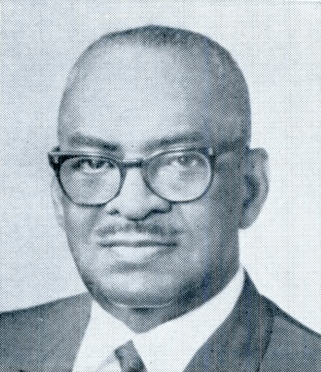

Illinois’ first district, based in a majority black area of Chicago, was the first in the 20th century to elect a black man to Congress. The first one was Oscar De Priest, a Republican who although not ultra-conservative, was opposed to the New Deal broadly. De Priest’s politics, and those of the GOP, fell out of favor with a majority of black voters during the Great Depression and he lost reelection in 1934. De Priest had been part of the Republican machine in Chicago, and it was a machine from which several black politicians traced their political start, including De Priest’s successor Arthur W. Mitchell as well as his protégé, William Levi Dawson (1886-1970).

Dawson had been born and raised in Georgia, where he attended segregated schools. At the age of 19, he fled the Deep South after an altercation with a white man and his family followed soon after his father also had one (Manning, 2003, 3). A lawyer by profession, Dawson became active in the Chicago Republican Party in the 1920s and his political career kicked off when in 1930 he was elected to the Illinois Republican Central Committee, and in 1933 he was elected to the Chicago City Council, representing the 2nd ward. By inclination, he was already on the road to liberalism, being a New Deal Republican. Dawson proved an effective political organizer, employing patronage and precinct workers, creating a political machine of his own that spanned up to five wards (WTTW).

In 1938, Dawson ran for Congress, giving his old mentor Democrat Arthur W. Mitchell a substantive challenge. The next year, he decided to leave the GOP and align himself with Democratic Mayor Ed Kelly. Fortunately for him, by 1942, Mitchell, who was not a particularly popular representative, had crossed the Chicago machine of Mayor Ed Kelly, who had not appreciated his lawsuit against a railroad company based in Chicago for racial discrimination and it was known to Mitchell that Kelly would not back him for another term (Hill). Instead, Kelly’s backing went to Dawson, who won election to Congress in 1942.

Dawson was typically known as a man who wasn’t much of a national boat-rocker, but he from time to time he was outspoken on a civil rights matter, such as opposing the construction of a segregated VA hospital in 1951. Additionally, he delivered that year a notable speech against the proposed Winstead Amendment, which The Chicago Defender credited for its defeat, that if adopted would have allowed whites to opt out of integrated units in the military thereby undermining desegregation, stating, “There is but one God and there is but one race of men all made in the image of God. I did not make myself black any more than you made yourselves white, and God did not curse me when he made me black anymore than he cursed you when he made you white” (Manning, 2009). Dawson’s work on civil rights tended to be more behind-the-scenes. For instance, an article in the July 1972 edition of Ebony magazine written by Doris E. Saunders credited Dawson with playing a significant role in blocking Jimmy Byrnes from the vice-presidential nomination. The South Carolinian Byrnes had in his long career worn many hats, and one of them was as Roosevelt’s right-hand man on domestic issues. Another, and this was consistent throughout, was as a segregationist. Dawson, although officially only a representative from Illinois’ 1st district, was the only representative in Congress in 1944 who was black and thus his views would be influential for black people across the nation. He made it clear to FDR that he would not accept a candidate that was unacceptable for the black voter, and the Democratic Party of 1944, especially when up against Thomas E. Dewey and a Republican Party with a pro-civil rights platform, needed to get the majority of black votes. Dawson, at the behest of Mayor Ed Kelly, met with Byrnes for three hours at the Blackstone Hotel, and emerged concluding that Byrnes was indeed unacceptable and made it clear this was so (Saunders, 49-50). Ultimately, Senator Harry S. Truman of Missouri was picked as a compromise nominee. In 1949, Dawson became the first black chairman of a Congressional committee, heading the Committee on Government Operations. Starting that year, he led voter registration drives in multiple Southern states (Manning, 2003, 4).

Although Dawson was a rather quiet success in Congress, this didn’t please everyone. Black radicals Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton regarded him as a “tool of the downtown white Democratic power structure” (Manning, 2003, 5-6). Dawson was also criticized by the militant black publication The Chicago Defender. He was characterized as “non-committal, evasive, and seldom takes an outspoken stand on anything. Bill Dawson is, by all odds, ultra-conservative” (WTTW). Despite these views, Dawson repeatedly received high scores from the liberal Americans for Democratic Action. From 1947 to 1964, for instance, he opposed the ADA position only three times. Dawson’s DW-Nominate score has him at a -0.527. For reference, Bernie Sanders’ score is a -0.539. Some analyses of his career have pointed to a more complex picture than that of Carmichael and Hamilton, such as Charles Branham’s 1981 analysis in which he writes, “Rather than being “co-opted” by the white political machine, Dawson embraced the historically dualistic tradition of black political culture in Chicago. His career was consonant with a tradition of clientage, patronage and dependence which coexisted, sometimes uncomfortably, with the racially self-conscious heritage of social welfare, civil rights, and the maintenance and expansion of the race’s representation” (Manning, 2003, 10). In 1958, Dawson faced a notable challenger in civil rights activist Dr. T.R.M. Howard, but his political machine was sufficiently robust and voters sufficiently Democratic to easily fend him off. By this time, Dawson had formed an alliance with Mayor Richard Daley, whose machine placed Chicago in the Democratic column for good.

Although Dawson voted for all the major civil rights laws of the 1950s and 1960s, he wasn’t really at the forefront of the civil rights movement, focusing more on maintaining power in Congress and in his district. In 1960, he was of significant help to JFK in rallying the black vote in Chicago for him. Illinois was, with Texas, the swing states that Kennedy needed to win the election. In 1961, Dawson declined an offer from him to be postmaster general, preferring to remain at his perch in Congress. Had he accepted and been confirmed, he would have been the first black cabinet officer in American history. As would be expected, Dawson was a strong supporter of both JFK’s New Frontier and LBJ’s Great Society programs. In his later years, he was in poor health and in his last term in Congress he had cancer. However, the proximate cause of his death on November 9, 1970, at Chicago’s VA hospital, was pneumonia.

References

ADA Voting Records. Americans for Democratic Action.

Retrieved from

https://adaction.org/ada-voting-records/

Dawson, William Levi. Voteview.

Retrieved from

https://www.voteview.com/person/2433/william-levi-dawson

Hill, R. Mitchell v. United States, et. al. The Knoxville Focus.

Retrieved from

https://www.knoxfocus.com/archives/this-weeks-focus/mitchell-v-united-states-et-al-arthur-w-mitchell-of-illinois/

Manning, C.E. (2003). The ties that bind: The congressional career of William L. Dawson and the limits of black electoral power, 1942-1970. Northwestern University.

Retrieved from

https://www.proquest.com/openview/e08f22e061030216b31ce62828015d41/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Manning, C.E. (2009). “God Didn’t Curse Me When He Made Me Black”. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 102(1).

Retrieved from

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27740147

Power, Politics, & Pride: Dawson’s Black Machine. WTTW.

Retrieved from

https://interactive.wttw.com/dusable-to-obama/dawsons-black-machine

Rep. William L. Dawson Dies; Served Chicago Area Since ’42. (1970, November 10). The New York Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/11/10/archives/rep-william-l-dawson-dies-served-chicago-area-since-42-first-negro.html

Saunders, D.E. (1972, July). The Day Dawson Saved America from a Racist President. Ebony Magazine.

Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/books?id=M9oDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA42&lpg=PA42&dq

Interesting biographical summary, Mike; while the Southern black shift to the national Democrats was due to race after the Johnson Administration took credit for the CRA 1964 and the VRA, the Northern black vote shift was… noticeably different. Clearly economics seemed to trump race sometimes, in part since Northern blacks were, for starters, more privileged than their Southern counterparts. While De Priest was a vocal activist for civil rights, the NAACP continuously lamented of his opposition to liberal government economic initiatives, if I remember reading correctly. And even while De Priest’s liberal Democratic successor Mitchell comparably paid lip service to civil rights, introducing a weak anti-lynching bill, the seat didn’t return to its old Republican stronghold.

Speaking of Dawson’s activism in 1944, it appears that several factors, not just that, saved the national Democrats from losing the black vote. The pro-civil rights faction prevented excessive Southern influence, but also, I would argue that… Southern Democrats blocking anti-lynching legislation in the Senate in the 1930s-(early) 40s was significant too in this regard. Why? Because if any of the major anti-lynching bills, aka the Costigan-Wagner, Gavagan-Wagner-Van Nuys, and/or Gavagan-Fish Acts, passed the Senate and made it to the presidential desk, FDR would almost certainly have vetoed them (his remarks in 1935 to NAACP leader Walter White weren’t… particularly receptive to civil rights activists), resulting in Northern black people criticizing the Democrats nationally as anti-civil rights, and thus flocking back to the GOP. Because those anti-lynching bills were blocked in the Senate, FDR was “saved” from having to drastically alienate either the Northern black or Southern white bloc of the New Deal Coalition. And of course, since the minority Senate GOP ultimately voted against cloture on the Wagner-Van Nuys Act in the late January of 1938, black leaders didn’t see the GOP as any more helpful than the Democrats, with Roy Wilkins accusing a “conspiracy” whereby the Republicans allegedly never wanted the anti-lynching bill to pass at all. (of course, it was almost certainly that the Senate GOP viewed the cloture vote as hopeless anyways and thus had no motivation, knowing the motion would fail with or without their measly 17 votes)

Oh yeah, the careful balancing of the desires of the New Deal Coalition’s separate blocs and its ultimate internal rifts fracturing it into pieces by the 1970s-80s seems to parallel the current Democratic Party woes of trying to appease both the Jewish and Arab vote as the Israel-Hamas War is a major issue in the election campaign. Personally, I’m almost inclined to laugh my head off over the fact that modern neo-Marxist leftists were ignorant enough to stereotypically think of various ethnic minorities as a conglomerate, united monolithic bloc, and spend years building their “progressive” coalition only to be about to miserably find out, the real hard way, that their fantasies are hitting an inevitable brick wall. Not that the upcoming election result next year will ultimately prove to be for the benefit of America by any stretch, and yet there will still be some popcorn and fun on the side of mainstream right-leaning folks watching the obnoxious neo-Marxist agitators fall apart in their own bunkum.