I recently found a most interesting source on the 1960 election, and it is Congressional Quarterly’s breakdown of the election by district, which tells a fascinating story of the politics of the day. The politics of 1960 stand as a great contrast to contemporary politics. The parties were far more ideologically diverse, although Democrats still got more of the black vote than Republicans, Republicans could still get a significant minority, and both parties were trying to appeal to the white South. Republican Richard Nixon and Democrat John F. Kennedy compared records during the campaign to make their cases of who was the most experienced. Today, experience is often seen as a liability in Washington, as voters regularly clamor for outsiders. Only two candidates who were perceived as establishment rather than outsiders won presidential elections since 1976: George H.W. Bush in 1988 and Joe Biden in 2020, and neither of them served a second term. This was a remarkably close election, and victories could be seen for both parties in all regions of the nation. Kennedy’s top three states paint a varied picture in Rhode Island, Georgia, and Massachusetts. Richard Nixon won in some areas that are out of bounds for Republicans today, such as Portland, Oregon. Although San Francisco was Democratic, it was not as Democratic as it is today, and one of its two House seats was held by a Republican with Nixon coming close to winning that district.

Although one must acknowledge the complexities of politics in 1960 that we don’t see today, such as a substantial contingent of Southern Democrats voting more or less conservative, one sees a considerable difference between Nixon’s electoral performance and the Republicans down ticket. This was highly noticeable in the South, and there were numerous Southern districts that were overdue for a flip to the GOP. Some were predictive of future elections; Alabama’s 9th district (Birmingham), represented by George Huddleston Jr., was the only district Nixon won in the state, and in 1964 the district would flip to the GOP. Same goes for Arkansas’ 3rd district based in Fort Smith, in 1966 that district would flip to the GOP and do so for good. In Florida, Voters in half of its Congressional districts voted for Nixon, but the only House Republican elected was William Cramer of St. Petersburg. Although North Carolina voted for Kennedy, 7 of 12 of its House districts would have elected a Republican if the district vote was the same for president and Congressional candidates, while in reality only Charles Jonas of the 10th district was elected. In Tennessee, 5 of 9 of the districts voted for Nixon as did the state, yet only the standard two Republicans from the 1st and 2nd districts were elected to Congress that year. Republicans were gaining strength in suburban areas of the South, while Democrats retained their large advantage in rural areas. For instance, in Florida’s 3rd district, constituting the state’s western panhandle, Kennedy got the highest percentage of the vote of any of the districts. This area was the most culturally Deep South of any of Florida’s districts, and it would elect Democrats until 1994. This also happens to be the area that Matt Gaetz represented until last year. Among Southern states, Georgia was a great exception to the South being a battleground area, as Kennedy was spectacularly popular in the state, having an even better performance there than in his home state of Massachusetts and winning all districts, putting him narrowly over the top in the Southern vote. Indeed, the Southern vote came out 51-49 for Kennedy. This would make Georgia’s vote for Barry Goldwater in 1964 all the more jarring. However, something to note is that the black vote for Kennedy was considerably stronger than the Southern vote, which was informative for the Democratic Party as to where its future was, with him winning 68% of the demographic. A Democrat getting a figure as low as 68% in the black vote is now unheard of.

This map is also roughly predictive of where Kentucky and Oklahoma are now. In the former, Democrats only won two districts, the 1st based in Paducah which came the closest in the state to seceding during the War of the Rebellion, and the 7th, represented by liberal Carl Perkins. In the latter, only the 3rd district with Carl Albert, known as “Little Dixie”, voted for Kennedy. Yet, both states only sent one Republican to Congress from the House, although Kentucky strongly voted to reelect Republican Senator John Sherman Cooper, a popular maverick. On the state level, Missouri was strongly Democratic with both its senators and 9 out of 11 of its representatives being Democrats, but Nixon won 7 of 11 of its districts, only losing in the districts based around St. Louis and Kansas City.

In the West Coast, Nixon outperformed down ticket Republicans in California and in Oregon, winning all districts in the latter. However, Oregon’s status as a Republican state was going downhill, as President Eisenhower’s land use and private power policies were not popular among the state’s voters. Even though the state’s voters went for Eisenhower twice, Republicans in the state took a beating for it, and they since haven’t gone back to the level of power they had before the Eisenhower Administration. Washington, on the other hand, sent a curiously mixed delegation to Congress: 5 of its 7 representatives were Republican yet both of its senators were Democrats, and the state narrowly pulled the lever for Nixon. Republicans outperformed Nixon in the state, but this wouldn’t last, and by 1968, the state would be down to two House Republicans and Nixon would lose it.

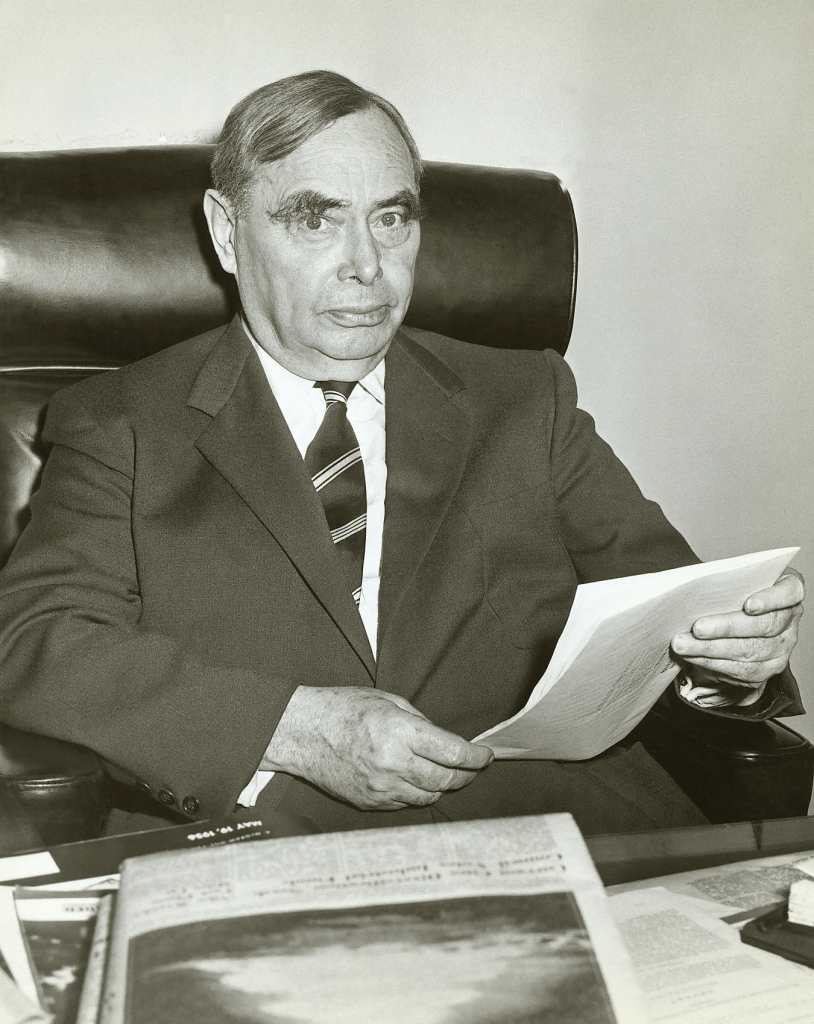

Former House Speaker Joe Martin (R-Mass.), who hung on despite Kennedy winning his district on account of his status as an institution in his district.

Although Nixon outperformed Republican candidates in the Midwest and Border States and especially the South, Congressional Republicans outperformed Nixon in eight states: the aforementioned Washington, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. In Pennsylvania, prominent moderate Republican William Scranton would be elected from the Scranton-based 10th district while Nixon lost. Nixon way outperformed Republicans in the South, as voters were used to the idea of splitting their tickets. In Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy won in all of the Congressional districts and the state was his third best, but this did not translate into any defeats in the 6 House seats Republicans held nor did it result in the defeat of moderate Republican Senator Leverett Saltonstall, whose politics were pretty much perfectly calibrated for a Republican in the state; conservative enough to not tick off the GOP base but also liberal enough for him to have considerable crossover appeal. Another example of a successful Republican in the Bay State was former Speaker of the House Joe Martin, who had been in office since 1925 and who was holding on in a district that had been starting to vote Democratic as he was an institution, the many favors he had done for his constituents, and his increasingly moderate voting record. The performance of John F. Kennedy in 1960 in Massachusetts can be seen as predictive for the long-term of the state, which since 1997 has had an entirely Democratic delegation to Congress save for 2010-2013, when Republican Scott Brown served in the Senate. The only states in which Kennedy had a better performance were Georgia and Rhode Island, which reflects the highly dual nature of the Democratic Party at the time. Indeed, both candidates sought to appeal to black and Southern white votes. The House leadership team was Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas and Majority Leader John W. McCormack of Massachusetts in what was known as the “Austin-Boston Connection”. Delaware was an interesting case, as although it gave Kennedy a victory, Republican Cale Boggs defeated Democratic Senator J. Allen Frear for reelection, but at this time Boggs was viewed as more liberal than Frear, who had often frustrated Democratic leadership with his conservative voting record. Delaware’s sole Congressman, liberal Democrat Harris McDowell, was reelected. Nixon also handily won Vermont, which at this time had the longest streak of voting for Republicans for president, but it should be noted that this would be broken in 1964 and neither its senators nor sole representative were of the conservative wing of the party.

The Strange Cases of Alabama and Mississippi

The South was competitive ground in the 1960 election, but there was a complication: the State’s Rights Party. They ran uncommitted slates of electors in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Although not enough traction was gained for a difference to be made in Louisiana, they had impact in Alabama and Mississippi. Although they were far from the only Jim Crow states, they were the most disaffected by the civil rights movement and this impacted how the states were voting this year. Alabama had the single strangest way of voting of any state that year, as people who voted Democratic were clearly voting for a slate of electors, with some pledged for Kennedy and others not pledged, for president. The percentage of the vote tabulated in Alabama thus doesn’t technically go to Kennedy, rather Democratic electors. The Democratic electors won, and Alabama’s electoral vote was split 6 for Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia and 5 for Kennedy. A controversy remains to this day as to whether Nixon could be said to have won the popular vote in a plurality in Alabama because of this split.

Mississippi was the only state that year to not cast electoral votes for either Nixon or Kennedy, with the state being won by “unpledged electors”, who cast their votes for Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia. Kennedy got the lowest percentage of the vote here of any state, and Mississippi would go even further in its rejection of the national Democrats in the 1964 election with 87% of its voters (at the time nearly all white) voting for Goldwater. Kennedy’s Catholicism in many areas of Mississippi was seen as suspect, and they were generally aware that he was a liberal, which didn’t play well there.

Alternative Scenario: Presidential and Down Ticket Votes Mirror Each Other

An interesting conclusion can be drawn if we present an alternate scenario in which the Republican Party down ticket is just as popular as Nixon: Kennedy would have faced a Republican House with Republicans getting 227 seats as opposed to the Democrats’ 207, although what happens in Alabama and Mississippi in this scenario is quite disputable. While the Senate would have stayed Democratic given the drubbing Republicans suffered in 1958, but they would have gained four seats instead of two. This would have made Kennedy’s presidency more difficult. The popularity of down ticket candidates for the Democratic Party can be attributed to there being many Democratic voters willing to split their tickets. Indeed, ticket splitting was far stronger in 1960 than it is today, although this is because we have what are called ideologically responsible parties with a lot less ideological wiggle room. Furthermore, back in 1960, Democrats had a 17 million voter registration advantage, far more than they have today. I have also included below a sheet that makes the data a bit easier to read than CQ’s source. Bold italics indicate Republican Congressional winners while D and R designations indicate the presidential winner of the district. Alabama is asterisked due to its unique way of counting Democratic votes, thus percentages reflect votes for Democratic electors rather than Kennedy.

1960 Election Results:

References

1960 Official Vote In Each State, All Congressional Districts. CQ Almanac 1961. Congressional Quarterly Press.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal61-879-29204-1371757#=

1960 United States presidential election. Wikipedia.

Retrieved from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1960_United_States_presidential_election