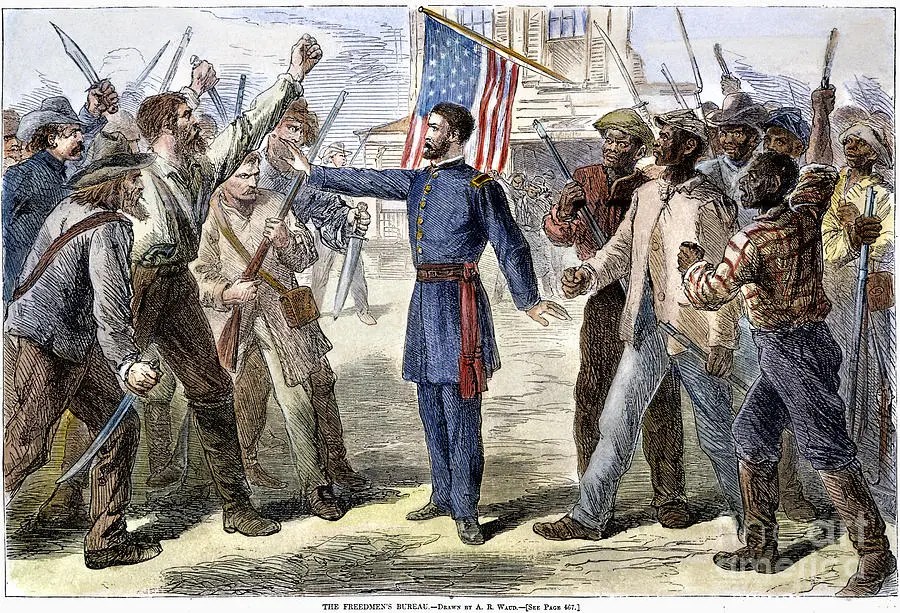

The War of the Rebellion had had a strong impact on the fortunes of the GOP, and this was particularly helped by their enactment of the 15th Amendment, which prohibited denial of suffrage based on race or color. Freedmen voted gratefully for Republicans and this resulted in the South having Republican representation to Congress for a time. However, resentment brewed among white Democrats, some who had been temporarily disenfranchised for their support of the Confederacy, and they sought to use means fair and foul, legal and illegal, to “redeem” the South. Complicating matters further for Republicans was the economic depression that came from the Panic of 1873 (the downturn lasted until 1879) and numerous corruption scandals in the Grant Administration including the New York custom house ring, the Star Route ring, and the Sanborn incident. Revelations of more scandals would follow this midterm. Historian James McPherson found the massive Democratic victories to be “due mainly to economic depression, political corruption, and the turbulence of Southern politics” (McAfee, 166). This is the typical story, but there is another factor that exists and it may have been the strongest of them all. Historian William Gillette, who studied the 1874 midterm extensively, concluded that the push for integrated schools factored above others in the Republicans’ 1874 loss, driving “Scalawags” or white Southerners who previously backed the GOP away, and that it had some impact in the North as well (McAfee, 167). Indeed, some Republicans attributed integrated schools as the issue that killed them in the election. President Ulysses S. Grant was among them (McAfee, 163).

How bad were the Republican losses? They lost 96 seats in the House, the largest single loss in the history of the Republican Party. As historian McAfee wrote, “As long as the Republican civil rights movement had not inconvenienced Northern whites, it moved forward. But the mixed-schools issue brought it to an insurmountable stone wall” (McAfee, 159). The Republicans suffered widespread net losses, with Kentucky and Nevada the only states in which they had a net gain of seats. Even in such stout Republican states as Illinois, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, Republican representatives found themselves in the minority of their House delegations. Losses in the South were quite present too, with them losing all representation in Arkansas and Georgia. Although campaigns of fraud, intimidation, and violence against black participation in voting played a role, whites who had previously supported Republicans (“scalawags”) switching to the Democrats played a role too in Republican losses in the South. Results were less terrible for the Republicans in the Senate, in which elections are every six years and they were far ahead of Democrats on Senate seats, but the Democrats did gain nine seats. They won against Republican or Liberal Republican incumbents in Connecticut and Missouri. Prominent Radical Republican Zachariah Chandler lost reelection to fellow Republican Isaac Christiancy. Democrats also succeeded retiring senators in Florida, Indiana, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. In the Texas election, Republicans were hardly in contention, with the major contest being between Democrats Samuel Maxey and James Throckmorton. Democrats only lost one seat, in California, but to Anti-Monopoly candidate Newton Booth, far from an ideal substitute for Senate Republicans.

Former President Andrew Johnson also scored a comeback by returning to the Senate in Tennessee, where support for Republicans was crumbling, but he wasn’t able to make much of it as he died mere months after being sworn in. This election, with the Democrats in control of the House and an increasingly embattled Grant Administration, signaled the doom of Reconstruction. Governor Adelbert Ames (R-Miss.), who would be forced to resign by the Democratic legislature, regarded the results thusly, “a revolution has taken place – by force of arms – and a race are disenfranchised – they are to be returned to a condition of serfdom – an era of second slavery” (Kato, 45-46). Whether or not Hayes had won, Reconstruction would have been brought to an end after the 1876 election given unified Democratic opposition to its continuance. Although Southern Republicans still remained, their presence would dwindle within the next 25 years rather than immediate disenfranchisement occurring. As historian C. Vann Woodward wrote, “It is perfectly true that Negroes were often coerced, defrauded, or intimidated, but they continued to vote in large parts of the South for more than two decades after Reconstruction” (Jenkins & Peck, 198). The last black Republican of the first generation of black politicians in Congress, George White of North Carolina, would leave office in 1901.

References

Jenkins, J.A. & Peck, J. (2021). Congress and the first civil rights era, 1861-1918. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Kato, D. (2016). Liberalizing lynching: building a new racialized state. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

McAfee, W.M. (1998). Religion, race, and Reconstruction: the public school in the politics of the 1870s. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.