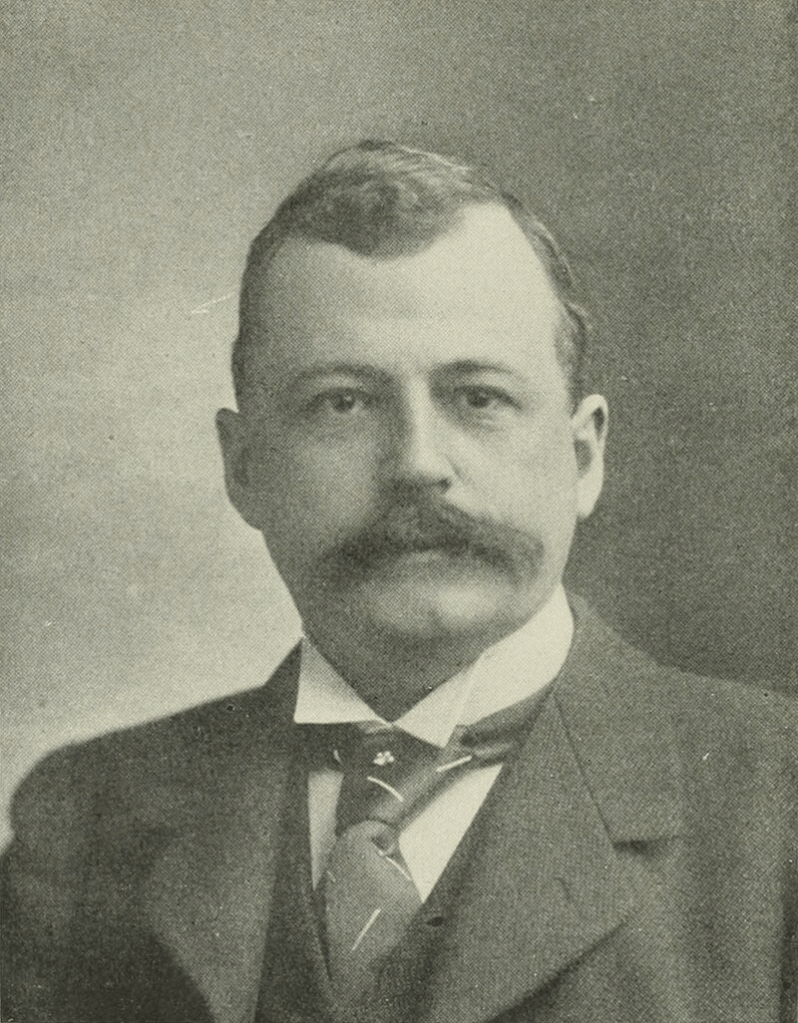

In present day, Pennsylvania is a swing state, although both of its senators are Democrats, and the governor is one as well. The state used to be much different, being a stronghold for the GOP. This domination began with boss Simon Cameron, who had once been a Jackson-supporting Democrat. Although perhaps not the most powerful of Pennsylvania’s Republican bosses ever, Boies Penrose (1860-1921) was the biggest one physically and also the most conservative one. He was perhaps the most unique character of all of them.

An Aristocratic Upbringing and Entering Politics

The Penrose name was quite prominent and the family wealthy, and it was instilled into him from an early age that he was of the elite and a person to be deferred to. While in college, he was 6’4″ and 200 pounds, making for a striking figure, although he would balloon over the years, making his allies and enemies alike refer to him as “Big Grizzly”. Although a prime candidate for football, he would not play, as the thought of coming into physical contact with sweaty men was repulsive (Noel & Norman, 11). Although initially a lazy student at risk of failing, after intervention from his father he righted the ship and graduated with flying colors, developing an intense interest in politics that lasted his entire life and even writing an extensive and masterful paper on Philadelphia’s government. Penrose also wrote on Martin Van Buren, regarding him as “the first and the greatest of American politicians; of that class of statesmen who owe their success not so much to their opinions or characters, as to their skill in managing the machinery of party…He marks the transition in American politics from statesmen like Adams and Webster to the great political bosses and managers of today…Adams was the last statesman of the old school who was to occupy the White House, Van Buren was the first politician president” (Lukacs). Penrose would see Van Buren as a model to emulate, regarding his approach as the acceptance of political reality. He would also identify a core failure of Marxist assumptions, that being that the working classes were not a revolutionary group, rather among the staunchest defenders of property and fundamentally conservative (Lukacs). This seems to ring truer today than even in his day. He carried an ego that was as big as he became, and this led him to instead of associating a lot with his peers, associate with commoners. Instead of going to high-end establishments with peers, he went to pubs and oyster and steakhouses for common citizens, and they would seek out the young intellectual’s wisdom while he would meet the leaders of local political gangs and get connected in the political world (Bowden, 20-21). In this sense, he followed the footsteps of his grandfather, Charles, who had played a critical role in getting the notorious Simon Cameron elected to the Senate in 1857. Like Charles, Boies would crave power. However, he would not crave money unlike most machine bosses…he was already rich. Furthermore, Penrose was keen to avoid risking the penitentiary in the pursuit of political power (Lukacs).

Although he had earned a law degree and worked in a legal firm, Penrose came to have a low opinion of many of his clients. He recalled of his days in law, “My offices were always full. On one side of the waiting room the politicians gathered. Across the other side were my clients. After a few months I decided to choose between them and I chose the least stupid and the most honest” (Lukacs). From then on, Penrose’s full-time profession was politics. He started in opposition to the “Gas Ring” of Philadelphia, and in February 1884 he was able to see to it that no voter fraud occurred on behalf of the ring given his intimidating presence and that he held a list of registered voters in his hand, making sure the vote came in right; the machine’s candidate lost 3 to 1 (Lukacs). In November, he was elected to the state legislature. Upon going to Harrisburg, Penrose completely neglected to visit Matthew Quay, the boss of Pennsylvania politics, as was expected. Although Quay’s right-hand man, Bull Andrews, was outraged by this, Quay himself was intrigued and invited Penrose to dinner (Bowden, 52-53).

The Junior Partner

Penrose’s entrance into politics was a rather bold one, as he opted not to kowtow to the powerful Quay. Quay had ably served Governor Andrew Curtain during the War of the Rebellion as well as the Camerons, father and son Simon and J. Donald, and had in 1884 been elected Pennsylvania’s treasurer. His control over the taxpayer funds of the state made him the power, overshadowing Senator J. Donald Cameron, who had considerably less political skill than his wily father. Quay’s methods included graft, using the Pennsylvania State Treasury as a campaign fund and investing money from the treasury to grow it, practices that placed him at risk of going to prison. Penrose’s defiance, powerful intellect, and presence ultimately motivated Quay to take him in rather than to fight him. Although he had some disagreements with Quay on methods, for instance telling him at their introductory dinner, “Times are changing, Mr. Quay. Look at all the new inventions, all the new industries, and such things, springing up! They are going to be run by young men with new ideas and they’ll demand new political set-ups…It’s all plain to me” (Bowden, 57). Penrose ultimately became Quay’s junior partner in the machine, and when Quay was elected to the Senate, Penrose was his man in the state legislature to enforce his will. Quay and Penrose also employed the media to influence public opinion, holding controlling interests in numerous newspapers to grant them favorable coverage (Lukacs). With his rising power, he ultimately wanted to be Philadelphia’s mayor, and announced his run in 1894. However, there was a problem, and this was in Penrose’s lifestyle. Boies Penrose’s lifestyle was hedonistic; he ate what he wanted, drank what he wanted, and slept with ladies of the night. Given his wealth, anything he wanted he could and did pay for, and he was generally pretty open about the things he did, those things that others would opt to hide doing. This would result in Penrose’s only great political failure, as his opposition had managed to obtain a picture of him leaving a notorious brothel at dawn, forcing his withdrawal. This motivated him to be a bit more discreet in his dealings with women.

There were numerous ways he used power corruptly under Quay as well as on his own later. Penrose used the courts to protect lower-level individuals who had employed voter fraud and permitted corrupt schemes by his minions, yet Penrose himself never profited off his office and no evidence ever arose that his own election victories were due to voter fraud (Lukacs). He seemed to see it as necessary to allow his underlings some degree of corrupt behavior, as this was the way of machine politics in Pennsylvania, especially in Philadelphia. In 1897, Senator J. Donald Cameron was not running for another term, and although Penrose had a challenge from within the party from reformer John Wanamaker, he was elected. The next post will cover Penrose’s time as a senator until his death.

References

Bowden, R.D. (1937). Boies Penrose: symbol of an era. New York, NY: Greenberg.

Retrieved from

https://ia600200.us.archive.org/23/items/boiespenrosesymb00bowd/boiespenrosesymb00bowd.pdf

Lukacs, J. (1978). Big Grizzly. American Heritage, 29(6).

Retrieved from

https://www.americanheritage.com/big-grizzly

Noel, T. & Norman, C. (2002). A Pike’s Peak Partnership: The Penroses and the Tutts. University Press of Colorado.

Retrieved from

https://www.upcolorado.com/excerpts/9780870816895.pdf