The foremost general to politician known of the postwar period was of course President Ulysses S. Grant. However, there were others who had worthy performances in battle and were in politics. One of these men was John Alexander Logan (1826-1886) of Illinois.

Early Years

Politics was in Logan’s blood and had been on his mind from the time he was quite young. When he was a teenager, he wanted to be the “Congressman of the United States”! (Logan Museum). What’s more, his father had served in the Illinois General Assembly as a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. Before Logan entered politics, he served in the Mexican-American War, but did not see battle. He won his first political office at the age of 23 when he was elected clerk of Jackson County in 1849. Logan also attended the University of Louisville and graduated in 1851, serving as prosecutor for Illinois’ Third Judicial District. But a year later, he was elected to the Illinois General Assembly, and proved a tremendously talented public speaker. Much of Logan’s politics in the 1850s didn’t suggest his future, particularly his politics on race. Logan was against any free black settlement in Illinois, and sponsored a law that prohibited all free blacks from settling in the state, capping their time there at 10 days, with a $50 fine for any who stayed longer and indentured servitude for those who couldn’t pay (Morris Library). He also supported testimony laws, or laws that barred non-whites from testifying in court. In opposition to a proposal that permitted blacks to testify in court, he stated, “It was never intended that whites and blacks should stand in equal relation” (Logan Museum). He was also staunchly anti-abolitionist, as he regarded abolitionists as a force in American politics that were endangering national stability. In 1858, he was elected to Congress from a southern Illinois district (known as “Little Egypt” because of several towns named after Egyptian cities) which had sympathies with the South and, like him, were staunchly anti-abolitionist. However, Logan was also first and foremost unionist, just like the man he supported for president in 1860, Senator Stephen A. Douglas. He warned that “The election of Mr. Lincoln, deplorable as it may be, affords no justification or excuse for overthrowing the republic. [We] cannot stand silently by while the joint action of extremists are dragging us to ruin” (Joyner, 17). In August 1861, two months after the death of Douglas, Logan announced that he was resigning Congress to serve in the Union Army and encouraged his voters to do the same. Although Little Egypt was once a region that was in doubt as to its allegiance, they moved behind Logan and the Union. None other than Ulysses S. Grant credited Logan with keeping the region loyal to the United States, writing, “Logan went to his part of the State and gave his attention to raising troops. The very men who at first made it necessary to guard the roads in southern Illinois became the defenders of the Union. Logan entered the service himself as colonel of a regiment and rapidly rose to the rank of major-general. His district, which had promised at first to give much trouble to the government, filled every call made upon it for troops, without resorting to the draft. There was no call made when there were not more volunteers than were asked for. That congressional district stands credited at the War Department to-day with furnishing more men for the army than it was called on to supply” (Mr. Lincoln’s White House). After all, not all Midwestern Democrats proved unionists like Logan – Senator Jesse Bright of Indiana was expelled for recommending an arms dealer to Confederate President Jefferson Davis in a letter dated March 1, 1861 (U.S. Senate).

Military Service

Most generals who had been politicians beforehand were pretty bad at it. Benjamin Butler, Ambrose Burnside, and Nathaniel Banks were among the worst generals of the War of the Rebellion, with the latter being known by Confederate troops as “Commissary Banks” for his bad habit of leaving behind supplies while retreating. Logan, however, proved a natural commander and there’s a strong argument that he was the best of the politicians turned generals, leading the successful effort to capture Vicksburg and performing valiantly at Fort Donelson and Corinth. He became known as “Black Jack” Logan for his dark hair and eyes. Logan could have gone further in the military but for General William T. Sherman’s well-founded skepticism of generals who came from politics. It was, however, in the case of Logan unjustified, and he resented military careerists for the rest of his life over this perceived slight (Army Historical Foundation). Although he was approached to run for Congress in 1862, he was committed to ensuring the preservation of the Union before resuming his career.

A Political Transformation

The War of the Rebellion changed Logan. While he had once been a staunch Jacksonian who was opposed to abolitionism and President Lincoln, he was by 1864 a strong supporter of President Lincoln and came to support abolishing slavery. Was the change opportunistic or out of principle? The latter certainly seems true on the question of black rights. In 1860, Logan attended the Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina, and according to his biographer Byron Andrews, writing in 1884, he “had for the first time in his life had the opportunity to see the horrors of slavery. He witnessed the brutal scenes of the auction block, where men were sold for a price like cattle” and “the revolting inhumanities of the slave pen” (Dunphy). This does not appear to be the only factor. Logan himself told a group of Union veterans that witnessing the bravery of blacks during the War of the Rebellion had ended his prejudices (Morris Library). Instead of blaming the most devastating war in American history on abolitionists, he now squarely blamed it on the institution of slavery. In 1866, Logan was again elected to Congress, this time as a Republican. In Congress, he supported the 14th and 15th Amendments and argued that “I don’t care whether a man is black, red, blue, or white” on the question of whether they should have suffrage (Morris Library). Like his fellow Union general and former Democrat Benjamin Butler, he was one of the House managers for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, whose Reconstruction policies were highly lenient on the South and didn’t take into account the rights of freedmen.

Father of Memorial Day

As one of the most prominent and celebrated Union veterans, Logan served as the third Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, a powerful Union veterans organization that consistently pushed for more benefits for Union soldiers. On May 5, 1868, he proclaimed with General Order No. 11 a national day of remembrance for late and missing soldiers of the conflict in which their graves would be decorated to be held on May 30th, known as “Decoration Day”. This would come to be known as Memorial Day and adopted as a federal holiday in 1971.

Other Political Issues

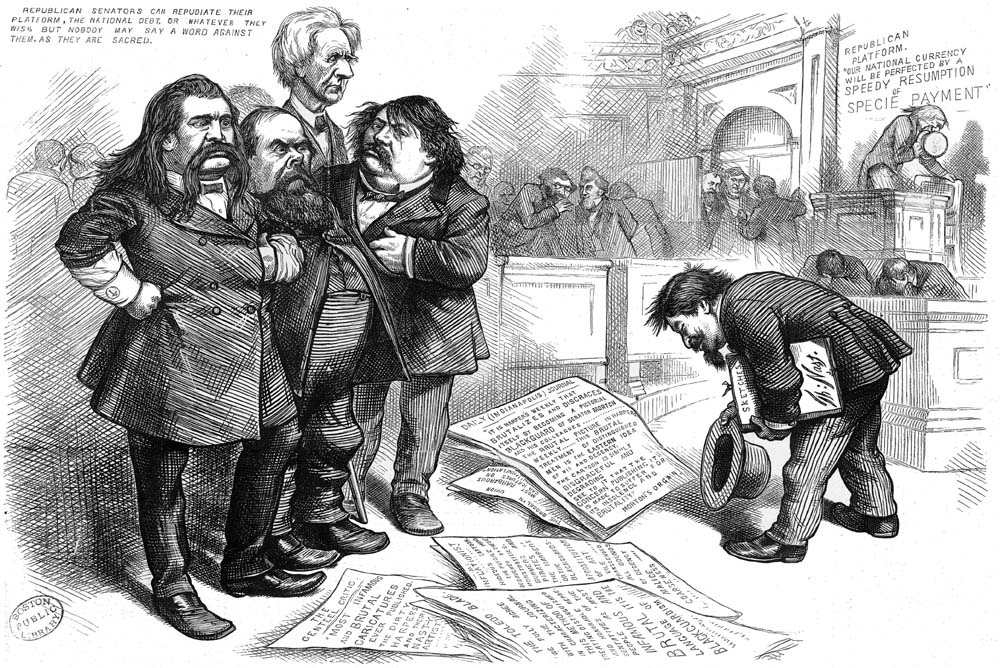

Logan was a partisan Republican, although not necessarily the most strongly ideological. In the conflict within the GOP on civil service, Logan was decidedly a Stalwart. Although Stalwartism can perhaps be considered the more “conservative” position in that time, it was in keeping with Logan’s old Jacksonian philosophy, as it had been President Jackson who had instituted the spoils system in the first place. Logan was also not a consistent vote for higher tariffs, voting to reduce in some categories. In 1874, he came out in support of the Inflation Act in an effort to stimulate the economy in the midst of the Panic of 1873, as did many Republicans in the Midwest. President Grant vetoed the bill, being convinced by Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton Fish and Senator Roscoe Conkling (R-N.Y.) to do so. In the cartoon below, Logan along with Senators Simon Cameron (R-Penn.), Oliver Morton (R-Ind.) and Matthew Carpenter (R-Wis.) are caricatured:

Republican Senators Logan, Oliver Morton (Ind.), Simon Cameron (Pa.), and Matthew Carpenter (Wis.) looking disapprovingly on Thomas Nast, portrayed as asking pardon for condemning their support for greenbacks.

Logan was also one of the foremost advocates in the Senate of expanding veterans’ pensions and also supported the Blair Education Bill in the 1880s aimed at increasing literacy, especially among Southern blacks. He was named in the Credit Mobilier Scandal but was cleared of wrongdoing by the investigating Poland Committee.

The 1880 Presidential Election

In 1880, Logan along with other Stalwarts supported the candidacy of former President Ulysses S. Grant for a third term, but they were undone when the supporters of Senators Blaine of Maine, Sherman of Ohio, and Edmunds of Vermont unified to nominate dark horse candidate Congressman James A. Garfield. Logan himself had interest in the presidency, but this would have to wait.

The 1884 Presidential Election and Future Prospects

In 1884, James G. Blaine, now regarding himself as a “Half-Breed”, provided balance to the GOP ticket by picking Midwestern Stalwart Logan. Logan was a solid choice as he had a strong personal following among Union veterans and black voters, due to his exemplary war record and strong support for civil rights respectively. The latter were facing increasing difficulties in having their vote counted in the South post-Reconstruction due to a combination of voter fraud, laws aimed at restricting the black vote, intimidation, and violence. The Blaine-Logan ticket lost in one of the narrowest presidential contests in American history, and Logan was bitter over the loss.

Logan continued his work in the Senate after this loss, and it was a real possibility that he would be running for president in 1888. He worked very hard on his duties in the Senate in the meantime, to the point that it compromised his immune system. By December of 1886 he developed acute rheumatism, and although it appeared he was recovering, his condition deteriorated over a period of close to two weeks, with an illness that caused fever, delirium, and lethargy, and died on December 26th (Beaverton Historical Society). Logan had worked himself to death, and he was far from the last senator to do so. His death reminds me of Stephen Douglas’s in 1861 in its untimeliness, and that his demise cut short a career that otherwise had the potential to lead to greater things. His DW-Nominate score was a 0.215 and had he been elected president, he would likely as had Benjamin Harrison made great efforts on behalf of Union veterans and black voters. One figure who mourned the loss of Logan was Frederick Douglass, who lauded him as “the dread of traitors, the defender of loyal soldiers, and the true friend of newly made citizens of the Republic. Much was predicated for our cause on this man’s future. But he, too, in the order of Providence, has laid off his armor” (Dunphy).

References

Dunphy, J.J. (2023, February 3). Logan repudiated his early racism, deserves stamp. The Telegraph.

Retrieved from

https://www.thetelegraph.com/opinion/article/john-logan-repudiated-early-racism-deserves-stamp-17761578.php

Expulsion Case of Jesse D. Bright of Indiana. U.S. Senate.

Retrieved from

https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/expulsion/040JesseBright_expulsion.htm

General John A. Logan, Memorial Day Founder. Army Historical Foundation.

Retrieved from

https://armyhistory.org/general-john-a-logan-memorial-day-founder/

John A. Logan – Death of the Illustrious Soldier and Statesman, Which Event Occurred At His Home In Washington December 26. Beaverton Historical Society.

Retrieved from

http://www.gladwinhistory.org/obits/Logan_John_A.html

John Alexander Logan, 1826-1886. SCRC Virtual Museum at Southern Illinois University’s Morris Library.

Retrieved from

https://scrcexhibits.omeka.net/exhibits/show/sihistory/poststatehood/logan#:~:text=During%20his%20first%20session%20in,Illinois%20longer%20than%20ten%20days.

Joyner, B. (2012). Dirty Work: The Political Life of John A. Logan. Eastern Illinois University.

Retrieved from

https://www.eiu.edu/historia/2012Joyner.pdf?itid=lk_inline_enhanced-template

Logan, John Alexander. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://voteview.com/person/5746/john-alexander-logan

Political Life. Logan Museum.

Retrieved from

https://loganmuseum.org/political-life/

The Generals and Admirals: John A. Logan (1826-1886). Mr. Lincoln’s White House.

Retrieved from

https://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/residents-visitors/the-generals-and-admirals/generals-admirals-john-logan-1826-1886/