In 1959, longtime Congressman Daniel A. Reed, who had been a staunch opponent of just about everything FDR stood for, including Social Security, died after 40 years in office. This upstate New York district was sure to elect in his place a Republican, and it did in attorney Charles Ellsworth Goodell (1926-1987), who had previously served as a liaison assistant for Congress to the Department of Justice. However, Goodell would prove a much more flexible politician than Reed ever was.

Support for Eisenhower and Beyond

Goodell’s political views seemed to represent well those of his constituency based in upstate New York, being conservative on domestic issues and an internationalist on foreign policy. During the Eisenhower Administration, he backed his vetoes on spending bills, opposed food stamps, opposed federal aid to economically depressed areas, and opposed federal aid for school construction. He also supported the federal anti-preemption bill, contrary to President Eisenhower’s position, which would strengthen the ability of states to crack down on subversion, which had been weakened by a Supreme Court ruling. Goodell was no squish during this time. He did, however, support foreign aid, contrary to his predecessor, Reed, who true to his non-interventionist past consistently opposed Mutual Security bills.

Goodell vs. JFK

During the Kennedy Administration, Goodell opposed expanding the House Rules Committee, federal aid to school construction, strong minimum wage legislation, and accelerated public works projects. He was, however, supportive of educational television.

Crafting a Compromise on Equal Pay

One of Goodell’s legacies came in the form of none other than the Equal Pay Act. The Kennedy Administration initially came up with a sweeping equal pay law for women with a whole new bureaucratic structure to be created. Major business interests as well as many conservatives were opposed to Kennedy’s proposal. Paul Findley (R-Ill.), at this point in the arch-conservative phase of his career, held that the bill would “do more harm than good” and that it would “cut back on female employment” (CQ Almanac). Goodell, however, managed to craft substitute legislation that instead of making it a separate law simply added equal pay to the Fair Labor Standards Act, thus not requiring a new bureaucracy and it being administered through a federal agency that American business had over twenty years of experience with (CQ Almanac). That became the law we know of today that got consensus support. He was also a supporter of civil rights legislation overall, voting for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and fair housing. Even his one vote against a significant civil rights measure, the 24th Amendment, was on the grounds that he thought a legislative poll tax was constitutionally permissible and should be adopted in that form.

Goodell vs. LBJ

Goodell’s record during the Johnson Administration was moderately conservative. In 1964, he voted against the Economic Opportunity Act, federal funds for mass transit, and against food stamp legislation. The following year he voted against the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and the creation of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. However, Goodell did support final passage of the Social Security Amendments, which included Medicare, as well as the Appalachian Regional Development Act. Despite usually opposing the prevailing Democratic rule in the 1960s, Goodell was a constructive legislator.

Crafting Substitutes to the Great Society and Ascending to the Senate

In 1964, Republicans took it on the chin with the candidate at the top of the ticket, Barry Goldwater, harming many down ticket. After the 1964 election loss, Goodell was among the young members of Congress who led the successful push to oust Minority Leader Charles Halleck (R-Ind.) for Gerald Ford (R-Mich.), and he had been instrumental in getting Ford the post of chairman of the Republican Conference two years before over its incumbent, Charles B. Hoeven of Iowa (Barnes). While an opponent of Great Society legislation, he not merely opposed but also sought alternatives. One such effort was the “Opportunity Crusade” proposal of the House GOP leadership as a substitute for the “War on Poverty”. Goodell was an effective critic of the Office of Economic Opportunity. He referred to the OEO as “the fuddle factory” and pledged that the “Opportunity Crusade” would “eliminate the waste and scandal and abuses” (McLay, 6). However, it wasn’t all smooth sailing on ideas. As Donald Rumsfeld humorously reflected, “We would put forth what were called Constructive Republican Alternative Proposals. If you think of the acronym, it was a problem” (Curtis). Nonetheless, Goodell was one of the standout legislators among the Republicans for his efforts, and was held in high esteem by Minority Leader Ford. Richard Reeves of The New York Times characterized him as “kind of the Paul Ryan of his time” (Curtis). Death once again benefited Goodell’s political career after Sirhan Sirhan assassinated Robert F. Kennedy. Governor Nelson Rockefeller appointed Goodell to the Senate, and he resigned the House on September 9th to serve. His time in the Senate would prove much different from his time in the House.

Goodell vs. Nixon

The Goodell of the Senate was not the Goodell of the House. For one thing, House Goodell represented an upstate New York constituency, while Senate Goodell represented the entire state, thus significantly different political considerations existed. What’s more, he is keen on staying in the Senate, and one way to go about doing this is to win primaries in multiple parties. In New York at the time, there were four parties whose primaries mattered: Democratic, Republican, Liberal, and Conservative. Goodell hoped to win not just the Republican nomination but the Liberal nomination as well. The Liberal Party, a uniquely New York party, had been founded in 1945 as an independent alternative for liberal-minded voters who were turned off by the machine politics of the Democrats. While often the Liberal Party would nominate Democrats, they could sometimes nominate Republicans too. Republican Senator Jacob Javits, for instance, was repeatedly nominated by the Liberal Party, and the Liberal Party’s nomination of New York City Mayor John Lindsay for another term in 1968 saved his political career for four years.

The change in Goodell was soon noticed in Washington, as it was one of the most pronounced that the place had ever seen. He had gone from opposing much of the Great Society to voting to uphold and expand it. Some domestic liberal votes he cast included for national unemployment compensation standards, increased funds for food stamps, increased funds for higher education, and urban renewal. On crime, he opposed “no knock” warrants for drug offenses. Conservative James Buckley, brother of National Review founder and editor-in-chief William F. Buckley Jr. quipped, “It was the most stunning conversion since Saint Paul took the road to Damascus” (Curtis). For the Congressional basketball game, Congressman Mo Udall (D-Ariz.), noted for his sense of humor, came up with a new term for a play. It was called the Goodell Shift, in which when all players were on the right side of the court, someone would yell, “Senate!” and a player would move left (Curtis). Goodell’s liberalism also crossed Nixon something fierce.

Not only did Goodell vote against both Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell for the Supreme Court, he also opposed Nixon on Vietnam. Goodell’s stance on Vietnam at least appeared to be genuine. In 1968, he wrote to Congressman Al Quie (R-Minn.) that “We should not be engaged in a land war 10,000 miles away” (Curtis). Goodell voted for both the Cooper-Church Amendment prohibiting funds for American troops in Cambodia in 1970, and the McGovern-Hatfield Amendment the same year, providing for a six-month timetable for withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam. He also did some things off of the Congressional Record that aligned him with the left, such as marching with Coretta Scott King in a Vietnam War protest, publicizing the Pentagon Papers, and hosting Jane Fonda at his office (Curtis). His anti-Vietnam War position even got him endorsed by none other than Noam Chomsky. Nixon, who was once on good terms with Goodell and had previously assessed him as “our egghead in Congress – a creative intellectual in the best sense of the word”, was now dead set against him remaining in the Senate (Barnes). Goodell’s campaign slogan in 1970 was “too good to lose!” While looked upon negatively by Nixon and his administration, he was regarded favorably by the Ripon Society, a liberal Republican group, for being “blunt and outspoken against the war, and against mediocre Supreme Court Justices, and against useless toys for the military like the ABM…” (Ripon Forum, 13). The Nixon Administration decided upon a response to Goodell to secure him a permanent vacation from the Senate.

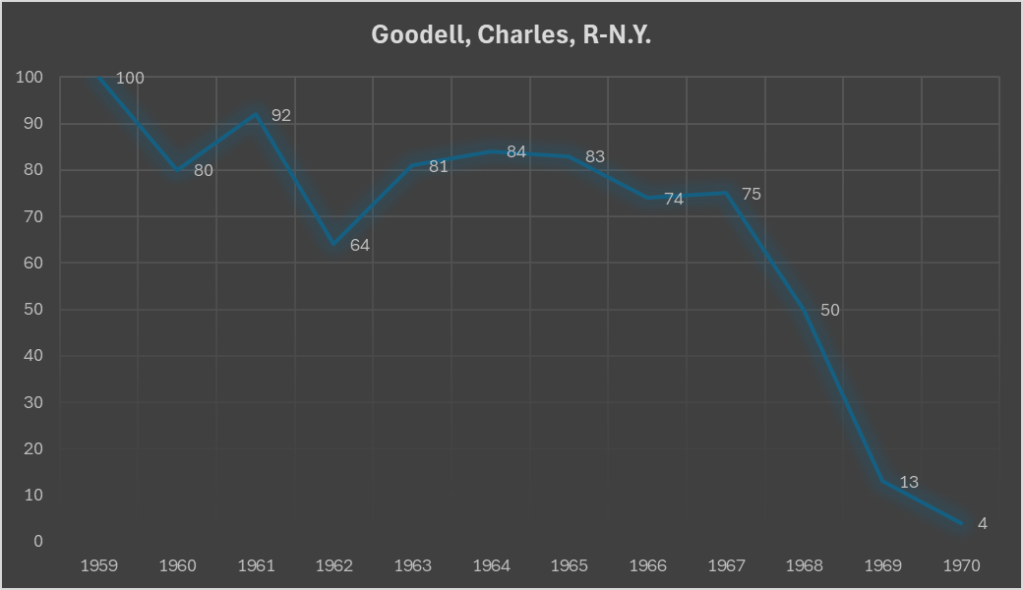

Nixon’s tool to defeat Goodell was his attack dog, Vice President Spiro Agnew. He was to publicly condemn Goodell on multiple occasions, and this would elevate his profile among liberals, thus resulting in a split in the liberal vote between him and Congressman Richard Ottinger. Agnew condemned what he called his “radiclib ideology” (Barnes). However, this would not be the most notable attack. The real kicker, and one that was considered deeply shocking in its day, was when he said, “If you look at the statements Mr. Goodell made during his time in the House and compare them with some of the statements I have been referring to, you will find that he is truly the Christine Jorgensen of the Republican Party” (Curtis). For context, Jorgensen was a famous transsexual of the time. Although Goodell’s strategy to win the Republican and Liberal nominations worked, and as a bonus he secured the endorsement of The New York Times, Nixon’s strategy was working too. Ottinger sought the liberal vote as well and came out against Goodell’s House record, stating that “As a member of the House of Representatives he was one of its most reactionary members. He just voted against everything constructive” (Curtis). Ultimately, the liberal vote split, with the Conservative Party’s candidate, James Buckley, who got the unofficial support of the Nixon Administration, winning the election. This was quite a turnaround for a man who only two years before had only netted 17% of the vote in running for the Senate. Embarrassingly for a man who ran on the slogan of “Too good to lose”, he came in third, as polling had predicted over a week earlier (The Observer). By the criterion set by the conservative interest group Americans for Constitutional Action (ACA), while in the House he had either paired or voted with them on 139 out of 179 votes, but in the Senate, it was only 3 out of 39 votes. Overall, he sided with ACA positions 65% of the time. Goodell’s DW-Nominate score stands at a 0.253, which accounts for both his House and Senate service and indicates moderate conservatism. Just as an illustration of the dramatic change, here is a line graph of his adjusted ACA scores throughout his whole legislative career:

Although Goodell would never again run for public office, he still had a friend in Gerald Ford. Once Ford became president after Nixon’s resignation, Goodell became one of his close advisers. Goodell commented happily on this development, “For me, it’s a new day, a new world. The sun has come out again” (Tolchen). Goodell’s influence may have had a hand in motivating Ford to select Nelson Rockefeller as his vice president. However, he denied directly recommending him, stating, “I said good things about Nelson Rockefeller, but I didn’t recommend anybody personally” (Tolchen). Ford would appoint him chairman of the Presidential Clemency Board, which reviewed and decided on clemency applications by Vietnam War draft dodgers and deserters. In his post-Senate career, he specialized in representing foreign business interests trying to expand into the United States. On January 16, 1987, Goodell suffered a massive heart attack and died at George Washington University Hospital five days later, aged 60. His son, Roger Goodell, is the current commissioner of the NFL.

References

Barnes, B. (1987, January 22). Charles E. Goodell, Ex-Senator from New York, Dies at 60. The Washington Post.

Retrieved from

Curtis, B. (2013, February 4). Mr. Goodell Goes to Washington. Grantland.

Retrieved from

https://grantland.com/features/roger-goodell-father-senator-charles-goodell/

Equal Pay Act for Women Enacted. CQ Almanac 1963.

Retrieved from

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal63-1315824

Goodell, Charles Ellsworth. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/3670/charles-ellsworth-goodell

Goodell holds firm on Senate bid; battles against Agnew and polls. (1970, October 26). The Observer (Notre Dame and St. Mary’s College newspaper).

Retrieved from

McLay, M. (2019). A high-wire crusade: Republicans and the War on Poverty, 1966. Journal of Policy History, 31(3), pp. 382-405.

Retrieved from

New York: Charles Goodell, outcast and underdog, fights Agnew and the Conservatives. (1970, November). Ripon Forum, 6(11).

Retrieved from

https://riponsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/1970-11_Vol-VI_No-11.pdf

Tolchen, M. (1974, September 12). Goodell, Once a Forgotten Man, Is Now a Close Adviser to Ford. The New York Times.

Retrieved from