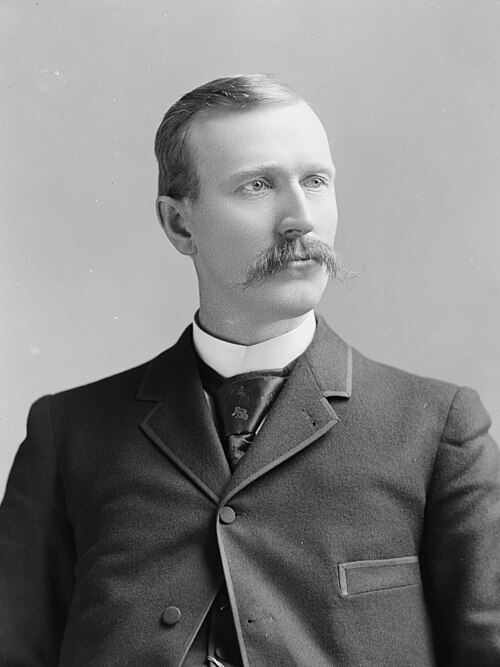

Electing a person to the Senate of a party is not always going to mean he or she will support everything their party does. Contrary to notions about RINOs (Republicans in Name Only) and to a lesser extent DINOs (Democrats in Name Only) , defections are less common than they used to be. However, with John Knight Shields (1858-1934), him being a party-line man was really never guaranteed.

Following in the footsteps of his father, Shields took up the practice of law, and for his first 12 years in practice he was a partner at his father’s firm. His good reputation resulted in his appointment as an officer who assisted judges with complicated legal cases, a position he served in for six years. In 1902, Shields was elected an associate justice of Tennessee’s Supreme Court, being elevated to chief justice in 1910. At that time, the Democratic Party had split into factions, with one of the groups accusing Governor Malcolm R. Patterson of attempting to intimidate Tennessee’s Supreme Court (Bristol Herald Courier). Shields won great respect in his stand for an independent judiciary, and he became thought of as a good choice for national office.

Shields was elected to the Senate by a combination of independent Democrats and Republicans, and thus he was not really ever going to be someone’s man. Indeed, he could be personally a bit prickly. While Shields supported a good deal of President Wilson’s New Freedom legislation, his independence would not put him in good stead with him. He was a defender of state’s rights, and this manifested in his opposition to Prohibition and women’s suffrage. Shields also believed that the creation of the Federal Water Power Commission, championed by Wilson, was an unconstitutional intrusion on the states (The New York Times). However, the issue that would cause such a rift between him and the president and many fellow Democrats was yet to come.

In 1918, his renomination appeared in doubt, and there was a rumor that President Wilson was going to write and a publish letter that he was no friend of his administration, and in response fellow Senator Kenneth McKellar begged Wilson not to write it, and it was not written (Hill, 2019). Despite this letter not being written, Shields was keen on continuing to be independent from and even hostile to the president. After the election, he even snapped that Wilson and his secretary Joseph Tumulty could go to hell (Hill, 2019). Shields came out strongly against the League of Nations, at least President Wilson’s version of it and he backed Henry Cabot Lodge’s (R-Mass.) strong reservationist substitute. Shields considered himself acting true to the principles of the nation and the Democratic Party, including Wilson during the 1916 campaign (Bristol Herald Courier). Such a dissent was to Wilson a sin that could never be forgiven, especially after he had held his pen so the senator could be reelected. Shields also charged that selfish interests were at work for the League of Nations, stating, “Great capitalists who desire to speculate in the deprecated bonds of the bankrupt nations of Europe and dealers in cotton and food products, who desire to exploit those countries for selfish purposes and wanted the United States as provided in the League of Nations to stabilize those governments and make their bonds and contracts valid, have spent over a million dollars under the auspices of the League to Enforce Peace in organizing branches of their league, paying public speakers and subsidizing newspapers to have the treaty ratified” (Hill, 2020).

During the Harding and Coolidge Administrations Shields had reverted a bit back to party loyalty, including opposing the tariff increases and income tax reductions under Harding. Although supportive of electrifying the Tennessee Valley area using the Muscle Shoals properties, he was supportive of it being done by private (by Henry Ford), rather than public means. President Warren G. Harding seriously considered nominating Shields to the Supreme Court in 1922 as his pick of a Democrat, but had wanted to pick a man under 60 and due to a misprint Harding believed that he was younger. He was in truth 64, and Harding instead selected the 56-year-old Pierce Butler.

Although Wilson had not written that letter that would have ended Shields’ career in 1918, he did write it and make it public before the 1924 primary. He also had opposed bonus legislation for World War I veterans, which was very popular and seen as a patriotic thing to support. Although Wilson died before he could see Shields get beat, Wilson’s letter and death did impact it. His primary opponent, Lawrence Tyson, charged that Shields’ opposition sped up Wilson’s decline and death (Bristol Herald Courier). Wilson did get his revenge from beyond the grave, as the Democrats nominated Lawrence Tyson to be the next senator. Shields’ DW-Nominate score was a -0.156, which placed him among the more conservative Democrats. He chose to retire after this loss and although President Coolidge offered him a post on the Federal Trade Commission in 1926, he preferred to spend the rest of his days at his beloved family estate of “Clinchdale” in Grainger County than return to Washington D.C. In 1934, tragedy struck when Shields’ wife died, and he was so distraught that his health broke down, dying two weeks later on September 30th at the age of 76.

References

Ex-Senator John K. Shields Succumbs. (1934, October 1). The Bristol Herald Courier, 1.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/586529503/

Hill, R. (2019, March 24). The 1924 Senate Race in Tennessee, I. The Knoxville Focus.

Retrieved from

https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/this-weeks-focus/1924-senate-race-tennessee/

Hill, R. (2020, January 20). Tennessee and the League of Nations, V. The Knoxville Focus.

Retrieved from

https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/this-weeks-focus/tennessee-league-nations-v-2/

John K. Shields, Ex-Senator, Dies. (1934, October 1). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Shields, John Knight. Voteview.

Retrieved from