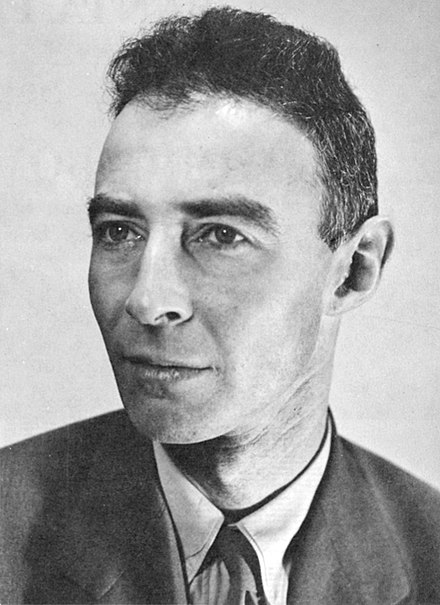

Given the release of what just might be film director Christopher Nolan’s magnum opus, Oppenheimer, it is now a good time to take a look at him politically. J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967) is foremost known in the public consciousness, and rightly so, for being the “father of the Atomic Bomb”. Also perhaps known is that in 1954, he was stripped of his security clearance after a contentious security hearing before the Atomic Energy Commission. Oppenheimer is often portrayed sympathetically on this, and indeed the U.S. government last year posthumously restored his security clearance. Journalist Kai Bird and historian Martin Sherwin concluded that he was not a communist in their 2005 biography of him, American Prometheus, for which the film is based on, holding that he “was branded a security risk at the height of anticommunist hysteria in 1954” and that he merely had “hazy and vague connections to the Communist Party in the 1930s – loose interactions consistent with the activities of contemporary progressives” (Radosh, 2012). This fits completely with what Oppenheimer said about himself, and indeed many biographers choose to take him at his word. However, the real story on him is a bit different.

There is no doubt that Oppenheimer was a man of the left, and those he closely associated with were communists, including his wife, his brother Frank (who admitted it in 1949), and his friends, one of whom was French literature professor Haakon Chevalier. He himself admitted to being a “fellow traveler” although he denied having been a member of the Communist Party at his security clearance hearing in 1954. However, was he a communist or, worse, a spy?

Affiliation with the CPUSA: Late 1930s-1942

Historians John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr (2012) concluded based on available evidence that it “convincingly indicates that Robert Oppenheimer joined the CPUSA in the late 1930s. Exactly when he joined is not clear. Certainly by 1939 he was active in the secret Communist faculty unit at the University of California, Berkeley, remained so in 1940 and into 1941, and actively participated in public Party-related activity through the end of 1941. A corollary of this evidence is that Oppenheimer repeatedly perjured himself on government security forms he signed, in statements to security officials and his colleagues, and under oath in testimony to the AEC.” These activities included writing pamphlets. One of these, according to physicist Philip Morrison, a student of Oppenheimer’s and a young communist, was defending the USSR’s invasion of Finland and another one was attacking FDR as a “war monger” and a “reactionary” for modest measures to mobilize for war (Haynes and Klehr, 2012). Around the time of his recruitment to the Manhattan Project in 1942, he had dropped out of the CPUSA. However, there is a more disturbing charge about him…that he passed on intelligence to the Soviets.

Soviet Spy?

The Case For

In 1994, Pavel Sudoplatov, who oversaw Soviet espionage for the atomic bomb, claimed in his book Special Tasks that Oppenheimer had provided the Soviets with intelligence reports on the development of the atomic bomb (Romerstein & Breindel, 274). This was not the first time Sudoplatov had mentioned Oppenheimer in connection with espionage. In 1982, he appealed to Soviet leader Yuri Andropov for his rehabilitation (he was on the outs due to his connections with Lavrenty Beria), claiming that he had “rendered considerable help to our scientists by giving them the latest materials on atom bomb research, obtained from such sources as the famous nuclear physicists R. Oppenheimer, E. Fermi, K. Fuchs, and others” (Romerstein & Breindel, 275). There is also a letter from Boris Merkulov to Lavrenty Beria published in Sacred Secrets by Jerrold and Leona Schechter that indicates that Oppenheimer informed the USSR about the start of the Manhattan Project and that Communist Party members should distance themselves from atomic scientists so as to lessen the risk of attention being drawn to their extensive intelligence network in the United States.

The Case Against

In 1995, the FBI reviewed its files and, in the process, cleared Oppenheimer of espionage. At the time of his book’s publishing, Sudoplatov was 87 years old, so it is possible that he mixed up some details or even lied about his record in his appeal to Andropov. Another issue is that the GRU (Soviet military intelligence) and the NKVD were trying to recruit Oppenheimer in 1944, which begs the question, why were they trying to recruit him if he was already engaging in espionage for them? Additionally, there were already Soviet agents at Los Alamos who were confirmed to have given atomic bomb secrets to the Soviets in Klaus Fuchs and Ted Hall (Schechter et. al.). Additionally, it is not confirmed that the Merkulov letter to Beria is genuine. There is also no documentation as to how the Schechters (who worked with Sudoplatov in his book) came across this document. If authentic, it proves that Oppenheimer provided intelligence to the USSR, but as it is not confirmed, we must take it with a grain of salt.

Overall

The weight of evidence reflects the conclusions of Haynes and Klehr, including their view that Oppenheimer was evasive due to a sense of pride, although it is an interesting detail that Sudoplatov had in 1982 claimed all these scientists, including Oppenheimer, were passing on information to the Soviets. At least one of the people he mentioned, Fuchs, was proven to have been an agent. Was Sudoplatov embellishing in 1982 to Andropov in his efforts to be rehabilitated and was his memory off by the time of Special Tasks given his advanced age? But what is clear is that Oppenheimer was a communist in the 1930s and up until his recruitment to the Manhattan Project. Notably, after World War II, Oppenheimer appeared to have a bit of a change in philosophy, as Haynes and Klehr (2012) write, “Whatever the initial reason for Oppenheimer’s dropping out of the CPUSA in 1942, it seems clear that by 1946 he was a firm supporter of the developing Cold War liberalism that would dominate the Truman administration and the Democratic Party in the late 1940s, ’50s, and into the mid ’60s.”

References

Haynes, J.E. & Klehr, H. (2012, February 11). J. Robert Oppenheimer: A Spy? No. But a Communist Once? Yes. Washington Decoded.

Retrieved from

https://www.washingtondecoded.com/site/2012/02/jro.html

Letter from Boris Merkulov (USSR People’s Commissar for State Security) to Lavrenty Beria (USSR People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs), 2 October 1944.

Retrieved from

Radosh, R. (2012, February 15). Was the Father of the A-Bomb a Communist and Soviet Spy? Hudson Institute.

Retrieved from

https://www.hudson.org/domestic-policy/was-the-father-of-the-a-bomb-a-communist-and-soviet-spy-

Radosh, R. (2021, May 6). Secrets and Lies. Law & Liberty.

Retrieved from

https://lawliberty.org/book-review/secrets-and-lies/

Risen, J. (1995, May 2). FBI Clears Top Physicists of Passing Weapons: Allegations in ex-KGB officer’s book that Oppenheimer, Bohr, Fermi and Szilard had given postwar aid to Soviets provoked outrage. Los Angeles Times.

Retrieved from

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-05-02-mn-61373-story.html

Romerstein, H. & Breindel, E. (2001). The Venona secrets: exposing Soviet espionage and America’s traitors. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing.

Schechter, J., Schechter L., Herken, G., & Peake, H. Was Oppenheimer a Soviet Spy? A Roundtable Discussion. Wilson Center.

Retrieved from

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/was-oppenheimer-soviet-spy-roundtable-discussion