This month, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 turned 60; Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill into law on August 6th. Thus, I am covering the subject of the process of its passage.

Selma

The violence seen on national TV in Selma, with non-violent protestors being beaten by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, shocked the nation and increased calls for action on voting rights. Further pushing public opinion was a racist mob beating Reverend James Reeb to death at Selma and the murder of Viola Liuzzo by members of the KKK. Although the previous year’s landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 had a section for voting rights, it was not regarded as sufficiently strong during the 1964 election. Although it was clear that in the Great Society Congress action would be taken, the question was which course would be taken?

A Harsh Bill

After these events that got worldwide press coverage, President Johnson instructed his Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to craft “the goddamndest, toughest voting rights act that you can” to counter the situation in the South. The Johnson Administration’s measure, backed by House Judiciary Committee Chairman Emanuel Celler (D-N.Y.), contained the following provisions:

. A suspension of literacy tests for five years in areas where less than 50% of the eligible population was registered or voted in the 1964 election.

. Federal examiners to register and enforce the right to vote for all citizens unable to exercise the right.

. Nationwide prohibition on measures that are discriminatory in voting practices.

. Outright ban on the poll tax for voting in state and local elections.

. Language assistance for voters who were not proficient in English.

. A “preclearance” provision requiring covered states and localities to get their election changes approved by the US Attorney General. This was one of the most controversial provisions.

The Senate

The advocacy for a strong Voting Rights Act was led by Senator Phillip Hart (D-Mich.), the bill’s manager, and was aided in efforts to strengthen the bill by Hiram Fong (R-Haw.), Birch Bayh (D-Ind.), Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.), Edward Long (D-Mo.), Joseph Tydings (D-Md.), Jacob Javits (R-N.Y.), Quentin Burdick (D-N.D.), and Hugh Scott (R-Penn.). The opposition to the measure would normally be led by Richard Russell (D-Ga.), but he was under the weather so the bulk of the work against came from Allen Ellender (D-La.), with help from Sam Ervin (D-N.C.), James Eastland (D-Miss.), John Stennis (D-Miss.), Herman Talmadge (D-Ga.), Lister Hill (D-Ala.), and John Sparkman (D-Ala.). The Senate’s party leaders, Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.) and Everett Dirksen (R-Ill.), were instrumental in crafting a bill that could get widespread support.

Whither Poll Taxes?

One controversy surrounding the Voting Rights Act was how the law should address poll taxes. The original bill had a provision that outright banned state and local poll taxes, but the bill was changed in the Senate on this count. A key vote on the Voting Rights Act was regarding Senator Ted Kennedy’s (D-Mass.) amendment to retain the bill’s explicit ban on the poll tax for states and localities. This amendment was opposed by President Johnson, Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, and Minority Leader Everett Dirksen. Mansfield and Dirksen crafted a substitute that declared that poll taxes were contrary to the right to vote and directed the U.S. Attorney General to initiate lawsuits against poll taxes in states and localities, believing that courts would act against poll taxes. Kennedy’s amendment failed on May 11th, 45-49. Courts would act as Mansfield and Dirksen anticipated in striking down poll taxes. The most unusual vote was from Louisiana’s Russell Long, who voted for this amendment but voted against the Voting Rights Act.

Support for the Voting Rights Act:

George McGovern (D-S.D.), future presidential contender, stated, “For more than one hundred years this basic right [voting] has been denied to large segments of the American citizenry, solely because of the color of their skin. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 will secure that right. It will be passed by an overwhelming margin, because there is broad agreement on the part of the American people that to deprive the American Negro of the right to vote is to deprive all of us of the essence of our heritage and democracy” (11750).

Jacob Javits (R-N.Y.), one of the Senate’s leading liberals, justified support of the Voting Rights Act given numerous instances of denials of the vote, stating, “The fundamental basis for the bill is the factual finding of Congress that there have been such widespread denials of the fundamental right to vote in so many broad areas of the Nation as to require the application of remedies in order to implement the 15th amendment” (11740).

Milward Simpson (R-Wyo.), while acknowledging the bill was a tough measure, he also said, “Time and time again legislation has been before the Congress which is proposed with the view toward bringing the right to vote to all citizens. I am ashamed, and all Americans should be ashamed, that this right has not been one of those cherished rights guaranteed to all citizens, regardless of race or color” (11746). Simpson’s support is a significant development as he had been one of six Republican senators to vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 the previous year.

Opposition to the Voting Rights Act:

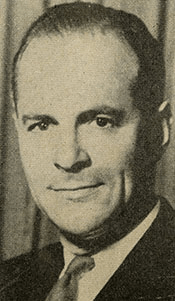

James Eastland (D-Miss.), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee who had made his committee the “graveyard” for civil rights legislation, asserted that with the Voting Rights Act “we are entering an era of absolute government. The bill is a major step in that direction. It will destroy the system of government that we know now. We are destroying it under the whiplash of Martin Luther King and others of that ilk” and cited Article I, section 2 of the Constitution to justify opposition (11735).

John Sparkman (D-Ala.), who was the Democratic Party’s pick for vice president in 1952, opposed the bill on nine counts, including what he found to be unequal protection of the laws, a distortion of the proper relationship between federal, legislative, and judicial functions of government, and that the bill was sectional (11727-11728).

John Tower (R-Tex.) stated his sympathy with the aim of the bill and acknowledged that the federal government does have the authority to enforce the 15th Amendment, he objected to way it was to be achieved, holding, “Mr. President, the mathematical guilt formula to be so unjustly hung upon several States and counties, is arrived through the highly questionable assumption that literacy tests and lower voter participation always means discrimination. Other objective, basic assumptions that lack of participation in certain elections may be due to a strong one-party system, voter apathy toward one or more candidates, or even bad weather, are completely ignored” (11751).

Whither Literacy Tests?

The Voting Rights Act suspended literacy tests for five years in covered jurisdictions, and literacy tests would later be banned permanently. The core debate surrounded the question of whether literacy should be a consideration or if literacy tests should remain but with standards as to what constitutes literacy. Republicans, such as William McCulloch (R-Ohio), thought that a 6th grade education was sufficient proof of literacy. This standard would be placed into the Republican substitute of the bill. Another controversial proposal was by Rep. Jacob Gilbert (D-N.Y.), which permitted people to vote if they proved literate in a language other than English that was taught in their school. This amendment, primarily geared towards Puerto Ricans, was rejected 202-216. The bill passed 77-19 on May 26th, but the measure still had to get through the House.

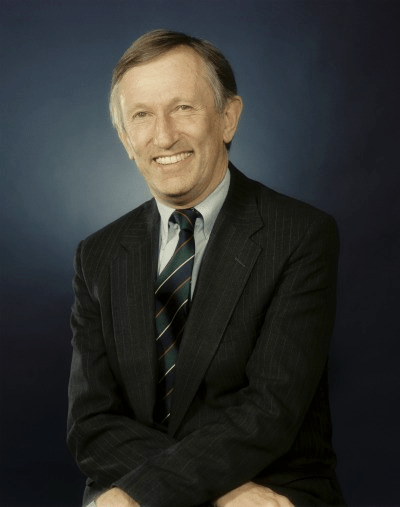

Proposed Republican Substitute

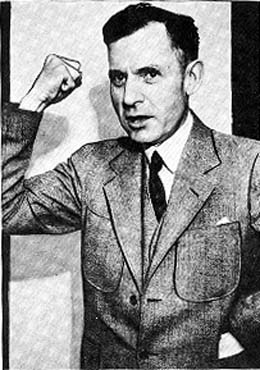

House Republicans had an alternative voting rights plan, backed by Minority Leader Gerald Ford (R-Mich.) and William McCulloch (R-Ohio), ranking Republican on the Judiciary Committee. This substitute aimed to balance out the interests of state’s rights and civil rights, by making enforcement on a by county basis. It established a 6th grade education as proof of literacy (thus allowing literacy tests for individuals who had not graduated from 6th grade), retained the ban on poll taxes and would also cover Texas under the Voting Rights Act, which President Johnson, who continued to look out for the interests of his home state, didn’t want. Although not exactly a prince of a state on the subject of voting rights, it was known that the conditions of Texas were not like those of the Deep South. Rep. William McCulloch critiqued the Celler (D-N.Y.) version of the bill, and did so on conservative terms, calling the automatic trigger mechanism in the bill “pure fantasy – a presumption based on a presumption” and considered the committee bill an attack on the ability of the states to determine voter qualifications (Reichardt). This substitute had a key foe in liberal stalwart Frank Thompson (D-N.J.), who argued, “…I oppose the Ford-McCulloch substitute amendment because it does not reach down into the heart of the problems were are trying to eliminate. It is no fiction that “tests and devices,” a key phrase in voting and registration legislation, are being used to restrict the franchise. A serious defect of the Republican leadership substitute is in its requirement that Federal examiners administer tests to applicants with less than six grades of education. This requirement would serve to continue into the present and the future a double standard of testing – the very evil we are attempting to eliminate. Negroes would be tested by the examiners on the basis of the standard set forth in the substitute amendment – completion of six grades or passing of the State literacy test. At the same time, whites would be applying for registration to the State or local registrar, who would presumably do what he has always done – register whites on the basis of their white skin rather than on the basis of any educational achievement or passage of any test” (16228). Most fatal to this proposed substitute, however, was the embrace most Southern Democrats gave this substitute, even if they did not intend to support it on passage. This signaled to the liberal 89th Congress, already predisposed to support President Johnson on domestic policy, that the Republican substitute was weak. Rep. Harold Collier’s (R-Ill.) effort for the House to adopt the Republican substitute as well as Rep. Robert McClory’s (R-Ill.) amendment failed 171-248. Interestingly, a few opponents of the Voting Rights Act voted against this substitute, including some from Texas, as this version would have covered Texas. One Republican proposed amendment that did pass, however, was the Cramer (R-Fla.) anti-voter fraud proposal, which passed 253-165 with all Republicans in support.

House Supporters:

Ed Roybal (D-Calif.) cited recent violent events as justification for the Voting Rights Act and considered the measure a “clear, practical, effective, and legislatively responsible way to enable citizens to vote without the fear or threat of discrimination” (16280).

Majority Whip Hale Boggs (D-La.) stated, “I wish I could stand here as a man who loves my State, born and reared in the South, who has spent every year of his life in Louisiana since he was 5 years old, and say there has not been discrimination. But unfortunately it is not so” and went on to state, “I shall support this bill because I believe the fundamental right to vote must be part of this great experiment in human progress under freedom which is America” (U.S. House of Representatives). His announcement of support was a big deal given that he had previously opposed all civil rights measures save for the 24th Amendment.

Jonathan Bingham (D-N.Y.) stated his support for the Celler (D-N.Y.) version, regarding the Ford-McCulloch substitute as much weaker (16273).

Paul Findley (R-Ill.) spoke in support of the bill, citing the Lincolnian heritage of the Republican Party as Lincoln’s Illinois hometown of Springfield being in his district, and praised Gerald Ford’s (R-Mich.) recent appointment of Frank Mitchell, the first black page of the House (16272).

Charles Goodell (R-N.Y.) stated his reserved support for the Celler (D-N.Y.) version of the Voting Rights Act and voiced his preference for the Ford-McCulloch substitute. He regarded the Celler version as “unnecessarily punitive” and critiqued only applying the Voting Rights Act to seven states, noting Texas being absent from coverage, but said he would vote for the Celler bill (16273).

William F. Ryan (D-N.Y.) wanted a measure that did more, and cited deprivations he witnessed as a civil rights activist of freedoms of speech, assembly, and press, but acknowledged that this measure was the furthest the federal government had gone so far (16265).

Frank Annunzio (D-Ill.) praised the bill and also cited the murders of civil rights activists Reverend James J. Reeb and Viola Liuzzo as being bad for the US’s image abroad (16272).

House Opponents:

John Dowdy (D-Tex.) condemned the suspension of certain state laws surrounding election policy and considered suspensions as characteristic of martial law or the tyrannical regimes of Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, but not America (16268).

Glenn Andrews (R-Ala.) asserted that the Voting Rights Act itself was a form of discrimination against seven states, Alabama being among them, and cited Article II, section 1, clause 2 that states have the right to set voter qualifications (Congressional Record, 16274).

James Broyhill (R-N.C.) stated his opposition to the Celler version of the Voting Rights Act, but said that if the Ford-McCulloch substitute would be adopted that he would vote for the bill on passage (16270).

W.J. Bryan Dorn (D-S.C.) condemned the embrace of the Voting Rights Act as Congress “being forced to bow and subvert itself to the will of the mob” and that the legislation was “punitive”, “vindictive and sectional”, and “evil” (16268).

The House passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 333-85 on July 9th.

There are a few things to note about the votes on the Voting Rights Act. First, opposition was almost entirely among Southern politicians. There were only seven legislators outside of the South that opposed the Voting Rights Act on both initial passage and the vote on the conference report: Senator Robert Byrd (D-W.V.), Republican Representatives H. Allen Smith of Glendale and James B. Utt of Tustin (Orange County), California, Republican George Hansen of Pocatello, Idaho, Republican H.R. Gross of Waterloo, Iowa, Democrat Paul C. Jones of Kennett, Missouri, and Republican Robert C. McEwen of Ogdensburg, New York. Also of note was the abstention of Democrat Adam Clayton Powell Jr. of Harlem, New York. Although in truth of disputable racial identity as he was of mixed racial origin (he had blue eyes) and thus could have passed for white, Powell identified himself as black, and a radical at that, and abstained as he thought the bill was not strong enough. He held that this as well as the 1966 civil rights bill was a “phony carrot stick” for black middle class (CQ Press). There were also notable differences between the House and Senate versions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, including the House version’s outright ban of state and local poll taxes. The final version hammered out by the conference committee kept the Senate language on state and local poll taxes, thus they would be challenged in court, adopted the Senate’s provision that waived requirements for English literacy to vote in certain cases, and adopted the stronger triggering formula in the House bill as opposed to the Senate bill which allowed certain escape clauses (Reichardt). The net impact of the conference committee’s bill does seem to have been to make the bill stronger. The only senator who switched on the Voting Rights Act’s conference report was Florida’s George Smathers, who went from voting against to voting for, while in the House there were a few new Republican votes against, such as Paul Fino (R-N.Y.) over the English literacy provision but there were also some new Republican votes for, such as all three of Tennessee’s Republican representatives. In the South, there were a few Democrats who flipped from opposition to support, such as A.S. Herlong (D-Fla.) and George Mahon (D-Tex.). Contrary to what GovTrack and Voteview will tell you, one of these switches was not Watkins Abbitt (D-Va.). Through an error they mix up Abbitt’s vote with that of E. Ross Adair (R-Ind.), who voted for both the House and conference version of the Voting Rights Act. The result was a highly effective law that increased black participation in politics in the South, although it would take a few election cycles for the full power of their votes to be realized.

References

Controversies Surround Rep. Adam Clayton Powell. CQ Almanac 1966. Congressional Quarterly Press.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal66-1301925#_=_

Majority Whip Hale Boggs’ Support of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. US House of Representatives.

Retrieved from

https://history.house.gov/HistoricalHighlight/Detail/36267

Reichardt, G. (1975). The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (C): Congress and the Voting Rights Act. Harvard University.

Retrieved from

The Senate Passes the Voting Rights Act. U.S. Senate.

Retrieved from

https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Senate_Passes_Voting_Rights-Act.htm

Voting Rights Act of 1965. Congressional Record, 11715-11753.

Retrieved from

Voting Rights Act of 1965. Congressional Record, 16207-16286.