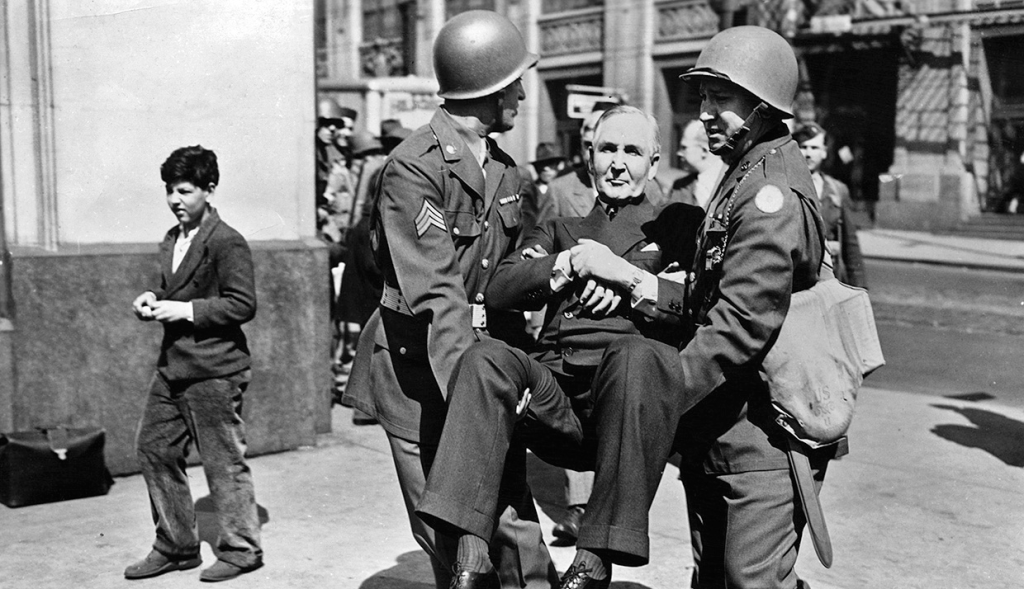

On August 31, 1940, Farmer-Labor Senator Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota, an outspoken non-interventionist, boards a plane from Washington D.C. to Detroit. Unfortunately for him and everyone on board, this is Flight 19 of Pennsylvania Central Airlines, which crashes near Lovettsville, Virginia, killing all on board in the worst air disaster in US history at the time. It is up to Republican Governor Harold Stassen to appoint a successor. Rather than pick any sort of established figure in Minnesota politics, he picks a 34-year-old journalist with no political experience in Joseph Hurst Ball (1905-1993) to finish Lundeen’s term.

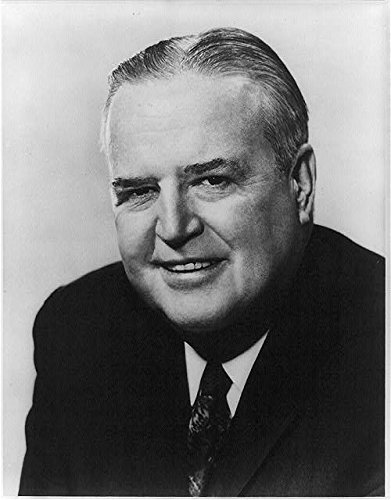

Senator Ball

Ball is the youngest senator at the time and indeed, he is one of the youngest in American history. Where he will stand on the issues is a mystery as he has no track record and did not run an election campaign. However, Ball clears this up when in his first speech he calls for aid to Great Britain. This goes against the political mood of Minnesota, and his interventionist stance makes him highly unpopular for a time. In 1941, he is one of only two officials elected to Congress from Minnesota to vote for Lend-Lease, the other being the Iron Range’s Representative William Pittenger. Ball’s independence won him plaudits after the attack on Pearl Harbor. 1942 is a good year for Republicans, and Ball wins a four-way contest for a full term with 47% of the vote.

In 1943, Ball was tapped to the Truman Committee to investigate wartime expenditures. This committee, strongly bipartisan and full of people that Truman held in high esteem, was quite successful in its aims of bringing accountability to war spending and saving money. Although independence on foreign policy characterizes his career, so does his push against the power of labor unions. Ball, for instance, was a strong supporter of outlawing closed shops (The Vincennes Sun-Commercial). However, what he valued most was foreign policy, and this motivated a decision that stunned his party.

On October 23, 1944, Ball delivered an “October Surprise” to the Dewey-Bricker campaign when he publicly stated that he would be voting for the reelection of President Roosevelt, stating that Dewey had not presented the public with “a workable, constructive program on the domestic issues of taxation and labor relations” and had been too willing to cater to non-interventionists (The New York Times). Although he had not been uncritical of the Roosevelt Administration on the issues, he found its foreign policy preferable. Dewey’s running mate, Bricker, was most disappointed in this development. He stated that he had made a “grievous mistake” and was “doing a great disservice to his country” (Springfield Evening Union).

In 1945, Ball signaled a willingness to cooperate with Roosevelt in his support of the confirmation of Henry Wallace as Secretary of Commerce. However, his record on domestic issues proves quite to the right, such as his consistent support for private ownership as opposed to public ownership and his opposition to price controls.

During the 80th Congress, Ball played a major role in the crafting of the Taft-Hartley Act, which ended the national closed shop. His independence on foreign policy took a rather unexpected turn when on March 13, 1948, he was one of 17 senators to vote against the Marshall Plan, a stance that when Republicans took it, it was mostly out of a sense of non-interventionism. Ball had sponsored an unsuccessful amendment to create an 11-member western military alliance outside of the UN to counter Russian aggression (Daily News). His motives for opposition seem to have been a mix of wanting to take a stronger line against communism and balking at the considerable cost. This issue, in addition to his support for the Taft-Hartley Act, were key points that Hubert Humphrey used in his campaign against him.

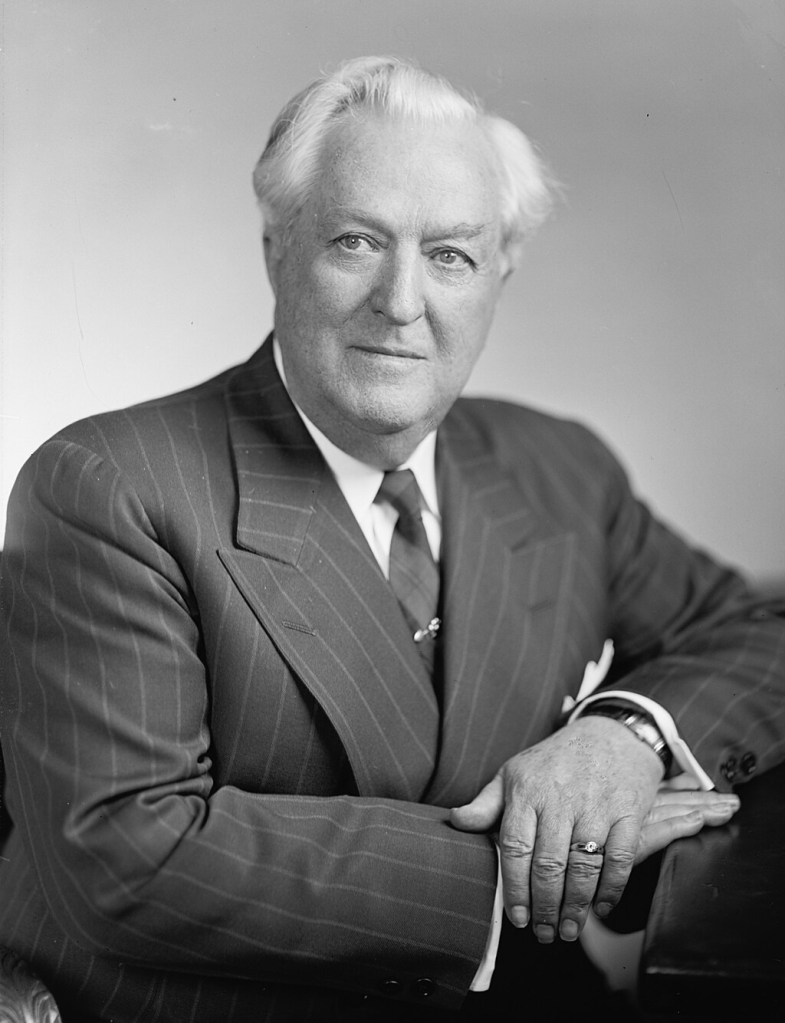

Given Humphrey’s popularity as mayor of Minneapolis and his rousing pro-civil rights speech at the Democratic National Convention for the Democratic Party to shift its focus from state’s rights to human rights, he was a favorite to win. Ball may have had a chance if Henry Wallace’s campaign had decided to endorse a third-party candidate and for a time it looked like former Farmer-Labor Governor Elmer Benson would jump into the race (Wilson). If so, the left would have been divided in Minnesota, improving Ball’s chances at another term. However, by late October it was abundantly clear that Humphrey was an easy favorite, and indeed the chances of the Democratic Senate candidates were rising (The Morning Union, 6). This gain in Democratic odds in the Senate really ought to have told many political observers and pundits that President Truman was much better off than commonly thought. Humphrey ran away with the election, winning by 20 points, becoming the first Democrat to win a popular election to the Senate from Minnesota. Humphrey’s election would be part of a general shift in Minnesota politics away from its Republican history. Ball’s DW-Nominate score was a 0.241, indicating moderate conservatism, and he agreed with the liberal Americans for Democratic Action 38% of the time during the 80th Congress.

Ball would never hold elected office again, but unlike the man who appointed him, he would also never run for elected office again. He continued his career as a journalist and in the 1950s he would come to the defense of some individuals his former colleague, Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wis.), accused of disloyalty. Ball also spent some time as an executive in the shipping industry, retiring in 1962. Up until his declining health forced him to live in a retirement home, he raised Black Angus cattle in Front Royal, Virginia. Ball died of a stroke on December 18, 1993, outliving many of his contemporaries, including Hubert Humphrey by 15 years. It is clear to me that Ball was an individual for who party loyalty was not a good argument to persuade him to vote in any way and one who could be counted on to vote his conscience. I appreciate such people in politics and yes, with such people there are bound to be disagreements, but they are disagreements in good faith and produced by the conviction of the individual rather than by outer pressure or a supposed obligation.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Ball Holds Dewey Straddles Issues. (1944, October 27). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Closed Shop Fight Heading for Showdown. (1946, November 12). The Vincennes Sun-Commercial, p. 1.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/1052636475/

Democrats and Republicans Contest for Senate Control. (1948, October 22). The Morning Union, 1, 6.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/1068535337/

GOP Senator Ball To Vote for F.D.R. (1944, October 23). Springfield Evening Union, 1.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/1067489763/

Montgomery, R. (1948, March 14). ERP Assured; Senate Beats Substitute Plan. Daily News, 236.

Retrieved from

https://www.newspapers.com/image/445828367/

Wilson, L.C. (1948, October 4). Wallace Hopes Begin to Skid. The Stockman’s Journal, 3.

Retrieved from