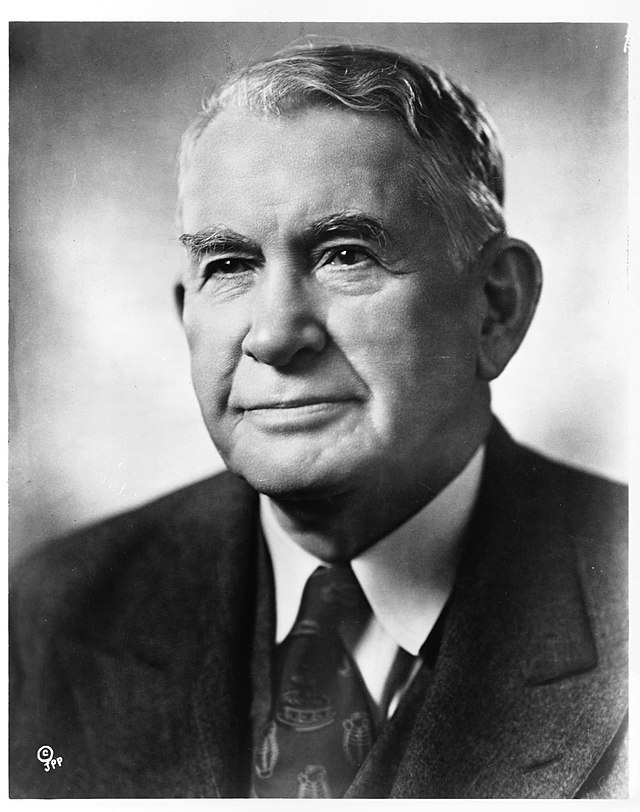

Barkley at the DNC

Barkley had as a senator become quite valuable for his oratory as well as advocacy for progressive positions, and this set him up for prime time. Barkley delivered the keynote address at the 1932 Democratic National Convention in which he condemned the Republican rule of the 1920s and called for the repeal of Prohibition, not because he personally disliked Prohibition, rather because the public wanted it. His speech was, to say the least, well received.

After FDR’s election, Barkley was one of the point men for pushing New Deal legislation, including the Agricultural Adjustment Act and the National Industrial Recovery Act, key parts of the New Deal. In 1934, Barkley, who had one of the most faithful records in supporting the first New Deal, went on the radio to defend it against the attacks of GOP chairman Henry Fletcher (Ghaelin, 76). He participated heavily in campaigning in the midterms, which saw one of the few times in which the president’s party gained rather than lost seats.

Barkley’s record as one of the most loyal Democrats in the Senate to Roosevelt was noticed, and he would again in 1936 give the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. Frustrated with the Supreme Court’s decisions striking down multiple New Deal laws, he rhetorically asked in this address, “Is the court beyond criticism? May it be regarded as too sacred to be disagreed with?” (Ghaelin, 76) This foreshadowed Barkley’s support of FDR’s “court packing plan”, following the lead of Majority Leader Joe Robinson (D-Ark.) in support. However, Robinson died on July 14, 1937, of a heart attack, which may have been in part attributable to the strain of pushing forward this plan. Roosevelt publicly declared neutrality for the following majority leader race, but made it clear that he supported Barkley in his letter to him in which he called on him to continue Robinson’s fight for the court packing plan, starting “My Dear Alben”. This letter became a subject of ridicule among his opponents with them derisively referring to him as “Dear Alben” to highlight his seemingly subordinate status, much to Barkley’s embarrassment (U.S. Senate). Barkley was up against Mississippi’s Pat Harrison, who although he had a history of progressive voting was growing more conservative and had opposed the court packing plan. Worse yet for FDR, Harrison if elected would leave his post as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and his successor would be Utah’s William H. King, who was of the party’s conservative wing and become quite antagonistic to the New Deal (Hill). Harrison had plenty of loyalists and had managed to sway future President Harry S. Truman to vote for him, but FDR rallied his loyalists as well. The deciding vote was that of Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi. Harrison despised Bilbo and the feeling was mutual, and Bilbo conditioned supporting him on Harrison personally asking him. When told of this, Harrison thought for a moment, and then replied, “You tell that son-of-a-bitch I wouldn’t speak to him if it meant the presidency of the United States!” (Hill)

Barkley as Majority Leader

Despite him having been favored by Roosevelt and initially backing the court packing plan, on July 22, 1937, he voted with 69 other senators to kill the plan, at that point such a vote was a simple acknowledgement of political reality. Barkley’s start as majority leader was not the easiest, as he had to contend with an anti-lynching bill introduced by Republicans and attempted to adjourn the Senate, but Republicans agreed to shelve the bill after Barkley promised that it would be considered in the next session (Ghaelian, 78). Although Barkley was true to his word and pushed for anti-lynching legislation, the measure fell to defeat. He also in August 1937 lost on a parliamentary motion by Minority Leader Charles McNary (R-Ore.) to recess, concluding the first session of the 75th Congress (U.S. Senate). However, he won over his Democratic colleagues and proved easier to get along with than his predecessor, who could be a bully and tough as nails. Rather than intimidation or coercion, he used persuasion to move along legislation plus many an amusing story, like another man who was born in Kentucky…Abraham Lincoln. As Barkley himself said, “A good story is like a fine Kentucky bourbon. It improves with age and, if you don’t use it too much, it will never hurt anyone” (U.S. Senate). Barkley’s talent for persuasion as well as negotiation made him quite valuable to FDR and the Democrats.

The 1938 Democratic Primary & Controversies

In 1938, Barkley drew a significant challenger in the primary in Governor A.B. “Happy” Chandler. Chandler was to Barkley’s right, being less supportive of the New Deal, and Roosevelt went to Kentucky to campaign for Barkley. During the campaign, allegations over the use of Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers to boost Barkley arose. In Kentucky, there were 72,000 people employed for numerous projects, great and small, and would ultimately over eight years employ 8.5 million people at a cost of $11 billion (Myers, 31-32). On May 27, 1938, Chandler’s campaign manager alleged in an open letter that “every federal relief agency in Kentucky is frankly and brazenly operating on a political basis”, a claim contested by Kentucky’s WPA director George Goodman (Myers, 35). However, Chandler’s campaign wasn’t above using such tactics. Indeed, state employees were being used to try to influence voters for Chandler (Myers, 36). This race was a nailbiter, but Barkley prevailed. The truth of the matter was hit upon after an investigation by journalist Thomas L. Stokes that uncovered that federal WPA employees were working extensively to intervene on behalf of Barkley while Kentucky state employees were doing so for Chandler (Myers, 41). This resulted in the passage of the Hatch Act in 1939, which prohibited the use of civil service employees for certain political activities, with the exceptions of the president and vice president.

Barkley was a Wilsonian on foreign policy, as was Roosevelt, and he successfully pushed the Senate into passing the repeal of the arms embargo in 1939, the peacetime draft in 1940, Lend-Lease in 1941, and lifting the ban on U.S. ships carrying goods to belligerent ports.

A Break with Roosevelt

Contrary to the perception that the United States was politically united during World War II (they were on the war effort), the 78th Congress was the least friendly Congress President Roosevelt faced. Barkley in this Congress in one debate that required overcoming a filibuster ordered the arrests of senators staying absent to force them to vote, including his friend Kenneth McKellar (D-Tenn.). McKellar, a man known for his hot temper, was so resentful over this incident that he denounced him on the floor of the Senate, withdrawing his recommendation of Barkley on the Supreme Court, and after refusing to speak to him (Hill). FDR’s legislative demands were thus wearing on his legislative wheelhorse. Another contentious subject was taxation to pay for the war. President Roosevelt had asked for a $10.5 billion tax increase to pay for the war effort and restrain inflation, but the bill that was passed by the House, spearheaded by House Ways and Means Committee chairman Robert Doughton (D-N.C.) included only $2.1 billion in increases (Glass). The previous revenue bill, the Revenue Act of 1942, had been highly redistributive. Although Barkley may have wished to deliver a more substantive bill to the president, he figured this was the best bill he could deliver. Thus, he agreed to the legislation (U.S. Senate). Roosevelt in turn vetoed the bill. He, however, did not just veto it, he ripped on Congress in his veto message, denouncing the measure as a “tax relief bill providing relief not for the needy but for the greedy” and finished with “The responsibility of the Congress of the United States is to supply the Government of the United States as a whole with adequate revenue for wartime needs, to provide fiscal support for the stabilization program, to hold firm against the tide of special privileges, and to achieve real simplicity for millions of small income taxpayers. In the interest of strengthening the home front, in the interest of speeding the day of victory, I urge the earliest possible action” (Glass). This inflamed the legislators and increased support for the bill. Barkley responded by resigning in protest, denouncing Roosevelt’s veto and message as “a calculated and deliberate assault upon the legislative integrity of every member of Congress. My resignation will be tendered and my services terminated. If the Congress…has any self-respect left, it will override the veto” (U.S. Senate). Barkley, previously known as FDR’s man in the Senate, had wowed his colleagues by demonstrating independence. McKellar responded in delight, “I forgive him everything! I forgive him everything he’s ever done!” (Hill) The veto was overridden, and Senate Democrats united the next day to unanimously elect him majority leader. Senator Elbert Thomas (D-Utah) said to journalist Allen Drury of the change in perception surrounding Barkley, “the impression was given…that he spoke to us for the President. Now that he has been unanimously elected, he speaks for us to the President” (U.S. Senate). Roosevelt hastily backtracked and apologized to Barkley, endorsing his reelection in 1944. However, Barkley would not be selected for vice president, an outcome you already certainly knew otherwise history would tell of a “President Barkley”.

A Change on Civil Rights

Although in the House, Barkley had been an opponent of civil rights legislation, he was a strong supporter, including supporting retaining the Fair Employment Practices Committee, for anti-lynching legislation, and for anti-poll tax legislation. This change closely coincided with the majority of the black vote going to Democrats. His change on this subject, an even more dramatic change than seen in his Arizona colleague Carl Hayden, was demonstrative of the Democratic Party having a solid degree of political motivation for backing civil rights legislation. To be fair, there was certainly a good deal of political motive in opposing such legislation, as undoubtedly it was unpopular in Barkley’s 1st district.

Barkley and Truman

If Barkley had a fairly good relationship with FDR despite the Revenue Act bump in the road, he had a better one with his successor, Harry S. Truman. The 1946 election had produced a Republican majority in the House and Senate for the first time since the Hoover Administration, and, like Truman, Barkley battled the domestic prerogatives of the 80th Congress while assisting Truman in passing foreign policy priorities. Americans for Democratic Action graded him perfect scores in 1947 and 1948 for defending the liberal position on key issues, including opposing the Taft-Hartley Act and opposing Republican-backed tax reduction legislation. In 1948, Truman, who had no vice president while finishing FDR’s fourth term, selected his most valuable Senate ally as his running mate. The 1948 election, which produced one of the more notable “upsets” in U.S. history, made Barkley the third vice president from Kentucky.

As VP, or as his grandson called him, “The Veep”, Barkley did his best in his function as the Senate president to help the fractured Democratic majority, but things weren’t the same without him in the driver’s seat as majority leader, and his successor, Scott Lucas of Illinois, struggled mightily to unify his divided party. In 1949, Barkley made a favorable ruling on Majority Leader Scott Lucas’s (D-Ill.) rule change to make ending debate easier. A major issue coloring that debate so to speak was the matter of civil rights, so Senator Richard Russell (D-Ga.), the leader of the Southern Democrats of the Senate, appealed, and the Senate sided with Russell 46-41. Barkley also hit the campaign trail for Democrats in both 1950 and 1952, but with the unpopularity of President Truman Democrats suffered losses, and both times their majority leaders, Scott Lucas of Illinois and Ernest McFarland of Arizona, lost reelection too. In 1952, Barkley wanted to run for president, but he bowed out after many in the party regarded him as too old at 75. How quaint!

In 1954, Barkley, now 77 years old, was up for another go at the Senate. The Democratic Party was in luck that he was up to go again, as Republican incumbent John Sherman Cooper, who was one of the most liberal Republicans in the Senate, was proving quite popular. The campaign generally revolved around the idea that Barkley was too old to run again, but he dispelled this notion by campaigning with a vigor that spoke of a considerably younger man, resuming his “Iron Man” campaign style. Barkley defeated Cooper by nine points. He then supported President Eisenhower’s nomination of Cooper as Ambassador to India and Nepal.

The Best Death in the History of American Politics?

It turned out that there was something to what the Republicans were saying about Barkley and age. On April 30, 1956, Barkley was delivering a speech at the Washington and Lee Mock Convention and referring to his willingness to sit in the back row of the Senate despite his 40 years in public office declared, “I’m glad to sit in the back row, for I would rather be a servant in the House of the Lord than to sit in the seats of the mighty” (U.S. Senate). Upon a standing ovation for his words, Barkley then collapsed, dead from a heart attack at 78. However, something that was not so great of a revelation after his death is that despite Barkley being such a proponent of more government programs through the New Deal and the Fair Deal, he had not paid income taxes for years (Hill). His death opened the door for Cooper’s return to the Senate, and indeed in the 1956 special election he won the election to finish his term.

Barkley was a figure who could be quite liberal by inclination and also showed willingness to change in how he voted, and that change was generally in a liberal direction. He was also capable of compromise and defiance if he felt the Senate’s prerogatives were being trodden on. He also serves as quite a contrast in many ways to politics as we know them now. As a Kentucky liberal his philosophy of government was favored by the state’s voters for at least most of his time in office. That Kentucky would today be represented in the Senate by Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul and that they would win reelection multiple times are developments that frankly couldn’t have been foreseen in Barkley’s lifetime. The Republicans that were elected to the Senate after Barkley’s passing, Cooper and Thruston Morton, were moderate in inclination, with Cooper siding more with liberals and Morton more with conservatives.

References

Congressional Supplement. (1948, July). Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Ghaelian, J. (2008). Alben W. Barkley: Harry S. Truman’s Unexpected Political Asset. Kaleidoscope, 7(15).

Retrieved from

Glass, A. (2018, February 24). House overrides FDR’s Revenue Act veto, Feb. 24, 1944. Politico.

Retrieved from

https://www.politico.com/story/2018/02/24/house-overrides-fdrs-revenue-act-veto-feb-24-1944-421684

Harrison, L.H. & Klotter, J.C. (1997). A new history of Kentucky. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky.

Hill, R. Alben W. Barkley of Kentucky. The Knoxville Focus.

Retrieved from

Myers, R.M. (2018, May). “To prevent pernicious political activities”: the 1938 Kentucky Democratic primary and the Hatch Act of 1939. College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 169.

Retrieved from

Report Card for 80th Congress. (1947). Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

Senate Leaders: Alben Barkley. U.S. Senate.

Retrieved from

https://www.senate.gov/about/origins-foundations/parties-leadership/barkley-alben.htm