump_nominees_who_have_withdrawn

Presidents Have Failed 8 Times to Win Cabinet Confirmations. Deseret News.

Retrieved from

https://www.deseret.com/1989/2/24/18796378/presidents-have-failed-8-times-to-win-cabinet-confirmations/

Roger B. Taney. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Retrieved from

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-B-Taney

The Administration: The Strauss Affair. Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6827665/the-administration-the-strauss-affair/