Now that Penrose was in the Senate, he was on the same national footing as Matthew Quay. However, soon his influence in that chamber would surpass Quay’s, for he was in legal trouble. Penrose had not liked Quay’s methods for their jail risk, and Quay was indicted in 1898 for allegedly defrauding the People’s Bank in Philadelphia. Although the evidence in this case was weak and he was ultimately acquitted, this incident resulted in him narrowly being denied seating to the Senate the following year, and for a brief time Penrose was the state’s only senator. Although Quay managed to get back in and remained boss, Penrose was considerably more of a policy man. The former pretty much worked on whatever he saw as benefiting Pennsylvania, but the latter got on the Senate Finance Committee and would twice serve as its chairman. In 1903, Quay was starting to die from chronic gastritis and upon his death the following year, Penrose was the undisputed leader of the machine.

Robert Bowden (1937) wrote that there were four great consistencies about Penrose, which informed how he carried out his life and career: “1. His first, last, and only love was politics…2. He had an unshakeable obsession of greatness…3. He was boldly, consistently, beautifully, free from hypocrisy”…4. He had no scruples or “set” principles to live up to or avoid” (44, 45, 46). However, this isn’t quite true. Bowden (1937) does note earlier in his book that “He had no scruples against anything – except stupidity” (11). Furthermore, Penrose was far more conservative than his predecessor bosses. Prior bosses Simon Cameron, J. Donald Cameron, and Matthew Quay had DW-Nominate scores of 0.275, 0.214, and 0.171. This indicates that these men were moderately ideological, and for Quay its possible that that’s just how the cookie crumbled on his votes that were geared towards his power and Pennsylvania. Penrose’s DW-Nominate score was a 0.619 by contrast. As leader of the Pennsylvania GOP, he figured why engage in petty corrupt practices such as graft and accepting bribes when you can legally solicit contributions from corporate interests…after all conservative Republican policy is geared towards benefiting the expansion of commerce and by extension growing well-paying jobs. Why shouldn’t the businessmen pay for it? As Robert Bowden (1937) writes, “He was always very scornful of Quay and his sort for profiting by the petty graft in contracts and the like. Franchises, contracts, gambling with State funds, small bribes, and things of that kind, furnished the source of Quay’s wealth. But why risk going to the penitentiary by picking up little amounts of graft when the real money was to be had by working for those who controlled mines and steel mills and railroads. They paid handsomely for a law passed or defeated now and then” (188). Penrose went a bit further in his practices than mere solicitation of campaign funds, however, as he pioneered “squeeze bills”. He would have an ally in the Pennsylvania legislature introduce legislation to regulate a particular industry, and once a sufficient level of campaign contributions came in, he promised to have the bill shelved, and it was (Beers, 53). This turns the traditional thought of campaign contributions on its head; the popular conception of big business is that they push politicians to act for them through campaign contributions, but Penrose pushed big business for contributions in a way far greater than mere calls and meetings. Speaking of calls, Penrose was the master of phone calls. Rather than any communication on critical issues being written down, he used the telephone so if any dispute came up over what was said, he could always deny it.

Penrose’s foremost political cause was raising tariffs. When one of his men asking what the issue of the upcoming campaign was going to be, he responded, “Hell, man! Have you arrived at the age of discretion and don’t know that there’s always only one question worth making an issue out of? Protection! Protect the great industries of this State and you start dollars flowing out to every home in the State. We make that possible because we control the government at Harrisburg and at Washington. We intend to keep that control” (Bowden, 19). Indeed, high tariffs were the bread and butter of the traditional GOP, as much so as income tax reduction in modern times. What’s more, it tended to be the progressives among the Republicans who were most likely to dissent on tariff questions. However, Penrose’s political ideology was a bit greater than tariffs. Indeed, per Bowden (1937) with some exaggeration states, “His sole interest in public life was centered on keeping business free from governmental regulation” (250). He was also opposed to most reform causes of his day, opposing amendments to the Constitution for direct election of senators, women’s suffrage, and Prohibition. The latter distinctly offended his philosophy that he should do whatever he wanted and that others ought to be free to do so if they had the guts. Senators whose counsel he valued (including DW-Nominate scores) included per Robert Bowden (1937), “John W. Weeks [0.587], Massachusetts; Warren Harding [0.595], Ohio; Frank Brandegee [0.778], Connecticut; Henry Cabot Lodge [0.568] and W. Murray Crane [0.669], Massachusetts; Reed Smoot [0.514], Utah; Lawrence Y. Sherman [0.807], Illinois; James W. Watson [0.55], Indiana; Charles Curtis [0.433], Kansas; James Wadsworth [0.434], New York; William P. Dillingham [0.602], Vermont; Miles Poindexter [0.199], Washington; Jacob H. Gallinger, [New Hampshire] [0.553]. A noble band, these and not a progressive heresy in a carload” (244). With the sole exception of Poindexter (the author was probably referring to his last four years in the Senate, in which he had a major conservative shift), all of these men were indeed bona fide conservatives.

Penrose held a strong dislike for stupidity and hypocrisy and thought quite ill of reformers. His attitude could be summed up thusly, “He was quite sure that every reformer was a hypocrit[e] or an ignoramus and not worth worrying about, and that most reformers attack conditions about which they know nothing. Besides, it didn’t cost them anything to attack other people’s property or habits” (Bowden, 235). Penrose would also not have trucked to today’s activists on left-wing subjects. Per Robert Bowden (1937), “He had no sympathy for reform and despised reformers. To him anybody who whined of injustice and immoral conditions was a weakling who, being both cowardly and weak, tried to get other weaklings like himself to abolish that which he was afraid to have for his very own” (32). For his personal attitudes towards women, they were unknown aside from his enjoyment of ladies of the night. Speaking of personal matters…

The Peculiarities of Penrose

Despite Penrose being a germaphobe, being hesitant to shake hands and despised people whispering in his ear, his hands were often dirty and his nails unkempt. Historian John Lukacs (1978) described him as “gargantuan, gross, and cynical”. His gargantuan size was due to his insane levels of eating: at his peak weight he was over 300 pounds. On one evening at dinner, Penrose reportedly ate “a dozen raw oysters, chicken gumbo, a terrapin stew, two canvas back ducks, mashed potatoes, lima beans, macaroni, asparagus, cole slaw and stewed corn, one hot mince pie, and a quart of coffee. All of which he stowed away while he drank a bottle of sauterne, a quart of champagne, and several cognacs” (Time Magazine). Such a meal, although it sounds incredible, was not unusual for him and other waiters from other establishments had similar Penrose stories. On another occasion, by this time in his early 50s, he dined with Congressman J. Washington Logue, who reported that he drank nine cocktails and five highballs and after ate 26 reed birds followed by the wild rice they were served atop and then drank a bowl of gravy (Bowden, 191-192). On yet another occasion, Penrose and another man competed for $1000 bet on who could eat more. The victor was Penrose who ate fifty iced oysters and consumed a quart of bourbon, and the loser was hospitalized, with Penrose remarking to his astounded audience, “I’ve probably made a damned hog of myself” (Noel & Norman, 11-12).

Penrose was not known to be ashamed of anything about himself. When entertaining guests on his yacht, he appeared on deck ready for a swim, to which a lady screamed, with Penrose responding, “Madame, I grant that mine is not the form of Apollo, but it is too late for either of us to do anything about that. But if I present what to you are strange or unfamiliar phenomena, it is you who should be ashamed, not I” (Time Magazine). He did, however, in his later years have a screen put up for when he was dining at restaurants.

The 1912 Election: Penrose Sides with the Establishment

In 1912, Penrose backed William Howard Taft over Theodore Roosevelt as Roosevelt was an outright threat to bosses like him, but Roosevelt won the state. Penrose had beforehand reached the sober realization that the public was tired of the GOP and were in a reformist mood, thus the battle was not for the presidency, rather control of the party, and he ultimately won that battle. The election did come at a cost to Penrose as he temporarily lost his post as a national committeeman but got it back in 1914.

Penrose and Wilson

Penrose was not a fan of President Wilson, who he derided as a “schoolmarm” (Lukacs). Although he managed to add the oil depletion allowance to the 1913 Revenue Act, he voted against the bill for its tariff reductions. Penrose would be one of the most staunchly opposed Republicans to Wilson’s “New Freedom” agenda and was strongly for military preparedness. Penrose during World War I predicted the introduction of the Versailles Treaty and the 1920 election: “Hell! Just encourage [the Democrats] a bit and they’ll not only lick the Kaiser but themselves as well – with a little help from us. You see, it’s like this. Woodrow got us into this war to make the world safe for Democracy. We’re a big brother now, not to one nation but to a dozen. They’ll borrow all we’ve got. Be damned lucky to keep our shirts. Then Woodrow will insist on making a peace treaty that’ll sound like a high school oration. Just about that time the pious taxpayer will get tired of being up in the clouds and they’ll call in us good Republicans to get them back to earth…Yes, sir, idealism is a great thing, but it costs too much” (Bowden, 246).

The 1914 Election: Penrose Faces the People

Boies Penrose had opposed the 17th Amendment for direct election of senators, but he was outvoted and progressive reformers hoped that Penrose and men like him would be turned out of office. Indeed, his eccentricities made it possible that this would be so. However, Penrose remained highly intelligent, and he visited cities and towns and gladhanded the voters to gain support. His opponents also had a problem in that they were divided: former President Theodore Roosevelt endorsed Progressive Gifford Pinchot and President Woodrow Wilson endorsed Democrat A. Mitchell Palmer. They split the opposition vote, and Penrose came out ahead with 46.76% of the vote. After a triumphant reelection in 1920, he said to a reformer friend of his, “Give me the People, every time! Look at me! No legislature would ever have dared to elect me in the Senate, not even at Harrisburg. But the People, the dear People, elected me by a bigger majority than my opponent’s total vote by half a million. You and your ‘reformer’ friends thought direct election would turn men like me out of the Senate! Give me the People, every time!” (Kennedy) Although Penrose certainly had a new-found appreciation for the people, he remained a cynic. He said of the voting public, “The people are all right, but their tastes are simple: they dearly love hokum” (Bowden, 198).

Penrose Saves La Follette and Helps Bring Down the Versailles Treaty

In 1917, Senator Robert La Follette (R-Wis.), a noted progressive, had voted against declaring war on Germany. This, in addition to distorted reports of a speech he gave that falsely alleged that he had defended the sinking of the Lusitania, had many of his fellow senators wanting his immediate expulsion from politics. However, when the vote was coming up with La Follette appearing before the Senate afraid, “Big Grizzly” approached him, put his big arm around him, and escorted him to his seat. Penrose publicly opposed La Follette being ousted for his stance on the war, and with most Republicans voting with Penrose, La Follette was not expelled. Like La Follette, Penrose was a strong opponent of the Versailles Treaty, but unlike him, he was not considered an “irreconcilable”, or one who refused to vote for the treaty under any circumstances.

Decline and Deciding on a President

In the 1910s, Penrose began to face a considerable challenge from within the Pennsylvania GOP: the Vare brothers. The Vare brothers (William and Edwin) of Philadelphia were notorious contractor bosses, and William even made arrangements with mobsters Lucky Luciano and Waxey Gordon in which any operation of theirs would be subject to his veto. Once Penrose and Edwin Vare passed, William would be the undisputed boss in Philadelphia Republican politics. While alive, Penrose had to contend with their growing influence in the city, where his influence was the weakest. Worse yet, his health was failing as he was getting into his late fifties given his indulgent consumption of oysters, steaks, and other culinary delights. As Robert Bowden (1937) wrote, “He no longer had an intellectual curiosity to satisfy; even that dulled on him. Having nothing else to occupy him he turned all his thoughts to the gratification of his many appetites. But already he had pampered them too much and they rebelled on him. His stomach no longer would accept, without loud complaint, five-pound steaks. His capacity for liquor had dwindled shamefully. Hemorrhoids caused him no little worry and inconvenience. About everything physical was wrong with him. He was now only a man-mountain of three hundred pounds of diseased flesh” (255). Despite his decline, he remained as active on the political scene as he could.

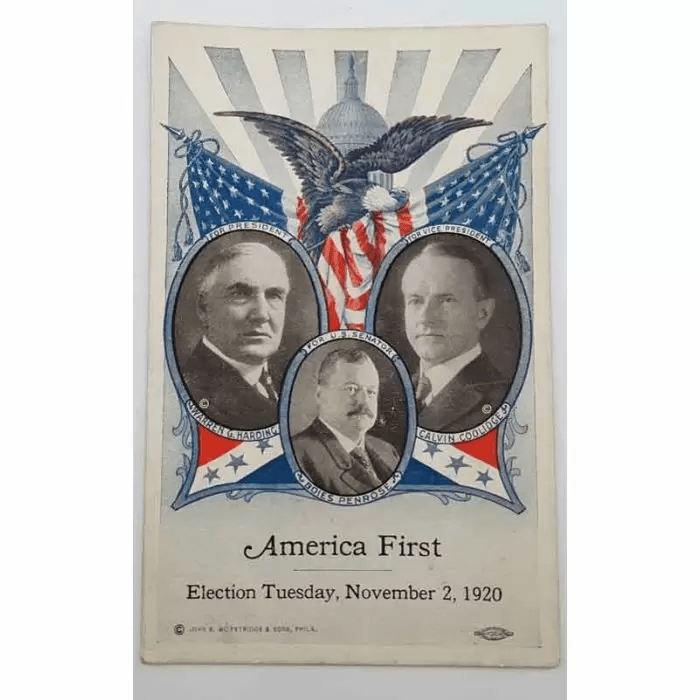

In 1919, a group of journalists asked Penrose who the ideal Republican candidate for president would be, and he responded: “We shall select a man with lofty ideals. He shall be a man familiar with world problems. He will be a man who will appeal warmly to the young voter – the young men and women of our country. A man of spotless character, of course…A man whose life shall be an inspiration to all of us, to whom we may look as our national hero…The man I have in mind is the late Buffalo Bill” (Lukacs). The man Penrose actually looked to for the presidency was Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio and asked him about it. He saw in Harding a compatriot in his conservatism, and was one of the most important figures backing Harding’s nomination, and although he could not attend the Republican National Convention due to poor health, he was quite active in the proceedings and ran up a telephone bill of $7000 (not accounting for inflation!) in July 1920. He recommended to Harding Pennsylvanian industrialist Andrew Mellon as Treasury secretary, and sponsored the Emergency Tariff Act in 1921 (although he initially opposed it) as well as the Revenue Act of 1921 (income tax reduction). His accomplishments in 1921 were the last of his career. Penrose had been diagnosed with terminal cancer and on December 31, 1921, he died in his bed. Despite rumors that Penrose had millions secretly stashed away, he personally had not profited from politics. He was born rich and died a considerably poorer man, as his brothers were not left with much on his death.

To be completely honest, I kind of like Boies Penrose. His stands against stupidity and hypocrisy resonate with me, as do his efforts to make the machine less in contradiction with the law. Does this make me a cynic? I hope not, for it is not a way to live. Although Penrose really took things to extremes. I’d call him a Diogenes, but he had too much enjoyment of excess and the high life for that.

References

65th Congress – Senators. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/congress/senate/65/text

Books: Boies Would Be Boies. (1931, November 23). Time Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://time.com/archive/6748250/books-boies-would-be-boies/

Beers, P.B. (1980). Pennsylvania politics today and yesterday: the terrible accommodation. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Bowden, R.D. (1937). Boies Penrose: symbol of an era. New York, NY: Greenberg.

Cameron, James Donald. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/1435/james-donald-cameron

Cameron, Simon. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/1437/simon-cameron

Crane, Winthrop Murray. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/2147/winthrop-murray-crane

Kennedy, J.F. (1956, February 21). Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy at the New York Herald Tribune Luncheon, New York, New York. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Retrieved from

https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/other-resources/john-f-kennedy-speeches/new-york-ny-herald-tribune-luncheon-19560221

Lukacs, J. (1978). Big Grizzly. American Heritage, 29(6).

Retrieved from

https://www.americanheritage.com/big-grizzly

Noel, T. & Norman, C. (2002). A Pike’s Peak Partnership: The Penroses and the Tutts. University Press of Colorado.

Retrieved from

https://www.upcolorado.com/excerpts/9780870816895.pdf

Penrose, Boies. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/7332/boies-penrose

Quay, Matthew Stanley. Voteview.

Retrieved from