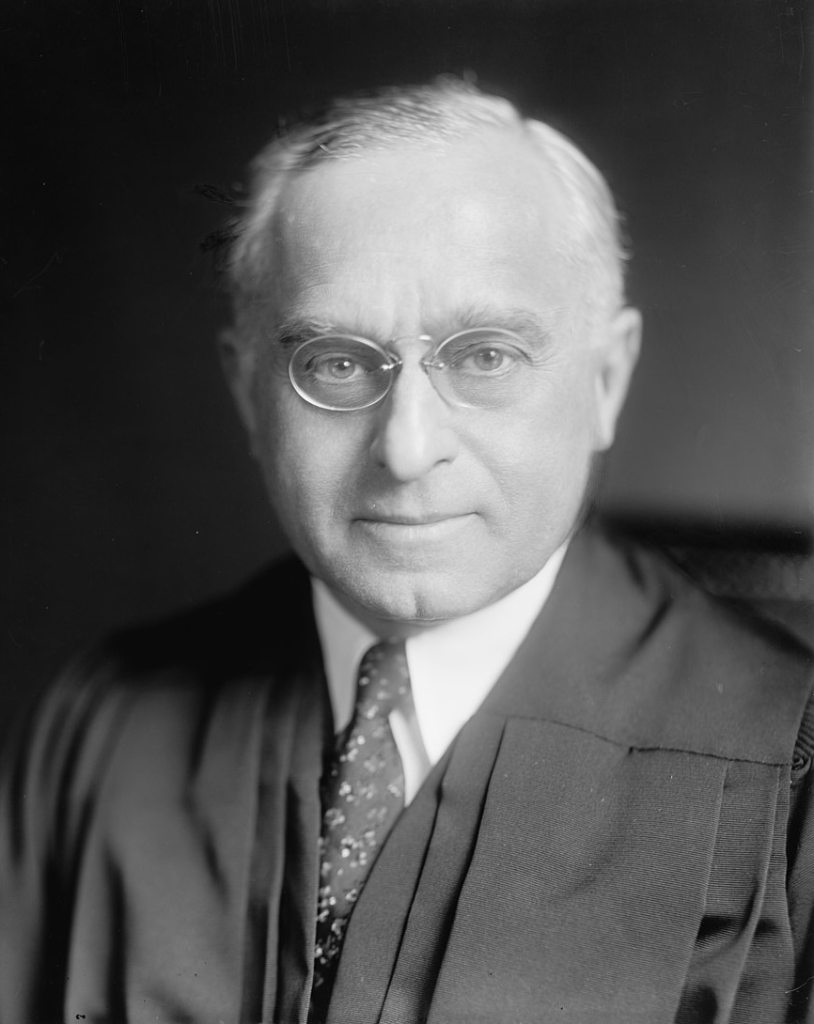

Felix Frankfurter, the author of the Mallory decision.

In 1954, a D.C. home was broken into, and a housewife was choked and raped. This terrible crime became the basis of a major case before the Supreme Court that would cause a political firestorm. The perpetrator was 19-year-old Andrew Mallory, who was convicted of the rape and sentenced to death, and after his arrest he had been interrogated for seven hours before confessing to rape (Time Magazine). There was no evidence of torture or coercion in this confession, but it was also shown that there was a judge available during this time. Mallory appealed his sentence up to the Supreme Court based on the length of his pre-hearing detention. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Mallory v. U.S. in 1957 that any confession obtained after an unreasonable delay was inadmissible in federal court. This meant that arrested persons had to promptly be presented to judges and that testimony produced during an “unnecessary” delay could not be considered by judges, and Mallory was freed.

This decision was met with popular disapproval, especially from conservatives. Senator Strom Thurmond (D-S.C.) issued a statement condemning the ruling, holding that “Any police abuse this decision prevents will be replaced many times over by criminals abusing the laws of the States and Nation under the umbrella of the Supreme Court decision” (Clemson University). Thurmond, a frequent critic of the Warren Court, would also make the Mallory decision an issue during the consideration of Justice Abe Fortas to be elevated to chief justice. However, it wasn’t just strong conservatives who condemned the Mallory decision; Kenneth Keating (R-N.Y.), who was frequently associated with the GOP’s Rockefeller wing, stated, “I cannot believe that the universal rejection of the Mallory (rule) approach in all other jurisdictions (except Federal) is based on a callous unconcern for the rights of the accused. The Mallory decision simply went too far in coddling criminals and gave too little thought to the interests of the public…Brutal or other unlawful police actions should of course be exposed and condemned” (CQ Press). Congress opted for action.

On July 2, 1958, the House passed 294-79 a bill that would make statements obtained from a defendant admissible in court during a period of unreasonable delay, directly overturning the Mallory decision. The votes against mostly came from liberals. Senator Jacob Javits (R-N.Y.), for instance, opposed the bill as he regarded it as “unnecessary” and expressed concern that Congress was making the first move in a “raid” on the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court (CQ Press). However, the bill died in the Senate due to the efforts of liberal Senators John Carroll (D-Colo.) and Wayne Morse (D-Ore.). In 1959, the House again passed an anti-Mallory bill on July 7th, and again the Senate prevented its enactment. The House would undertake periodic efforts to undo the decision and thus make it easier to prosecute criminal defendants. With crime rising substantially in the 1960s, the omnibus crime bill in 1968 was passed that included several provisions that strengthened the criminal code. The act notably altered the Mallory Rule so that a confession could be admitted into evidence if a judge found it was voluntary, and that delay was not unreasonably longer than six hours (Time Magazine). In between Mallory and the 1968 omnibus crime bill, a more famous decision would catch the public eye in Miranda v. Arizona (1967), which instituted the requirement of police reading of a defendant’s rights to them before interrogation.

And what happened to Andrew Mallory? Mallory, it turns out, was a repeat offender. He had numerous jobs he was in and out of and after a babysitting job went sour, he broke into the family home and beat the wife, and in 1960, he broke into another home and beat and raped a mother of four children (Time Magazine). He was convicted of the latter crime and served 11 years in prison. Mallory was shot and killed a year later by a police officer while on the run after attacking and robbing a couple after pointing a gun at another pursuing officer (Time Magazine).

References

Figure in Key Case Before High Court Is Killed by Police. (1972, July 12). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

Mallory Rule. CQ Press.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal58-1341657#_=_

Statement By Senator Strom Thurmond in the Senate with Reference to the Supreme Court Decision in the Mallory Case. (1957, June 27). Clemson University.

Retrieved from

The Law: Andrew Mallory, R.I.P. (1972, July 24). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6840001/the-law-andrew-mallory-r-i-p/