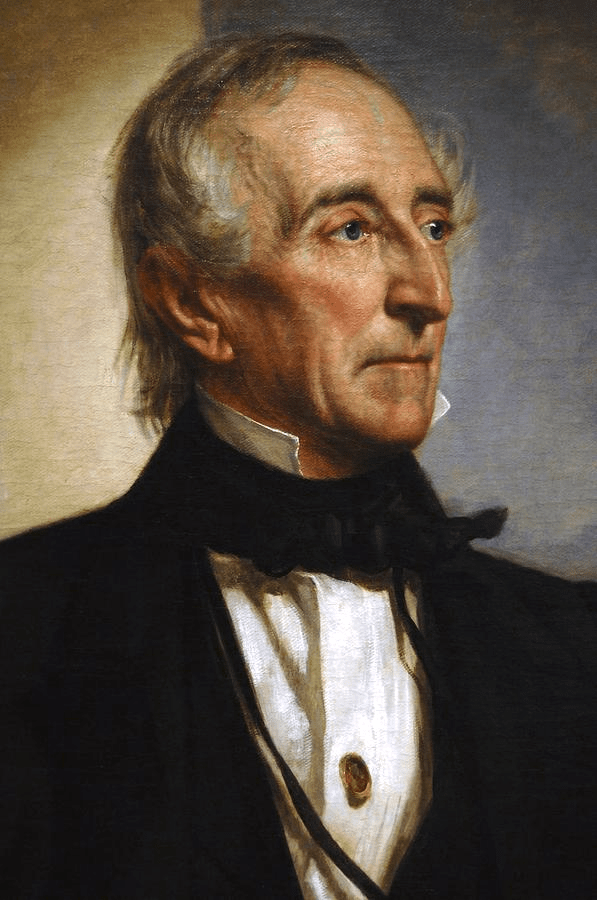

John Tyler

John Tyler is one of America’s forgotten presidents, a group I have covered before. If remembered, he is remembered as the Tyler in “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” in the 1840 presidential campaign, as the “accidental president” after President Harrison’s death, as well as for being the only former president to join the Confederacy. Also significant about him was his veto of his own party’s effort to reconstitute the Second Bank of the United States, something the Whig Party should have anticipated about him given his support for Jackson’s veto of renewing the charter of the Second Bank as a senator. However, there was a tremendous event, not remembered much today, that occurred during Tyler’s presidency that was a near miss for him but killed six people, including several members of his administration.

Captain Robert F. Stockton

February 28, 1844, was supposed to be a day of celebration, and indeed for a time it was, for it was a cruise on the USS Princeton, a massive warship that had two massive guns on it, the Oregon and the Peacemaker. In attendance included President Tyler, several members of his cabinet, Colonel David Gardiner and his daughter Julia, and Dolley Madison among many others. This vessel and its weaponry were proudly designed by its Captain Robert F. Stockton and the Swedish inventor John Ericsson, the latter who was not present on this day. Unknown to the guests on board was that Captain Stockton and Ericsson previously had argued over whether the Peacemaker was safe to fire (Baycora). The Peacemaker, unlike the Oregon, had not been tested. Furthermore, at the time, the Peacemaker was the largest naval cannon in the world at over 27,000 pounds (Baycora, Blackman). With the first shot fired that day, all was well, with the Peacemaker impressing onlookers with its mighty boom. The second shot also was a crowd pleaser, and the band played “Hail to the Chief” as the ship passed Mount Vernon (Blackman). It looked like perhaps Ericcson’s concerns had been overwrought. At roughly 3 PM most of the women went below deck for a fancy lunch, and Secretary of State Abel Upshur joked upon accidentally picking up an empty bottle of champagne for toasting the president, that the “dead bodies” must be cleared away before he could start, with Captain Stockton while handing Upshur a full bottle adding “There are plenty of living bodies to replace the dead ones” (Blackman).

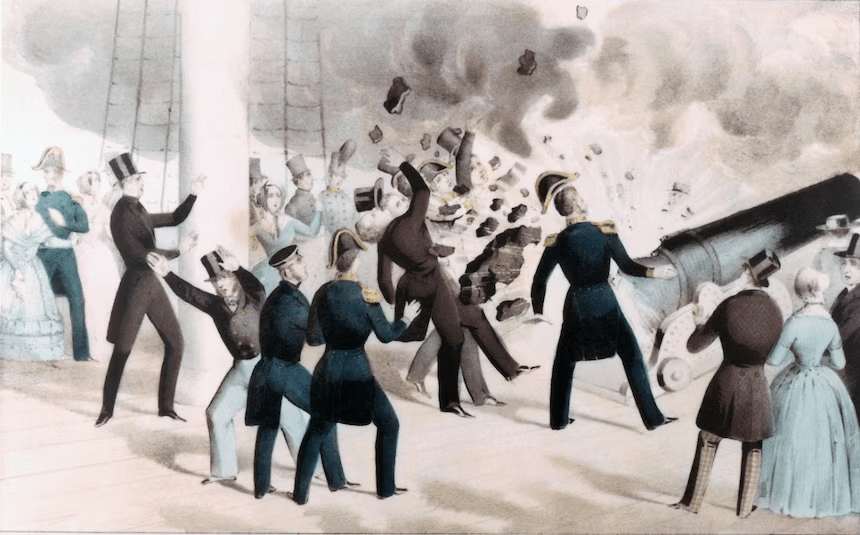

Initially, the cannon was only to be fired twice, but word got to Stockton that a guest had asked for a third firing to honor George Washington. This guest turned out to be Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer, and Stockton interpreted this as an order, so he proceeded (Blackman). Although urged to go outside to witness the third firing, Tyler delayed descending up to the deck. This decision may have saved his life. When Stockton fired a third time as Tyler was halfway up, the left side of the cannon exploded, propelling fiery iron and shrapnel.

An illustration of the Peacemaker disaster published shortly after.

Six people were killed, among them Upshur and Gilmer, as well as Beverly Kinnon, construction chief of the navy, American envoy to Belgium Virgil Maxcy, Colonel David Gardiner, and Tyler’s enslaved valet, Armistead. It was a grisly scene: Upshur had his arms and legs broken and his bowels torn out, Gilmer was decapitated by metal from the gun, Maxcy’s arm flew off and hit a lady on the head, Colonel Gardner’s arms and legs were blown off, and Armistead died ten minutes after being hit by a piece of the gun (Blackman). Many more were injured. This included Captain Stockton, who suffered severe facial powder burns and was inconsolable at the gruesome scene before him, and Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who was knocked down and suffered a concussion (Blackman). Dolley Madison, at the time 76, did her best to assist the wounded and the traumatized. Despite her composure in the face of tragedy, the event deeply impacted her. As her niece recalled, “She came in quietly, with her usual grace, spoke scarcely a word – smiled benignly – but those who knew her perceived her faltering voice and inability to stand without support. Of the horrible scene she dared not trust herself to speak, nor did she ever hear it referred to without a shudder” (Baycora). Gardiner’s daughter, Julia, who President Tyler had been seeing, fainted on hearing of her father’s death. President Tyler, who himself had wept at the sight of Upshur and Gilmer, carried her off the ship.

Julia Gardiner Tyler, who was 30 years younger than her husband!

Although Gardiner had been hesitant about marrying the much older Tyler, in the aftermath of this traumatic event she found she could be interested in no other man. As she wrote, “After I lost my father, I felt differently toward the president. He seemed to fill the place and to be more agreeable in every way than any younger man ever was or could be” (Thomas). Tyler and Gardiner married only months later. President Tyler in his writings explicitly blamed no one for this event, and Stockton would later briefly represent New Jersey in the Senate. However, one man may have blamed himself. Commodore William M. Crane, who supervised the construction of the USS Princeton and had disapproved of the Peacemaker, slit his own throat in his office on March 18, 1846, with his family attributing his brooding over the disaster as a cause (Prabook).

References

Baycora, F. (2021, March 4). The USS Princeton and the Disaster You’ve Never Heard Of. Historic America.

Retrieved from

The USS Princeton and the Disaster You’ve Never Heard Of — Historic America

Blackman, A. (2005, October). Fatal Cruise of the Princeton. Naval History, 19(5).

Retrieved from

Fatal Cruise of the Princeton | Naval History Magazine – October 2005 Volume 19, Number 5 (usni.org)

Carrigan, C. (2023, February 24). A “Terrible Catastrophe”: The February 1844 Naval Gun Explosion that Almost Killed a President. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Retrieved from

Thomas, H. (2024, February 13). How Tragedy Led to Love for John Tyler and Julia Gardiner. Library of Congress.

Retrieved from

William Montgomery Crane. Prabook.

Retrieved from